Crime doesn’t pay, as the saying goes. But in the case of the US criminal justice system, it often does for the private companies housing the country’s many offenders. Over the last few decades, as repeated US presidents have sought to appear tough on crime, the US’ prison population has soared (see Fig 1). At the same time, private institutions have leapt to the aid of budget-conscious governments and offered to house many of the country’s prisoners.

However, while the number of Americans being locked up has soared, so have the private institutions’ profits. And while many people will be thankful that criminals are being kept off of US streets, there are also considerable concerns over both the treatment of those incarcerated, as well as the motives of the institutions profiting from their sentences.

Tougher stance

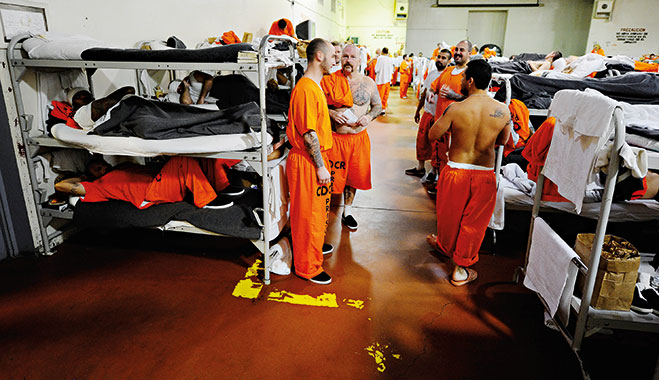

The statistics surrounding the US prison system are stark: while the country is home to only five percent of the world’s seven billion-strong population, it caters for around 25 percent of its prison population. Around 2.2 million people are imprisoned in the US, which equates to around one in every 100 Americans. This figure has steadily risen over the last few decades, and many believe that it is the advent of the ‘War on Drugs’ that has led to such an explosion in the prison population.

While the US’ prison population has soared since the 1980s, other democratic countries have maintained a far lower ratio of incarcerated citizens

In a recent article, Laura Tyson – a former chair of the US President’s Council of Economic Advisers under the Clinton administration – and former McKinsey & Co Director Lenny Mendonca wrote that the reason for this surge in America’s prison population was in part down to more severe penalties for drug-related crimes: “The boom in America’s prison population in recent decades is the result of ramped up punitive crime-prevention measures, including tougher drug penalties and mandatory minimum sentences, backed up by growing numbers of police and other law-enforcement officials.”

While the US’ prison population has soared since the 1980s, other democratic countries have maintained a far lower ratio of incarcerated citizens. Indeed, the US has a prison population of between five and 10 times more per capita than that of any country in Western Europe, according to Tyson and Mendonca.

They added that the cost of keeping all these prisoners incarcerated, alongside paying for bigger police forces, is putting a strain on both state and federal budgets: “Beyond the financial costs of larger police forces and increased pressure on the judicial system is $60bn a year in spending on state and federal prisons, up from $12bn 20 years ago.”

Perhaps the biggest thing to have transformed the criminal justice system in the last 40 years is the War on Drugs that was begun by President Richard Nixon in 1971, but was enthusiastically scaled up during the 1980s by President Ronald Reagan. As a result of tough new laws around drug use, the number of people being locked up skyrocketed in just a few short years.

Stuck in a perpetual rut

One of the many consequences of this new tough approach to drug use and selling was that the law would disproportionately punish people in poorer communities: it would target people ravaged by drug dependency, with little sympathy for their conditions. At the same time, these poorer communities also tended to be trapped within a cycle of crime, as once someone has been arrested on drug offences, they find it increasingly difficult to get gainful employment.

In the 2012 documentary This House I Live In – which looks at the US’ drug sentencing laws and prison system – director Eugene Jarecki shows how prisons have effectively created a permanent underclass and trapped large swathes of society in a life of crime and reoffending.

According to David Simon, a former crime journalist and creator of acclaimed television drama The Wire, mandatory minimum sentences – mostly for drug offences – were not working, and in fact they were leading to increased crime. He told Jarecki in the documentary: “It’s one thing if it was draconian and it worked. But it’s draconian and it doesn’t work. It just leads to more.” By institutionalising people in prisons for small drug offences, it is exposing them to people who are far more accustomed to crime than they would otherwise experience.

