Top 5

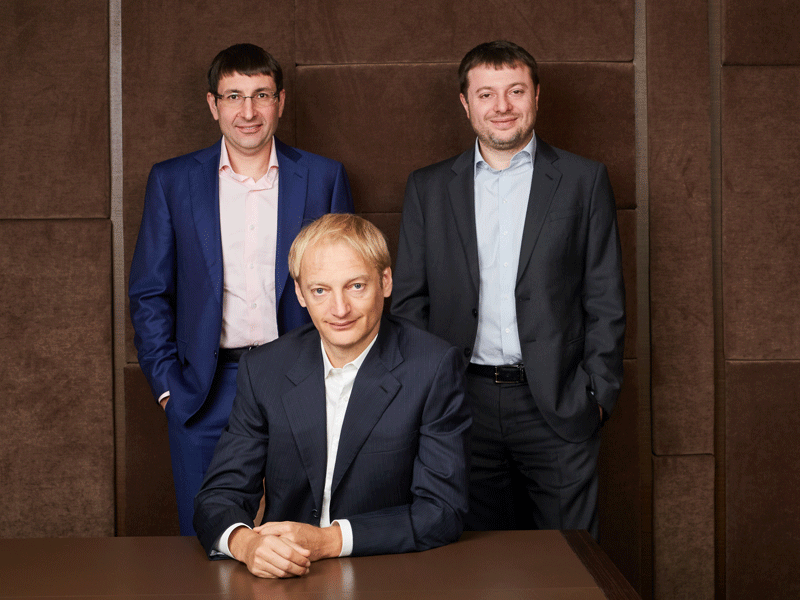

Though today it is one of the biggest banks in Russia, Sovcombank started out from humble beginnings. Under the name Buoykombank, the bank was incorporated in November 1990 in the small town of Buoy, which can be found in the northern region of Kostroma. For over a decade, it performed well as a local bank, servicing the financial needs of the people of Buoy. But this institution was soon to extend much further than the borders of Kostroma: a new chapter in the bank’s history began when two brothers, Sergey and Dmitry Khotimskiy, together with their business partner Mikhail Klyukin, bought Buoykombank outright.

During Sovcombank’s early years, it operated under a traditional banking model, with a particular focus on retail banking for pensioners

“We bought Buoykombank in 2001 and every one of us thought that it was a temporary project,” said Sergey Khotimskiy, co-founder and First Deputy CEO of the bank. “We wanted to buy a small regional bank for $300,000, get a foreign exchange licence, transfer it to Moscow, and then sell the bank for $1m – that was the business plan. But for some reason, we still haven’t sold it. We really like banking and don’t want to do anything else.” Instead, with 100 percent of the bank’s shares in tow, the trio embarked on a complete transformation. This began with a new name – Sovcombank – in 2003.

During Sovcombank’s early years, it operated under a traditional banking model, with a particular focus on retail banking for pensioners – a niche area in Russia’s financial services sector that most banks shied away from at the time. Banks shared a reluctance to lend to pensioners because of their generally low incomes, as well as their shorter life expectancy compared with those of their counterparts in developed economies. In Russia, the average life expectancy is 71.9 years – below the global average of 72 and a far cry from those of developed economies, with the US, Germany and the UK boasting expectancies of 78.5, 81 and 81.4 years respectively, according to the World Health Organisation. This fact, together with the specific staff training and expertise needed to serve pension clients, held most traditional banks back.

Sovcombank, however, embraced the challenge. Thanks in large part to its prudent financial behaviour, the bank was able to turn this niche sub-sector into an opportunity for growth – one that few others in the market had recognised. Though the loans were small and often made on a short-term basis, the cost of risk was among the lowest the market had to offer (see Fig 1). This was key, particularly as interest rates were at the same level as in other, riskier areas.

With Sovcombank’s cost of risk being among the lowest in the country, its expansion soon took place: starting life as a single office in Buoy, today the bank’s retail segment has over 2,000 offices in more than 1,000 towns across Russia, serving some 3.2 million customers.

With Sovcombank’s cost of risk being among the lowest in the country, its expansion soon took place: starting life as a single office in Buoy, today the bank’s retail segment has over 2,000 offices in more than 1,000 towns across Russia, serving some 3.2 million customers.

