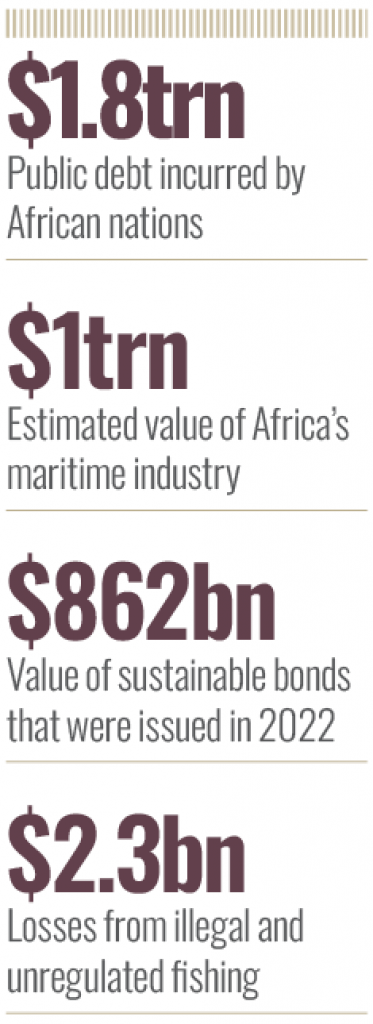

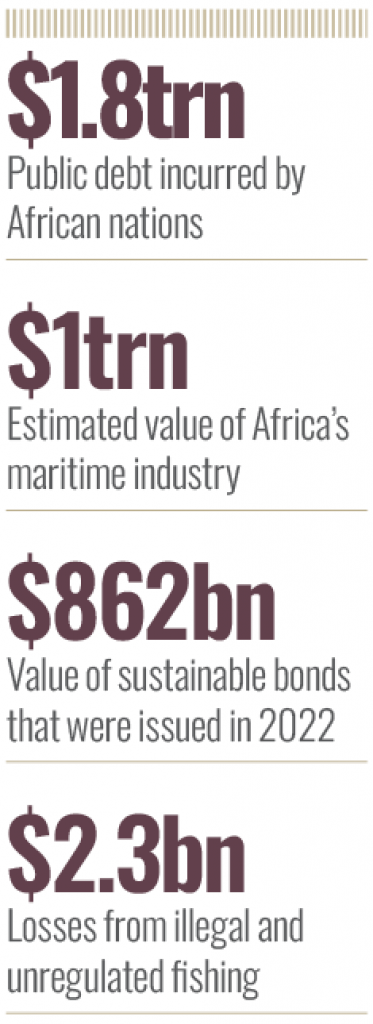

African countries are in dire need of massive resources to finance sustainable development. Having amassed a staggering $1.8trn in public debt over the past two decades to finance infrastructure projects, most nations have limited headroom for conventional borrowing. For this reason, countries are being forced to become creative and innovative in mobilising resources.

In October, for instance, Egypt raised $478m through a Chinese yuan-denominated panda bond, a first by a Middle East and Africa sovereign. Apart from diversifying its financing sources, the primary aim was to escape from high interest rates in the west considering the three-year bond came with an interest rate of 3.5 percent.

Two months earlier in August, Gabon became only the second African nation to issue a blue bond after Seychelles, which in 2018 had debuted the world’s first blue bond, raising $15m. In the case of Gabon, the ‘debt-for-nature swap’ resulted in refinancing $500m of its public debt and unlocking some $163m for marine conservation. The long-term blue bond, which matures in 2038, came with a coupon priced at 6.097 percent. This was lower than the coupons on the repaid bonds, which were between 6.625 percent to seven percent.

“Blue bonds hold a lot of promise,” says Sally Yozell, Director of the Environmental Security Program of the Stimson Center. She adds that Seychelles paved the way for other African nations to undertake blue bonds issuances, including steps for success.

Granted, the debt conversion for ocean conservation in Gabon that came with the tag of a ‘blue bond’ has raised debate over legitimacy. The fact that Gabon’s sole purpose in floating the bond was to refinance its debts has brought about the question on whether ‘blue’ bonds are being abused instead of the proceeds being ring-fenced for protecting and managing the marine ecosystem. The central African nation bought back three bonds, one maturing in 2025 and two in 2031, with a total nominal value of $500m. The buybacks were equivalent to around four percent of the country’s total debt.

Conservation cash

Simone Utermarck, Sustainable Finance Director at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), explains that for blue bonds, the proceeds or an equivalent amount should exclusively be applied to finance or refinance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible green/blue projects. “Gabon is a debt for nature swap, not a use of proceeds bond,” she states.

A month after the Gabon issuance, which was arranged by the Bank of America and fronted by US-based The Nature Conservancy (TNC) that has set up deals worth at least $1bn, ICMA published a ‘practitioner’s guide.’ The objective was to provide issuers with guidance on the key components involved in launching a ‘credible’ blue bond and assist underwriters by offering vital steps that facilitate transactions that preserve the ‘integrity’ of the market.

Away from the legitimacy debate, the consensus is that blue bonds can offer African nations with coastlines a viable source for mobilising resources for conservation. Undoubtedly, Africa’s oceans and waterways are in peril. Wanton pollution, climate change, overfishing, illegal fishing and poor management, among other factors, are threatening to wipe out the socio-economic benefits that come from the water bodies. Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing alone costs Africa over $2.3bn in economic losses annually, according to estimates from the African Union Commission.