Another consequence of the War on Drugs is the rocketing cost to the taxpayer. In a 2008 report conducted by Harvard economist Jeffrey A Miron, it was suggested that the US Government could save around $41.3bn in enforcement and incarceration costs if it was to legalise drugs, and therefore reduce the prison population (see Fig 2). In recent years, many states have sought to relax their laws on drug policy, helping to alleviate the prison population. However, mandatory minimum sentences remain, swelling that population.

Over the last few decades, the US private prison industry has ballooned in size, and is now thought to be a multibillion-dollar market. According to the US Department of Justice, in 2013 there were around 133,000 state and federal prisoners being housed in privately run prisons. This accounts for over eight percent of the country’s total prison population. This trend has steadily grown in recent decades.

Another study conducted in 2012 looked at the prison system in Louisiana, and in particular the large numbers of inmates that private institutions were housing. According to the study by New Orleans’ The Times-Picayune, more than half of the state’s 40,000 inmates were in private prisons. Elsewhere, it was reported in The New York Times in 2012 that over half of the country’s immigrant prisoners were held in private institutions.

While the costs of keeping so many people in prison are huge, in some instances it makes financial sense for the companies running the prisons: they are offered tax incentives to have high numbers of prisoners, as it means that there are fewer criminals on the streets. However, in reality it usually means that people are being locked up for relatively minor misdemeanours so that states fall down on minimum occupancy clauses.

According to a 2013 study by organisation research and policy centre In The Public Interest (ITPI), private prison companies are gaining considerable profits off the back of so-called ‘lockup quotas’ and tax benefits for crime prevention. The study, titled Criminal: How Lockup Quotas and Low-Crime Taxes Guarantee Profits for Private Prison Corporations, outlines how these private prison companies are gaining lucrative contracts that require high occupancy rates.

While having plenty of people in prison might suggest that such companies are keeping the public safe, in actuality it is in the interest of the authorities to go after people with strict penalties, even if they’ve committed seemingly less serious crimes.

Private provision

The US’ prison system is increasingly run by private institutions (see Fig 3), and the importance of their role is growing. A number of large companies operate prisons throughout the country on a profit basis, including the two leading firms, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and the GEO Group. CCA currently has more than 65 correctional facilities across the US, with a capacity of around 90,000 beds. The GEO Group has operations all over the world, with facilities in North America, Australia, South Africa and the UK. As a result of their influence, these companies have played a key role in the formulation of the US’ criminal justice laws.

Indeed, these firms have been strong proponents of laws that include mandatory minimum sentences, which have helped to deliver record numbers of incarcerations. According to the ITPI report, both the CCA and GEO Group have “supported laws like California’s three-strikes law, and policies aimed at continuing the War on Drugs”.

It added: “More recently, in an effort to increase the number of detainees in privately run federal immigration detention centres, they contributed to legislation, like Arizona Senate Bill 1070, requiring law enforcement to arrest anyone who cannot prove they entered the country legally when asked.” The ITPI also brought up a statement made in the CCA’s 2010 annual report, which highlighted how it worried about any softening in criminal justice laws: “The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction or parole standards and sentencing practices, or through the decriminalisation of certain activities that are currently proscribed by our criminal laws.”

the CCA has been criticised in particular for its persistent lobbying efforts in recent years. It has spent considerable sums of money to influence various government departments to support it in recent years. According to a Huffington Post investigation in 2012, a reported $17.4m was spent by the CCA on lobbying the Department of Homeland Security, US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, Congress, and the Bureau of Prisons between 2002 and 2012.

The ITPI report highlights the case. In 2012, the CCA approached 48 state governors about the prospect of buying their publicly run prisons. In return for purchasing the prisons and running them over a 20-year contract, the CCA would require a 90 percent occupancy guarantee from the states. Were prisoner levels to fall below 90 percent, then the state would have to pay the company for the shortfall. This would incentivise states to lock up as many people as possible, and for as long as possible. While no state agreed to the CCA’s offer, there are a number of private prisons that have already secured such contracts from local governments for their prisons.

According to the ITPI report: “Bed guarantee provisions are also costly for state and local governments. As examples in the report show, these clauses can force corrections departments to pay thousands, sometimes millions, for unused beds — a ‘low-crime tax’ that penalises taxpayers when they achieve what should be a desired goal of lower incarceration rates.”

