Sign In to continue reading the premium content or subscribe to one of our premium plans:

Already a member? Manage your profile here!!!

Sign In to continue reading the premium content or subscribe to one of our premium plans:

Already a member? Manage your profile here!!!

Sign In to continue reading the premium content or subscribe to one of our premium plans:

Already a member? Manage your profile here!!!

Sign In to continue reading the premium content or subscribe to one of our premium plans:

Already a member? Manage your profile here!!!

In today’s fast-paced world, finding the balance between managing your personal life and excelling in your business can be a challenging endeavour. Time is a precious commodity and your greatest asset, and it often feels like there are not enough hours in the day to cater to both family and business commitments.

From choosing the ideal birthday gift to strategic advice on achieving the perfect work-life balance, a new level of executive service is needed. More aligned to a private concierge, but also spanning lifestyle and personal elements, The Life Curators team are not your average VAs. Spanning the entire globe, our team is international, multilingual, highly educated, and extremely well-connected.

Procuring a range of services gives elite CEOs the edge. Our job is to ensure that our clients can fully focus on their families and businesses without the burden of everyday tasks. But what is everyday for someone else may not be for you. We provide comprehensive support tailored to your unique needs, making us the indispensable partner you never knew you needed.

Global concierge services: Imagine having your own personal concierge, dedicated to managing every detail of your life. From travel arrangements to event planning, The Life Curators are experts at providing bespoke solutions. Need to book a last-minute flight to a business meeting or plan an unforgettable family vacation? We’ve got it covered. Our global concierge services guarantee you peace of mind, knowing that every aspect of your life is in capable hands.

Personal assistance: Our personal assistance services are designed to give you back precious hours in your day. We handle tasks such as grocery shopping or gift purchasing. This allows you to spend more quality time with your family and focus on the things that truly matter.

Executive assistance: Running a successful business requires unwavering commitment and dedication. With our executive assistance services, we become an extension of your team, ensuring that administrative and operational tasks are efficiently managed. Whether it’s scheduling meetings, handling correspondence, or streamlining processes, our team of experts is here to lighten your workload, allowing you to steer your business to new heights.

Strategic advice: Achieving the perfect work-life balance often requires a strategic approach. The Life Curators offer personalised strategic advisory services that align your life and career goals, ensuring that both aspects flourish. Our experts help you set clear objectives, establish efficient routines, and implement strategies to optimise your daily life.

Wellness and lifestyle enhancement: Life isn’t just about work and tasks; it’s about enjoying every moment to its fullest. Our team includes wellness and lifestyle experts who can guide you in making healthier choices, enhancing your overall wellbeing and ensuring that you experience all that life has to offer. From fitness routines to travel experiences, we curate a life that’s both successful and deeply satisfying.

True assistance makes the difference

Every individual and business is unique, and it’s a smart move to consider how outsourcing services like these can help you regain control of your life. Tailored solutions are a must, ensuring a highly personalised experience that caters to your specific needs and preferences. Global reach is crucial too, so insist on an international network to ensure you’re always connected to a trusted team. The most precious resource we offer is time, and regaining hours in your day means time spent with family or devoted to growing your business. With that comes peace of mind and the knowledge that your life is meticulously managed, allowing you to focus on what truly matters. The Life Curators team offers all of this and more, even down to putting a number on how many hours a week our clients can win back by partnering with us.

Achieving the perfect work-life balance often requires a strategic approach

Peace of mind for meaningful moments

More and more executives are making the choice to have The Life Curators by their side and experience the freedom to concentrate on what truly matters to them. The ultimate goal is to empower you to not only succeed in your career but also flourish in your personal life. Elite-level assistance is no longer simply getting the admin done; it is the key to unlocking a life where both professional and personal aspirations thrive in equal importance. Support from concierge, personal and executive assistants, strategic advisors, and even wellness experts and crisis managers means that now you can redefine what success means and attain it. Everyone wants a more fulfilling, balanced, and prosperous life, and with your time on the line, it’s not just about efficiency; it’s about making every moment count.

Sustainability is a top priority for companies in today’s business landscape. In our pursuit to be as transparent as glass, BA Glass has a well-established sustainability strategy that has been part of its organisational culture for over 20 years. A sustainability strategy that is based on six key pillars – people, social accountability, shareholders, environment, consumers and customers – which strengthen and motivate us daily, to do more and to never stop trying new things, driving us to set and meet ambitious targets.

