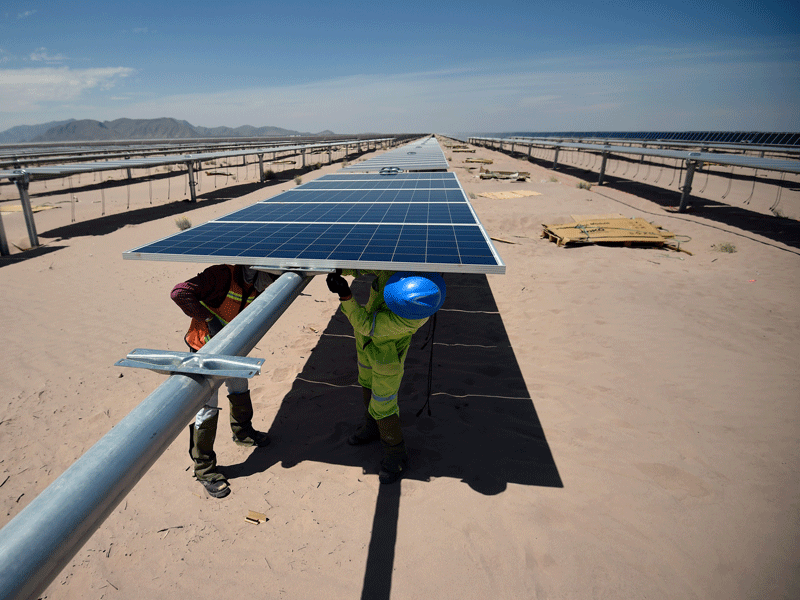

Latin America has a considerable potential for renewable energy; large rivers, sunny deserts and favourable wind conditions provide abundant opportunities for hydroelectric, solar and wind power. As the region is increasingly taking advantage of these resources, the value of renewable energy deals in Latin America has surged from $975m in 2013 to $2.5bn in 2016. Investment is expected to expand further as more countries set renewable energy goals and offer financial incentives. With so much activity afoot, Canales Auty advises clients across Latin America on the importance of understanding the environmental, social and commercial risks of any project they invest in.

Canales Auty advises clients on the importance of understanding the environmental, social and commercial risks of any project they invest in

At present, Latin American governments are in the process of setting new renewable energy goals in order to meet multiple objectives, such as energy security, environmental sustainability and socioeconomic progress. Without a doubt, the Paris climate accord has been a major driver. Under the agreement, numerous countries have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in a bid to limit temperature rises. The accord takes a ‘bottom-up’ approach, with each government determining its own emissions reduction plan. All Latin American governments are signatories of the agreement, and most have incorporated renewable energy goals into their current plans. The policies of Bolivia, Colombia and Mexico in particular provide ample evidence of the region’s current renewable energy push.

The policy drive

The Constitution of Bolivia obliges the state to develop and promote different types of energy, including, of course, alternative energies. The establishment of the Ministry of Energy in 2017 gave further importance to the sector; today, Bolivia has a strategic plan in place to become the region’s energy hub, exporting both renewable and non-renewable energy to neighbouring countries. The policies actively being implemented include the diversification of the energy matrix and the development of renewable energy with a low socio-environmental impact. As such, state-owned companies have been conducting tenders for turnkey projects, with a particular focus on hydroelectric ventures.

In Colombia, significant hydro, wind and solar resources exist. In 2013, the country made broad renewable commitments, including a target for 6.5 percent generation capacity from renewables by 2020 (with the exemption of large hydro). Recent policy changes have supported these goals further. Funds finance up to 80 percent of plans, programmes and investment projects for conventional and renewable projects in non-grid-connected zones. Moreover, legal changes in 2014 have encouraged capital investment in renewable energy projects through income tax deductions, VAT and import duty exemptions, and accelerated depreciation for investments.

In 2008, Mexico enacted the Law for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Transition Financing, establishing its own ambitious renewable energy targets in the process. Constitutional reforms in 2013 liberalised the energy sector, permitting private investment and transforming the power sector into a competitive wholesale market. Mexico’s renewable policy has become highly advanced in record time; the International Energy Agency considers the reform “one of the most ambitious, comprehensive and well-developed reforms undertaken in the world since the 1990s”.

The 2014 Electricity Industry Law, meanwhile, has sought to integrate renewable energy into the national grid, with the aim of reaching 25 percent integration by 2018, 30 percent by 2021 and 35 percent by 2024. Market liberalisation is also helping these targets to be achieved; Mexico is now conducting its fourth tender and has awarded almost 40 companies with renewable energy contracts, mostly in wind and solar. Furthermore, Mexico’s development bank, Nacional Financiera, offers financing with accelerated depreciation, while the country’s market for clean energy certificates has begun providing further incentives this year, too.

Considering environmental risks

Latin America has a diverse environment with large areas of protected reserves. Each country has strict rules and regulations governing permits, public consultations and environmental assessments. Each of these processes is time consuming, with bureaucratic administrative procedures generating project risk.

In Bolivia, which has one of the most diverse environments in the world, the constitution provides ‘Mother Earth’ rights, recognising the environment as an entity with legal entitlements and allowing individuals or social organisations to take legal action in the name of the environment.