This widespread presence was helped by a series of strategic acquisitions over the past 10 years, which have seen the bank become one of the most successful in the market. Between 2014 and 2017, Sovcombank achieved an average reported ROE of 50 percent (see Fig 2), making it the most profitable banking group in Central and Eastern Europe in both 2016 and 2017.

Foundations for success

Dmitry Gusev, CEO of Sovcombank, puts the bank’s success down to a number of factors, starting with the context in which it was established. He told World Finance: “We were quite lucky starting our banking business in the period when the national banking system was only just being formed, so there were lots of opportunities out there.”

He continued: “If we look into the current champions – those privately owned banks that have managed to get into the group of Russia’s competitive banks – we see that many of them started at exactly the same time. Because the growth of the national banking system was so huge, we saw that not only our bank, but also many others, grew significantly.”

However, as Gusev explained, many banks were not completely capitalised during that period, meaning they did not have a capital base in place to fully support growth. Sovcombank, on the other hand, maintained a prudent approach and expanded with the pace of its new profit generating capacity. It is through this strategy that Sovcombank has since established itself as one of the biggest privately owned banks in Russia.

However, as Gusev explained, many banks were not completely capitalised during that period, meaning they did not have a capital base in place to fully support growth. Sovcombank, on the other hand, maintained a prudent approach and expanded with the pace of its new profit generating capacity. It is through this strategy that Sovcombank has since established itself as one of the biggest privately owned banks in Russia.

While the bank has evolved in numerous ways since 2003, one core aspect of its operations continues: pensioners and pre-pensioners remain one of Sovcombank’s main clientele. That said, the bank is also in the process of diversifying its clients significantly with a new line of products, which includes installment cards, home equity loans, mortgages and automobile loans that are aimed at younger customers.

Meanwhile, Sovcombank’s corporate and investment banking (CIB) arm continues to grow. Today, it provides financial services to the biggest private and state-owned corporations in Russia, as well as to regional governments and municipalities. In 2017, Sovcombank was ranked as the number one privately owned arranger of domestic bonds in Russia by Bloomberg. Further, Sovcombank’s CIB arm enables some 350,000 micro, small and medium-sized businesses to engage in public procurement, issuing around 26 percent of all bank guarantees needed for state and municipal procurements in the country

A winning formula

Over the past five years, Sovcombank has led 10 successful M&A deals, which in turn has enabled it to increase its capital base considerably. What makes this achievement all the more noteworthy is that most M&A transactions in Russia during this time have been unsuccessful. Indeed, this is a trend that can be seen all around the world – simply, M&A successes have not been favourable to acquirers for some time now.

“Despite global trends, we have been successful in each and every one of our M&A transactions,” said Gusev. He puts this success rate down to three key pillars: “First of all, who you are buying from is very important. Every seller that we deal with is a very reputable organisation – either foreign, such as a big foreign bank, or a very successful privately owned Russian group. Dealing with the purest, cleanest banks gives us valuable expertise in the most attractive niches.

“Second, we have never tried to just buy whatever is being sold – we always wait for really good transactions that, while increasing our competitive advantage, also boast good financial terms and offer a favourable price for the institution in question. And the third pillar is that we are always very quick to complete the integration process.”

The bank’s record reflects this: its longest M&A integration process took nine months, while the fastest was concluded in just four. Gusev said: “This short period of time ensures that the transaction does not lead to what I call the ‘disorganisation of the acquirer and the target’. I believe that if you spend too much time walking in parallel structures, then most of the competitive advantages that you plan to utilise after the acquisition end up being wiped out.” This strategy has worked superbly well for Sovcombank, not only at a time in which M&A activity has been low, but also during a period of relative economic hardship for Russia.

Overcoming impediments

The 2008 financial crisis rocked the world and had a huge impact on the Russian economy. The effect of this external shock was exacerbated further by the bursting of Russia’s asset bubble and a collapse in oil prices, which led to considerable capital withdrawals from the country.

It is remarkable that while countless entities in Russia have struggled during tumultuous times, Sovcombank thrived

Describing the atmosphere at the time, Sergey Khotimskiy said: “Initially – in the segment of private banks, and to a lesser extent the state-owned banks – bankers didn’t really value a bank’s capital. When a bank invests in assets that can’t be sold today, it automatically means that for some reason the bank either does not protect its capital or does not plan to give the money back quickly. And it was with this ‘birth trauma’ that many Russian private banks began their journey.