The importance of Africa’s blue economy cannot be underestimated. Annually, it generates approximately $300bn, creating 49 million jobs in sectors like tourism, transportation, fisheries and aquaculture. Cumulatively, the annual value of Africa’s maritime industry is estimated to be over $1trn. Marine resources, particularly fisheries, underpin the continent’s sustainable blue economy as well as the food, economic and ecological security of hundreds of millions of people. Fish represent over 20 percent of total protein intake in 20 countries, accounting for approximately 200 million people. In some countries like Sierra Leone and Senegal, it accounts for over 70 percent of protein intake.

Nicholas Hardman-Mountford, Head of Oceans and Natural Resources at the Commonwealth Secretariat, contends that as populations grow and the demand for marine resources increases, Africa must prioritise conservation. “For Africa, it’s about ensuring a sustainable future for its people,” he notes. He adds that the Commonwealth has even developed a Blue Charter to help African countries harness their marine wealth sustainably. Among other things, the charter recognises the potential of innovative financing mechanisms like blue bonds to finance marine conservation.

Global growth

Though still in its nascent stages globally, the blue bonds market is expanding. According to the Stimson Center, 26 blue bonds were issued between 2018 and 2022 amounting to a total value of $5bn. This represented a 92 percent compound annual growth rate. Latin America and South Asia are two regions where the blue bond market is particularly vibrant and innovative. “The increasing presence of major multilateral development banks and financial institutions will likely help the growth of the blue bonds market,” avers Yozell, adding that the launch of the world’s first blue bond index in July this year is bound to accelerate growth.

Notably, the line between blue bonds and green, social and sustainability bonds is becoming extremely thin. In 2022, the global issuance volume across the whole spectrum of sustainable bonds amounted to $862bn, dropping from a record high of $1trn in 2021. The market is forecast to bounce back, with ICMA stating that 98 percent of total sustainable bonds issued globally are aligned with its principles. “In the last five years, a series of blue bond issuances demonstrate a growing appetite for ocean-themed bonds,” notes Utermarck.

For blue bonds, ICMA has designated eight categories that qualify for financing through proceeds of blue bonds. These include coastal climate adaptation and resilience, marine ecosystem management, conservation and restoration, marine pollution and marine renewable energy. Others are sustainable coastal and marine tourism, sustainable marine value chains, sustainable ports and sustainable marine transport. “As the issuance of blue bonds becomes more vibrant in various parts of the world, Africa has a unique opportunity to learn, adapt and implement these financial mechanisms to achieve both economic and environmental sustainability,” observes Hardman-Mountford.

A blueprint for bonds

Seychelles and Gabon have set a precedent. For both countries, issuing blue bonds was a no brainer. In the case of Seychelles, marine resources are critical to its economy. After tourism, fisheries is the second most important sector, contributing 20 percent of the gross domestic product and employing 17 percent of the population. Fish products account for about 95 percent of the total value of domestic exports.

Seychelles paved the way for other African nations to undertake blue bonds issuances

As one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, marine conservation is a matter of survival for the archipelagic nation of 115 granite and coral islands. This explains why Seychelles floated a blue bond with proceeds from the 10-year bond going towards the expansion of marine protected areas, improving governance of priority fisheries and the development of the blue economy. The government also set up funds to provide grants and loans to organisations and companies involved in marine conservation. Gabon, on its part, also needs to prioritise protection of its beaches and coastal waters as a matter of urgency. Apart from losing approximately $610m annually to IUU, the country hosts the world’s largest population of leatherback turtles, as much as 30 percent of the global population of the endangered species. It is also home to one of the largest olive ridley turtle rookeries in the Atlantic, and to the Atlantic humpback dolphin, recently classified as critically endangered.

To protect these species from extinction and preserve sustainability of its coastal waters, the country intends to deploy the $163m raised from the blue bond to finance a new marine spatial plan, improve management in current marine protected areas, strengthen enforcement against IUU fishing and support a sustainable blue economy. Tragically for the country, implementation of these measures now hangs in the balance following a coup that ousted long-serving President Ali Bongo just days after the bond issuance. “The experiences of Seychelles and Gabon provide valuable insights and inspiration for other African countries,” says Hardman-Mountford. The continent has 38 coastal states and a number of island states like Cape Verde, Sao Tomé and Principe, Mauritius, Seychelles and the Comoros. Collectively, Africa’s coastal and island states encompass vast ocean territories of an estimated 13 million square kilometres.

Blue bond buoyancy

Going forward, no doubt more African countries will turn to the global financial markets to float blue bonds to finance marine conservation. However, the level of sophistication, excruciating and complex processes, market conditions and other factors, both internal and external, mean that issuing a blue bond is not plain sailing. Currently, for instance, the high interest rates in western capital markets driven by the US Fed’s policy stances defined by extensive tightening cycles means that sovereigns must be ready to bear the burden of high interest rates.

“The success of blue bonds requires meticulous planning, widespread stakeholder engagement and an unwavering commitment to transparency and long-term marine conservation goals,” notes Hardman-Mountford.

For blue bonds, the bar for scrutiny has been raised following Gabon’s debt-for-nature swap issuance and the fact that TNC has faced criticism for using the ‘blue bond’ tag to help refinance more than $1.2bn of debt globally while generating only $400m for conservation. Going forward, regulators and investors are bound to demand more clarity.