There has been no shortage of oil price talk in recent months – and no shortage of oil for that matter. Every week it seems a new low cost record is broken, and whereas a barrel of Brent last year clocked in at over $100, you can take one home today for approximately $50. Consumers meanwhile, are glad of the pennies saved at the pump and some countries have responded to this new low cost environment by recouping some of the money lost to subsidies in years passed. However, for the members of OPEC, whose finances rely on black gold, the storm clouds show no signs of parting, and pressure is mounting on recession-hit Venezuela to rethink its reliance on oil and its restrictive currency controls.

For too long, Venezuela has allowed oil prices to dictate its success, and with inflation running at record-breaking heights and fiscal debts mounting (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), President Nicolás Maduro must get a firm grasp on the country’s currency controls before basic goods are rationed and rioting takes over. Diversification is the name of the long game, but many of the more immediate concerns can be remedied by targeted reforms.

An oil producer since 1914, the realisation in 2012 that Venezuela was home to the world’s largest reserves led many to wrongly assume that the country’s success was assured for the near term. The period since, however, has shown that such distinctions do not necessarily guarantee growth, and the country’s recent macroeconomic indicators make for uncomfortable reading.

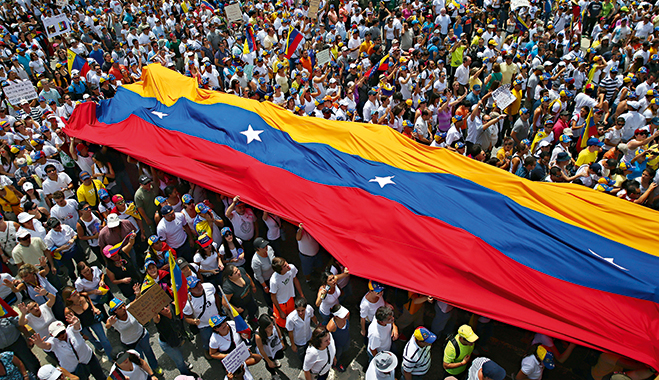

With many people of the opinion that Maduro’s ruling administration is beyond help, thousands have called for Chavez’s successor to step down and for a new government to take charge

“The freefall in oil prices, as well as its implications, will be Venezuela’s biggest challenge for this year”, says Ricard Torné, Senior Economist at FocusEconomics. “Taking into account that the breakeven oil price for Venezuela is well above $100 per barrel and that the price per barrel is now below $40, government revenues are going to fall dramatically this year. This situation will likely prompt the government to cut spending on social programmes and/or to reduce the fuel subsidy, thereby eroding President Nicolás Maduro’s political base. The parliamentary elections scheduled for Q4 2015 will be a crucial test to assess the popularity of Maduro’s administration.”

Venezuela down

The central bank unleashed findings in the final days of 2014, showing that the economy had sunk 2.3 percent in the third quarter and capping a dismal year in which the country had already contracted 4.8 and 4.9 percent in the first and second quarter respectively. To add insult to injury, inflation in the 12 months to November clocked in at a record 63.6 percent – the highest in Latin America. “In 2014, we again faced the script of destabilisation and violence”, says Maduro. However, for anyone taking a closer look at the country and its workings, it’s clear that the issues are rooted in Venezuela’s failure to improve upon inadequate currency controls, diversify its economic make up and manage inflation.

The dismal economic showing triggered widespread civil unrest last year, and when in February students in Tachiras and Merida took to the streets for greater reassurances about their future prospects, thousands across the country echoed their concerns. What initially started as a condemnation of inadequate campus security later turned into a protest against spiralling crime rates and an inability to keep a lid on inflation. With many people of the opinion that Maduro’s ruling administration is beyond help, thousands have called for Chavez’s successor to step down and for a new government to take charge.

Spearheaded by a dissatisfied Venezuelan middle-class, Maduro’s critics were soon after opposed by his supporters, and the violence that followed made for some of last year’s more disturbing pictures. With those opposed-to arguing that corruption was rife and that Venezuela amounted to little more than a failed state, those-for were willing to fight for their beliefs; a fact that brought with it terrible consequences. Only when the tanks rolled in did the situation subside, though not before 43 deaths and hundreds of arrests, failing to instil confidence in anyone that the country’s circumstances would change.

One survey carried out by Pew Research in September of last year found that more than three out of every four Venezuelan’s – that’s 77 percent – believe the country is headed in the wrong direction, yet the Caracas-born president enjoys near enough the same level of support as his opposition. A total of 57 percent believe Maduro has a bad influence on the country’s direction, whereas 52 percent believe Henrique Capriles’s opposition party has the same effect, which shows a lack of trust in the political system itself – to which 55 percent of respondents attest.