“When the banking system started to develop, the bankers thought: ‘OK, we collected the customers’ money, so now we invest it in real estate projects.’ With this approach during the time of hyperinflation in the 1990s, banks normally had time to wrap a project in money, but when they tried to repeat this process in the 2000s, the crisis of 2008 hit them and those models very hard. A huge number of banks received ‘holes’ in their balance sheets due to the reduction of liquidity and the value of such assets. As a result, lots of them did not survive.”

This scenario marked the first significant purge of Russia’s banking system. But while the external shock of the 2008 crisis had an irrefutable effect, the country was better positioned fiscally than it had been in the past, taking lessons learnt from the 1998 Asian financial crisis, which had dire consequences – including a default on domestic debt.

But just as economic recovery began to sink in, Russia was hit with another crisis in 2014. It started with an enormous – almost 50 percent – plunge in the price of oil. Being heavily dependent on the oil sector, the government was forced to make swift and significant budget cuts. It did so primarily through public sector salaries, all the while providing support to the companies affected by taking assets from the National Welfare Fund.

2000+

Number of Sovcombank retail segment offices

1000+

Number of Russian towns in which Sovcombank has a retail segment office

3.2m

Approximate number of Sovcombank retail customers across Russia

50%

Average ROE Sovcombank achieved between 2014 and 2017

No.1

ranked privately owned arranger of domestic bonds in Russia in 2017

350,000

Micro, small and medium-sized businesses assisted by Sovcombank’s CIB in public procurement

Then came another blow: economic sanctions were imposed by the US and Europe in a bid to curb Russia’s energy future. By curtailing access to western technology at a time when Russia was planning to tap new deep-sea, shale and Arctic reserves, the US and Europe took aim at the very foundation of Russia’s economy. Unsurprisingly, sanctions were followed by a collapse of the ruble, which had a sudden and devastating effect on the economy.

The culmination of the crisis came on December 17, 2014 – a date that is now known as Black Wednesday in the history of Russia’s financial system. Khotimskiy described the situation: “The Central Bank of Russia [CBR] sharply increased its key interest rate by 6.5 percentage points to 17 percent. The exchange rate went off the scale and the market began to panic. Regulators introduced unprecedented measures to support the banks, which were engaged in patching holes for a week; trying desperately to stop the outflow of deposits and maintain their balance sheet. At the same time, Moody’s was the first of the three international ratings agencies to announce an increase in the likelihood of the Russian Government imposing a moratorium on the repayment of foreign debts. Furthermore, Moody’s did not rule out a default of the government on its own obligations. Meanwhile, S&P began revising the sovereign rating of Russia with a negative outlook, in the direction of the ‘garbage’ zone.”

Khotimskiy continued: “The foreign investors came back from the Christmas vacation and immediately began a massive sell-off of Russian securities. On both sides of the ocean, investors threw off the paper at any price. The discount was 10 percent.”

Amid the crisis, Sovcombank had to work quickly and decisively. “The supervisory board of Sovcombank met on December 29 and reviewed the 30 largest issuers in order to set limits on them. From January 2, 2015, the entire team in Sovcombank’s treasury unit worked from morning until late in the night, buying paper at the bottom. Between January 2 and 10, Sovcombank bought bonds for $500m; by the end of January, due to the growth of securities in the price of this strategy, the bank achieved a profit of $50m. We were not the only ones who worked on those days, but there were almost no banks that managed to raise their limits and ensure the work of the treasury unit 24/7,” said Khotimskiy.

Chances from challenges

Far from showing signs of retracting, the US introduced new sanctions against Russia in both 2017 and 2018. “In general, sanctions are not very good for the Russian economy, and the economy is struggling to adjust. But at the same time, I think they provide an opportunity for healthy organisations,” Khotimskiy explained. “Due to the sanctions, many foreign entities have left Russia, which has created a window of opportunity for privately owned banks to compete for the best clients, both retail and corporate.”