Our sustainability journey starts with the very essence of what we produce: glass. As glass container producers, we embrace the time-honoured human tradition of glass, driven by its unique properties: non-polluting, non-deforesting, inert, non-contaminating, reusable, and infinitely recyclable. This ambitious strategy has guided us to be the only glass packaging company to reach the highest score – an A – in the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), joining a group of only 299 companies in the world. CDP is a not-for-profit organisation that runs the global disclosure system across value chains to manage their environmental impacts.

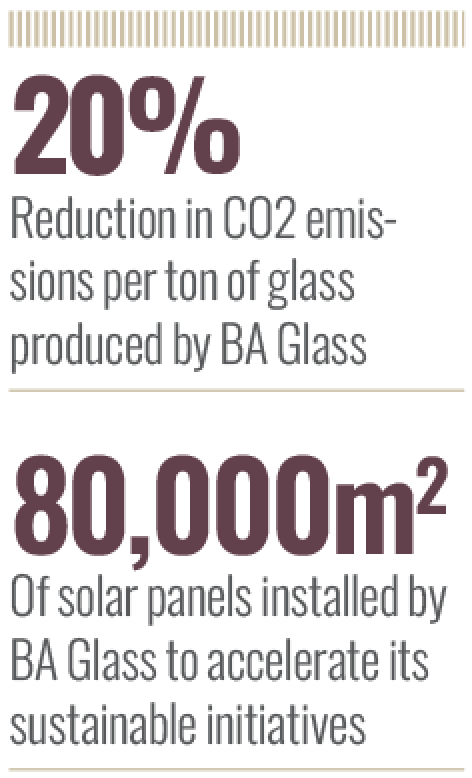

In 2020, we set an ambitious target of reducing CO2 emissions by 50 percent (scope one and two) until 2035 and received its official approval from the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), a prominent organisation that promotes the establishment of ambitious science-based emission reduction targets, in accordance with the Paris Agreement. In just two years, we decreased by 20 percent the CO2 emissions per ton of glass produced, in direct and indirect emissions, scope one and two. With a clear vision for reducing our carbon footprint, we have embraced numerous actions and initiatives, namely the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy sources. This energy shift was notably accelerated by the installation of 80,000 m2 of solar panels, resulting in a significant reduction of more than 4,100 tons of CO2 emissions every year.

The integration of cullet (recycled glass) into our production process represents a significant part of our ongoing efforts to minimise our environmental impact. Thanks to its characteristics, glass is 100 percent recyclable, forever. It can be incorporated into the production of new glass containers without any loss of its original qualities. This not only reduces the need for additional raw materials, but also leads to substantial reductions in CO2 emissions. We embraced numerous initiatives to increase the glass collection in all the countries in which we have production facilities, aiming to reach a 90 percent collection rate, a powerful initiative under the Close the Glass Loop, driven by the European Glass Association where BA has two board seats. Aside from recycled glass, another crucial aspect of our strategy is the reduction in weight of bottles and jars, which directly impacts our carbon footprint. In 2022, our innovative lightweight designs led to an impressive reduction of 2,500 tons of CO2 emissions (scope one and two), significantly minimising our environmental impact. Two years ago, we launched PURE, our sustainable brand.

PURE was created with the aim of making glass more environmentally friendly through conscious design, where nature comes first in every part of the creation process. As a result, we are challenging customers and brand owners to review their options on packaging design, embracing more sustainable options. Although our emissions in scope one and two are higher than in scope three, we are also devoting resources to reduce indirect emissions. Many initiatives with transport companies are being developed, and we are very optimistic concerning the significant CO2 reductions ahead. We are partnering with our suppliers in this common journey, debating their carbon reduction action plans and remain willing to actively participate in their initiatives. All these accomplishments, on our journey to be more sustainable, were possible due to the support of our shareholders.

Over the last three years, they have allocated €22m specifically for the development of technologies aimed at reducing emissions and minimising environmental impact. An example is the development of the ECO Furnace, an innovative new technology that will allow us to reduce the use of gas by green energies. This substantial investment in R&D projects underscores their dedication to driving positive change and securing a sustainable future. Besides the environmental concerns, BA’s sustainability journey goes beyond environmental responsibility. We aim to foster a positive impact on our employees and the communities where we operate. Our top priority is to empower our people by going beyond what we produce, creating career opportunities and promoting the development of their skills, through training programmes and enriching experiences that enable individuals to take on new challenges and expand their thinking. Moreover, we are always seeking to create a positive impact within our communities. Our ‘Glass Seeds’ project aims to promote equal opportunities and meritocracy in our local communities through educational support.