One year on from the protests and it appears that the issues that dogged Venezuela back then are little – if at all – changed. At the tail end of January, thousands gathered again in the country’s capital to highlight its less-than-effective government policies and worsening economic climate. The inflation rate is higher than it was a year ago, crime is still on the rise, and people are finding it increasingly difficult to acquire even basic goods, leaving anti-government protestors to once again urge Maduro to step down.

With empty pots in-hand, protestors illustrated that staple foods and basic medicines were becoming increasingly hard to come by. Pictures of empty shelves circulated online, as did snaking shop queues, and eventually the military was called upon to keep the commotion to a minimum. However, the president has sought to reassure citizens that the shortages were part of “an economic war” being waged against his government, and even accused four supermarket chains of hoarding and smuggling goods.

Pushing forward reforms

These events are an indication of the many hurdles Maduro must first clear if he is to win the approval of the masses. Few contest that Venezuela is in dire straits and all are agreed that changes must come fast if the country is to escape collapse. And while the president pledged in December to act swiftly and upend the country’s restrictive currency controls, reforms have not come fast in the past.

Reforming the country’s three-tier foreign exchange system constitutes perhaps the biggest part of a six-month plan to breathe fresh life into the economy this coming year, as the government looks to reduce inflation, boost international reserves and more closely manage costs. Critics, meanwhile, have launched an assault on Maduro’s history of inaction on the issue, and believe the unspecific nature of the claim is proof that the president’s pledge will come to nothing. There is reason to believe that this time could be different, however, in that falling oil pressures have piled extra stress on Maduro’s government to instil change, and quickly.

Inasmuch as 95 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings depend on oil, and the resource, combined with gas, accounts for 25 percent of national GDP: the success of the economy is inextricably tied to the price of oil. Without high prices, the country cannot afford to keep even basic public services afloat, and reports of inadequate hospital supplies are widespread. Add to that the local currency’s depreciation and a byzantine exchange system, and Venezuela’s current situation looks untenable for the near future.

“The government should embark on reforming the current three-tiered exchange rate system, ease price controls and rein in skyrocketing inflation”, says Torné. “In addition, the government should end its heterodox and interventionist economic policies, which have been proven ineffective.” Long-term, the president’s task is to reduce the country’s oil dependency, and in doing so, release Venezuela’s ties to any further price swings. Short-term, there’s clearly no more immediate concern than the issue of currency reform.

Triple threat

Shortly after Chavez’s death, the Latin American nation abolished a failed bolivar-dollar peg in favour of a supply-and-demand-based exchange system. Rather than a single exchange rate, the bolivar’s value is determined by any one of three methods of exchange, therein – at least in theory – eliminating the distortions introduced by black market trading. Successful in crippling the black market rate for all of a week, the unofficial rate overtook the higher Sicad II rate a few days later and rendered the new, unnecessarily complex system redundant.

The disconnect that exists between the official and black market exchange rate has brought with it wayward inflation, and for as long as the government fails to close the gap, Venezuela’s annual inflation rate could number in the four-digit territory. Maduro’s efforts to reform the exchange regime, stem the currency’s decline and protect dwindling reserves will see one key but minor modification made to the existing formula. In it, the Sicad I and II rates will be merged into one and a new third rate will bring private brokers into the mix, in the hope of narrowing the gulf between the official and black market rate.

Although Maduro stopped short of any specifics, the reform marks a vital first step in combatting the current situation, whereby high inflation rates are making even basic goods increasingly hard to come by for the average Venezuelan. Still, critics insist that the latest attempt to remedy the situation amounts to only minor tinkering of a system that requires nothing short of an outright overhaul. Then and only then can the country begin to close its runaway fiscal deficits, which, as of January, came to an estimated 20 percent of national GDP. “Details were sparse, but we can be confident that it will amount to another huge devaluation of the currency, likely exacerbating inflation”, says Gregan Anderson, Latin American Analyst at Business Monitor International.

“The government’s greatest challenge stems from the fact that the changes necessary to revive the economy – devaluing the currency, extending an olive branch to the oft-maligned private sector, and especially pulling back government spending – also threaten to alienate their dwindling base of political support. We expect social unrest will re-emerge and significantly intensify in the coming months, and the government will struggle to reverse the rising tide of discontent, and may resort to increasingly heavy-handed suppression of dissent.” Latin America’s worst performing nation requires far more than a few minor tweaks if it is to escape a looming crisis, and for Maduro to make good on his six-month turnaround, he must first introduce radical reform and concede that the concessions made so far have come up short. What’s important now is that the government takes heed of new record low oil prices and uses the opportunity to introduce much-needed structural reforms before the situation worsens.