As much as 65 percent of prison contracts that the ITPI studied included occupancy guarantees and quotas, as well as penalties if those beds weren’t filled. Many of these quotas tend to range from between 80 and 100 percent, with the states of Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Virginia all being tied to contracts that require between 95 and 100 percent occupancy. In Arizona, three privately run prisons have 100 percent occupancy quotas, despite the cost to the state for housing each prisoner rising by almost 14 percent for each year of the contracts.

Elsewhere, Ohio’s Lake Erie Correctional Institution has a 20-year contract that requires a 90 percent quota, but the facility has reportedly faced issues with overcrowding, as well as safety concerns. “These contract clauses incentivise keeping prison beds filled, which runs counter to many states’ public policy goals of reducing the prison population and increasing efforts for inmate rehabilitation,” the report noted.

The ITPI added: “The private prison industry often claims that prison privatisation saves states money. Numerous studies and audits have shown these claims of cost savings to be illusory, and bed occupancy requirements are one way that private prison companies lock in inflated costs after the contract is signed.”

Reforming the flawed system

Pressure to reform America’s prison system has come from unlikely sources. While the ongoing Republican presidential contest has garnered the usual tough talk over the War on Drugs and sentencing, a visit by Pope Francis to the US in September saw him call for a focus on the rehabilitation of criminals, rather than mere punishment. “It is painful when we see prison systems which are not concerned to care for wounds, to soothe pain, to offer new possibilities,” he said. “It is painful when we see people who think that only others need to be cleansed, purified, and do not recognise that their weariness, pain and wounds are also the weariness, pain and wounds of society.”

Reacting to his comments, Holly Harris, Executive Director at the prison reform group Justice Action Network, said that Pope Francis was “removing the stigma” around how criminals are treated: “We’re no longer talking about an obscure minority of people – this is something that impacts everyone in America. When you’re sitting in church this morning and look to your left and your right, odds are one of those people has a criminal record.”

The pope’s comments came two months after President Barack Obama, going into the final 18 months of his presidency, revealed his ambitions for reforming the criminal justice system. In July, Obama announced his plan to overhaul a number of contentious areas within the law, with a focus on scrapping mandatory prison sentences, addressing racial disparities in sentencing, cutting the use of solitary confinement, and slowing down the soaring cost of incarceration. In a speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), Obama described the current system as one where society was turning “a blind eye to hopelessness and despair”.

Instead, President Obama said he wanted to offer the chance to those in the prison system to be rehabilitated into society: “While people in our prisons have made some mistakes, and sometimes big mistakes, they are also Americans and we have to make sure that, as they do their time, that we are increasing the possibility that they can turn their lives around. Justice and redemption go hand in hand.”

It seems that politicians from both sides of the political spectrum are eager for there to be some sort of reform. In bipartisan legislation proposed by Republican Senator Mike Lee and Democratic Senator Richard Durbin, sentencing in the US could become much more efficient. The Smart Sentencing Act of 2015 would look particularly at mandatory minimum sentences, although it would refrain from removing them entirely.

Senator Lee said: “Our current scheme of mandatory minimum sentences is irrational and wasteful. By targeting particularly egregious mandatory minimums and returning discretion to federal judges in an incremental manner, the Smarter Sentencing Act takes an important step forward in reducing the financial and human cost of outdated and imprudent sentencing policies.”

It is similar to the Smart Sentencing Act of 2013, which failed to pass through Congress the same year. This time, the act is a bi-partisan effort that will look at reducing mandatory minimum sentences from 10 years or more to five years or more, as well as reducing some sentences from 20 years minimum to 10 years minimum. Michael Collins, policy director at advocacy group Drug Policy Alliance, told The Guardian in July that mandatory minimum sentences must form a central part of any sentencing reform. “You cannot talk about sentencing reform without addressing mandatory minimums. It’s the main driver of mass incarceration in this country.”

As Obama embarks on creating a legacy for his two-term presidency, the prospect of a meaningful reform of the prison industry has become more real. Everything seems on the table in terms of reform, with serious consideration being given to reducing mandatory minimum sentences and putting the onus on institutions to encourage rehabilitation of inmates. While it may not mean longer-term profits for private institutions, it may just help improve society.