It is remarkable that while countless entities in Russia have struggled during these tumultuous times, Sovcombank did more than just survive: it thrived. This success is rooted in the bank’s far-sighted approach to banking. “We always try to manage the business in a countercyclical way, which means that during good times, we keep our capital base and liquidity in a safer mode than most of our privately owned competitors,” Khotimskiy told World Finance. “This means that when bad times come, we always have a cushion in place.”

In fact, the bank was able to utilise a variety of opportunities that it recognised during both the 2008 crash and the Russian economic crisis of 2014. “During these periods of time, we managed to buy very attractive assets and secure very attractive clients. So we actually made more money and were more successful after those crises than ever before,” Khotimskiy noted.

“This strategy works very well in Russia and we think it will continue working in the future because the economy is very volatile, and whenever people are scared about what’s going on in Russia’s economy, there are amazing opportunities to be found,” he continued. “Russia has proved again and again that it can survive external shocks, and in every shock there is an opportunity.”

A foreign exodus

Given the precarious economic landscape after 2008, a number of foreign banks have gradually reduced their investments in Russia. According to outlets in the Russian media, the total loss amounts to around $2bn.

Khotimskiy explained the reasons behind this shift: “I think it’s very challenging for a foreign institution to be successful in Russia right now. I think those institutions that are still here are very successful and Russia plays quite a significant role in their global balance sheets. They are Italian, Austrian and French banks; even Citibank is very successful in Russia. But I think for newcomers right now, the political situation is not very favourable. I also think the fact that we saw a significant exodus of different foreign banks proves that even though some champions remain, in general, the environment is very tricky.”

While this environment has closed off various opportunities for foreign banks, it has opened many new doors for domestic institutions. That said, Russia’s prospects for foreign portfolio investment remain very attractive. Khotimskiy told World Finance: “I think Russia is a darling for portfolio investors because of its volatility. For those professionals that understand Russia well enough, I think Russia always proves to be a land of opportunities. Because when everyone becomes scared and a huge sell-off is on the way, you can always make great use of that.”

Clean-up time

Against this complex backdrop, another momentous shift has been underway. Indeed, the past five years have been nothing short of decisive for Russia’s financial sector. Under the leadership of Elvira Nabiullina, who was appointed as the new head of the CBR midway through 2013, a large-scale and unprecedented clean-up of the industry has taken place.

For those professionals that understand Russia, I think it always proves to be a land of opportunities

When Nabiullina took to the helm of the CBR, she was faced with an ailing and bloated banking sector. In the 2000s, a booming oil sector helped mask the problems facing Russia’s banks, but the 2008 crisis swiftly brought them to the surface. Of greatest concern were deficient regulations, the prevalence of bad loans and a lack of capital. Fortunately, under Nabiullina, the CBR has deepened oversight in the sector by enforcing more robust liquidity and capital adequacy requirements.

In the early stages of the initiative, the CBR focused on curtailing suspicious capital outflows, under the belief that billions upon billions have left the country, and purging so-called ‘pocket banks’. The post-soviet term refers to institutions created by industrial groups to service their businesses’ financial needs; in some cases they also acted as fronts for money laundering. The CBR took on banks that were previously considered untouchable, gradually tightening rules along the way, including those related to lending to the banks’ owners.

Five years later, Russia’s clean-up of its banks is more than half complete: from more than 900 banks in 2013, around 500 are left today. While some have collapsed, others were bailed out by the state. The biggest among these were B&N Bank, Otkritie, and Promsvyazbank, which were all seized by the CBR in 2017.

Meanwhile, since mid-2017, only financial institutions with strong ratings from Russian ratings agencies ACRA and Expert RA have been entitled to state funds and instruments. Another new rule – though only for the interim – involves meeting capital requirements and having balance sheets of a certain size in order to access state funds.

The CBR’s robust work is lauded for having prevented another financial crisis, while helping to strengthen healthy banks in its wake. “Sovcombank is one of the beneficiaries of this process, because we were always suffering from the competition of organisations that never really bothered to stick to the rules, as well as those that were under-capitalised and managed to grow without a real capital base,” said Khotimskiy.

“From this point of view, the clean-up is very important: it’s clear that there are no significantly big privately owned banks that can work the way they used to before. So we think that the job done by the central bank is really a base for both significant economic growth and the healthy growth of the banking system in the future.”