Over the past year, the Chepete-Bala hydroelectric power plant project has fallen victim to this law, with protests and delays arising as a result. Bolivian environmental law relates to the project’s continuation, as well as compliance with environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and environmental quality control, which involves monitoring, inspection and environmental audits. The extent of these assessments depends upon the project type, with EIAs required to take place prior to the commencement of any work activities. Violations of environmental regulations can result in fines, project rescissions and criminal prosecutions.

In Colombia, the need to obtain an environmental permit depends upon business activity and the potential impact on renewable resources. The National Code of Natural Renewable Resources stipulates that anyone seeking to use natural resources must first obtain an environmental permit, of which there are 10 types. What’s more, as of 2015, the electricity sector requires mandatory environmental licences. These cover EIAs, as well as social and economic impacts in the area. In Colombia, environmental authorities can impose injunctions and sanctions on companies that violate environmental laws.

Similarly, the Constitution of Mexico recognises the obligation to guarantee environmental conditions and regards sustainability as a key component of national development. The environmental legal framework exists on three government levels: federal, local and municipal. This makes the environmental permit process complex, especially as there are various permit types, which take an average of six months to obtain. Again, permit requirements depend largely on the project type. Federal environmental violations can lead to administrative penalties (fines, cessation, confiscation or relinquishment) and criminal charges. It’s also worth noting that Mexico’s legal framework allows citizens to participate in environmental claims.

Recognising social pitfalls

Article 18 of the United Nations’ (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides indigenous peoples with “the right to participate in decision-making in matters affecting their rights”. Article 32, meanwhile, requires states to “consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples… in order to obtain free and informed consent”. Moreover, the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (ILO 169) seeks to ensure that indigenous people enjoy human rights without discrimination and can participate in decision-making processes that affect their lives. As approximately 11 percent of Latin America’s population is indigenous, the region has become a leader in protecting indigenous rights, with national laws incorporating these international principles.

For instance, the Constitution of Bolivia requires all new projects to carry out a consultation process with affected parties and local communities prior to receiving authorisation. Land use rights and ownership also present a risk, as the constitution grants indigenous populations the right to the use and benefits of the land, as well as the protection of their sacred places. Claims that the land for the Chepete-Bala hydroelectric project is sacred, together with failings in the consultation process, have caused severe delays, as well as protests that have been registered with the UN.

Colombia also applies a prior consultation process with indigenous groups. The constitution states that the government will encourage indigenous involvement where natural resource exploitation is to occur. Between February and July, Energía del Pacífico completed a prior consultation process with four indigenous groups for the installation of two solar power plants. The process was arduous, consisting of: the opening of a consultation period; impact analysis and identification; the formulation of mitigation measures; the formulation of agreements; notarisation; agreements regarding follow-ups; and, finally, the closing of consultation.

With approximately 6.5 million indigenous people, Mexico was one of the first countries to sign and ratify ILO 169, as well as incorporate it into its constitution. Legislation concerning prior consultation of the indigenous population in Mexico is complex, existing at both federal and state levels. The legal framework concerning land rights of indigenous people is similar, and issues related to land ownership, rights of way and social aspects have generated significant delays for some renewable projects, making others unviable altogether.

Commercial tribulations

While international energy companies are accustomed to commercial risks, regional and local interconnection risks are greater than those in developed markets. That said, investments are needed to expand grid capacity, integrate intermittent and volatile generation of renewable energy sources, and secure a stable supply.

Bolivia currently has plans in place to construct 2,822km of domestic transmission lines and a further 1,221km for export projects. As The New York Times recently reported, an additional 12,000km of regional transmission lines are needed to enable cross-border energy integration – a pressing matter for Latin America. Unfortunately, large distances between supply and demand, as well as complex geographical landscapes, complicate this aim. Authorities in both Colombia and Mexico are all too aware of this, which is why Canales Auty is currently advising the Mexican Ministry of Energy on a new 1,200km transmission line that will integrate isolated systems into the expansion of the national grid.

Also crucial to consider are the Equator Principles (EPs), a risk management framework for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risks in project finance. EPs provide a minimum standard for due diligence to support responsible risk in decision-making. At present, 92 financial institutions in 37 countries have adopted the principles. As such, the regional complexities of ensuring environmental and social compliance have become obligatory for obtaining financing, placing a higher governance standard on EPs.

Finally, there are those risks related to the region’s energy markets. In the 1990s, many Latin American governments reformed their power sectors, meaning prices for electricity generators are typically defined in the wholesale and retail markets. The wholesale market is reserved for power generation plants and distribution companies, and is overseen by regulators. This is an area in which governments frequently enact forms of price control, presenting risks to renewable generation. The retail market, on the other hand, serves unregulated users, with prices being negotiable. Consequently, medium and long-term auctions are now a common practice in order to make projects viable.

Despite these challenges, renewable progress in Latin America has been unprecedented. This has spurred more countries to follow suit, with many now committed to incorporating effective renewable energy policies and setting ambitious targets. As such, plenty of opportunities exist for all types of energy, engineering and construction companies, so long as they holistically consider the environmental, social and commercial risks first.