For BA, sustainability goes far beyond the production of glass packaging. It is about having a green and sustainable mindset in every action we undertake. Through our long-term commitment and with an ambitious roadmap, we believe that we are not just envisioning a more sustainable future, we are actively shaping it, aiming to be as resilient and eco-friendly as the material we produce – glass!

Banco de Reservas de la República Dominicana, known as ‘the bank of all Dominicans,’ is at a pivotal moment in its history. Serving as a catalyst in the Dominican economy, the bank has a strong reputation for participating in activities that promote the sustainable development of the country’s main productive sectors, support its sports and culture, and protect the environment.

As part of the celebrations for our 82 years of service, Banreservas is proud to be opening a third representative office. Located in Miami, close to the Dominican Consulate, it will attract new business opportunities to the country as well as serving the Dominican diaspora. Our existing representative offices located in Madrid and New York, along with the new office in Miami, will allow Dominicans to access banking products and services managed from within the Dominican Republic.

These offices make Banreservas the only Dominican bank to go beyond its borders with an international presence in the US and Europe. They demonstrate our genuine interest in encouraging the economic growth of the nation and promoting the prosperity of all Dominicans, wherever they are.

The bank supports its clients to integrate ESG principles into their operations

Our digital strategy also supports these aims, with the Tu Banco app and website boasting 1.2 million active users as well as a monthly average of 7.2 million digital transactions recorded over the last five months.

We pride ourselves on our inclusivity and accessibility: our dual offices, launched in 2021, provide customers with an innovative combination of traditional and digital banking services, including the MIO electronic wallet. Digital account holders, meanwhile, can open a savings account directly in the app or online without having to visit a branch. This new feature saw 50,000 accounts opened in the first month following launch.

Our customer service chatbot, ‘ALMA,’ helps clients via WhatsApp, and our new Digital Token feature allows account holders to authorise transactions by generating unique and temporary codes to authenticate access. Banking with us is safer than ever as a result. Furthermore, we are the only bank in the country whose app doesn’t consume data – all Dominicans should have access to banking services, no matter their means.

Impressive results

2023 has seen an improvement in our financial performance thanks to strong leadership. The loan portfolio has grown by 15 percent, total deposits are up 18 percent and perceived profits are up 34 percent, from a year previously. Banreservas has achieved results that represent a milestone for the firm, our loan portfolio exceeding DOP$500,000, with a non-performing loan ratio of 0.73 percent (the lowest in our history). As of September 2023 our market share was 32 percent, making us one of the country’s leading financial institutions. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed opportunities for improvement in many aspects of the way we live. Continuing with the same patterns of production, energy and consumption is no longer viable – together we need to transform these habits into ones that will lead us along a path of sustainable, inclusive, long-term development.

Taking this into consideration, and wishing to achieve better risk management, since 2021 Banreservas has implemented an environmental and social risk management system (SARAS) whose purpose is to monitor environmental and social risks within our investment and credit activities. One of its main strategic objectives is to develop environmental and social awareness in the next generation in order to achieve a sustainable future. We do this in-house too: our internal Culture of Sustainability programme includes virtual workshops for raising awareness, training and empowering our employees in institutional sustainability.

We have been keenly aware of the importance of ESG since long before the pandemic, however. Since 2017 Banreservas has been part of the United Nations Global Pact, thereby committing to working towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), presenting an annual progress report on the adoption of sustainability in the company’s activities. In addition, Banreservas is an active member of the National Business Support Network for Environmental Protection (ECORED), using its online evaluation tool ‘IndicaRSE’ along with other international standards to ensure we are pushing forward with our sustainability agenda.

The bank promotes clean energy by offering loans for sustainable solutions

In 2007, the Dominican Republic passed legislation on renewable energy as part of its commitment to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by one-third by 2030. The main objective of this law was to increase the contribution of renewable energy sources in electricity generation to 25 percent by 2025. To comply with the legislation we launched ‘Renueva Verde Banreservas,’ a new financial service programme to facilitate families’ and companies’ switch to clean energy solutions. The programme is an invitation to incorporate environmentally friendly solutions at home and at work, offering financing of up to 80 percent of the value of the product, with fixed rates from 6.45 percent for up to three years, payable in installments of up to 84 months. Also available are partnership with businesses, financial education programmes, and special offers on products and services provided by companies in the Reservas family.