Consequently, in recent years, the Russian banking sector has been showing impressive figures in terms of returns on capital and assets. “Obviously, because inflation rates are low, the returns that we used to see are no longer on the table,” Sergey Khotimskiy explained. “However, at the same time, Russia still has one of the highest equity returns on assets in the world, so I think that we’ll be seeing double-digit returns in most banks. As far as Sovcombank is concerned, for the last 10 years, our average ROE was more than 30 percent, and we expect it to stay above 20 percent for the next three to five years.”

The march of technology

The future for Russia’s banking sector looks promising – an outlook that is strengthened further by its impressive adoption of cutting-edge financial technology. Unlike other markets, however, this drive is not led by fintech players: according to Gusev, it actually comes from the banks themselves.

The past five years have been nothing short of decisive for Russia’s financial sector

“The Russian banking system is a unique financial system in this sense. The general state of Russian banking is very developed in terms of technology, and I think some champions – both state and privately owned – really are the key drivers of the digitalisation of financial

systems,” Gusev noted.

Over the past year or so, many successful fintech start-ups in Russia have been acquired and integrated into domestic financial institutions. Gusev said: “We think that’s because very strong banks are paying huge attention to digitalisation; I think this trend is probably going to stay the same for some time. While many fintech companies will be at various stages, the most advanced ones will continue to be bought out by the banks themselves.”

Speaking about some of the most exciting technology the market has to offer, Gusev was clear about what stands out for him at present: remote biometric identification (RBI) and Russia’s Unified Biometric System (UBS).

“We live in the digital age, and we can hardly imagine our everyday lives without mobile devices,” Gusev said. “We are regular users of mobile communication, and at the same time we still can’t fully function without offline visits to a bank office; without physical identification on the spot. In my opinion, this is a relic that should be addressed as soon as possible.”

This is where RBI and UBS come in, as they allow banks to identify clients remotely, thereby eliminating the need for their physical presence in brick-and-mortar bank branches. “I think this is a game-changer for the industry, and in several years, we will see more and more bank branches shut down,” Gusev told World Finance. “Only those banks that manage to turn their outlets into centres for consulting and for sales without any operational work will be really successful in reaching out to their clients in remote locations, and even in big cities.”

Sovcombank was one of the first credit institutions in Russia that began to gather the biometric data of its customers and transfer them to the UBS. “Of course, we can’t say that the system is working flawlessly at present, or that there are no problems with data transmission, but this can be expected because the process is still in its very early stages,” said Gusev.

He continued: “As for the advantages, it should be understood that this issue can’t be considered only in the banking context – in the future, we are thinking about creating a universal digital profile of the client, which they can use to obtain services in the bank and to solve a much wider range of problems and tasks. This point, in my opinion, should be explained to our customers, as the question of the speed of filling the UBS is not only a question of the activity of banking organisations, but also a question of the financial literacy of users.”

Aside from RBI, Gusev notes that the other technologies set to transform the industry include the introduction of a system of fast payments, application programming interfaces and technology based on a distributed registry system. Gusev said: “The fifth is, of course, end-to-end protocol, which allows you to combine different databases, and on this basis, to create a universal digital client profile. All of these technologies are interconnected in one way or another, and complement each other. They have all arisen due to the fact that the very philosophy of human life has changed. Indeed, we are increasingly entering the age of the digital economy, and this is changing our perception of the most mundane things, including banking and financial services.”

As the industry hangs on the cusp of this new future, some retrospection is important. Undoubtedly, a great deal has happened in Russia’s financial sector over the past decade – the last five years, especially so. This transformation can be attributed to a variety of factors, from a series of drastic external shocks to a dramatic clean-up of the industry. As the CBR’s initiative continues, more robust regulations will be implemented, while the unhealthiest banks will be removed from the landscape. Interestingly, this is not the only ongoing factor at play: the industry is being shaped further by new technology and the new opportunities that it presents.

Sovcombank is well positioned to capture both. As demonstrated by its track record, the bank rarely fails to notice the opportunities that can be found, even in the most difficult of circumstances. All the while, it stays ahead of the curve, never resting on its laurels, working countercyclically and adopting the latest innovations in the industry to stay profitable, while remaining a key partner to its clients, both big and small. Russia’s financial industry has faced an incredible onslaught of challenges in recent years, but out of the clouds of doubt, the likes of Sovcombank continue to shine through.