Together with its investment banking team, the bank supports its clients to integrate ESG principles into their operations, develop resilience and risk management and unlock new business opportunities in an evolving market landscape. Within its credit offer, the bank promotes clean energy by offering loans for sustainable solutions such as solar panels, hybrid and electric vehicles, scooters and electric bicycles.

We have also signed an agreement with Interenergy Systems Dominicana, a division of the InterEnergy Group and its Evergo technology platform, to install electric charging stations in the parking lots of our offices nationwide. We strive for energy efficiency in our own offices too, achieving power usage effectiveness indexes as low as 1.5 in our data centres.

As a result of all these initiatives, Banco de Reservas de la República Dominicana has been awarded 43 Sustainability 3Rs certifications by the Dominican Republic’s Center for Agricultural and Forestry Development. With most of the awards at gold level, we are the most recognised financial institution in the country in this regard, a sign of how seriously we take our responsibility of contributing to the country’s sustainability goals.

Supporting Dominican society

We contribute to the development of Dominican society through the work of our Sustainability and Social Responsibility Department. This work includes our focus on financial education and inclusion, which promotes a savings culture for sustainable economic wellbeing. Whether Dominicans are right at the beginning of their financial journeys or seeking financial rehabilitation, our financial education and culture workshops can help. The ‘Preserva’ programme, meanwhile, provides access to low-cost banking products aimed at promoting savings and good credit.

We support entrepreneurship through our ‘Cree Banreservas’ programme. It supports the sustainable development of innovative projects by Dominican entrepreneurs through specialised technical mentoring. Development of the productive sector is also key: the Banreservas ‘Coopera’ programme promotes the socio-economic development of national producers. It does so through the promotion of social projects for the production of goods and services located in vulnerable communities. Social inclusion is at the heart of the ‘Banreservas Accesible’ project too, promoting access to job opportunities within the Banreservas’ family for people with disabilities.

The bank carries out even more sustainability activities through ‘Voluntariado Banreservas,’ our solidarity and commitment programme. Plugging into two of the main focuses of the bank – social responsibility and sustainability, and human capital – it carries out community benefit projects covering areas as diverse as the environment, health, education and culture.

Looking to the future

Banreservas is dedicated to improving quality of life in the Dominican Republic through strategies that support the country’s long-term development. This is only possible through a combination of effective management of resources and prioritising the most vulnerable in society.

As a leading government-owned financial institution, we are well placed to compete with private banks to support the needs of our people.

Mitrade has dedicated its efforts in expanding its contract for difference (CFD) product range, reflecting its strong commitment to providing traders with an even more diverse and comprehensive set of trading products. This will benefit traders by offering them a one-stop trading platform to trade faster and smarter – capitalising on a wider array of market opportunities.

Mitrade is an Australian-based CFD broker that embarked on its journey in 2011 with a vision to revolutionise online trading. Over the years, it has emerged as a prominent global trading platform with over 2.4 million users, licensed by different regulatory bodies such as ASIC, CIMA, and FSC (Mauritius), catering to traders from around the globe. Offering an extensive selection of over 400 markets, Mitrade has become synonymous with unparalleled opportunities for traders to engage with a diverse array of financial instruments, spanning stocks, commodities, currencies, indices, and cryptocurrencies. Recognised as a popular trading app, Mitrade has garnered over a million installations across both Google Play and the iOS App Store. This extensive usage demonstrates the trust and preference traders have for this platform to meet their trading requirements. Currently, the trading platform is accessible through mobile applications, desktop, and web trader platforms.

Award-winning platform

Mitrade has established itself as a prominent global trading platform, continuously receiving acclaim as an award-winning entity from its early days up to the present moment. These accolades underline the platform’s dedication to offering outstanding services and innovative solutions to traders. Earlier this year, Mitrade received an award for ‘Best Multi-Asset Broker’ from World Finance. The award recognises Mitrade as the go-to platform for traders, allowing them to have an impressive selection of over 400 trading products such as forex, shares, commodities, indices and cryptocurrencies. By offering such a wide range of products, Mitrade makes it possible for traders to explore different markets and make investment decisions based on their preferences.

Top-picked trading products

Throughout the year, Mitrade has seen remarkable growth on its trading products. User favourites like NAS100, XAUUSD, AAPL, and EURUSD stand out for their exceptional performance in trading volume. Notably, VinFast Auto (VFS) shares have stood out among the new additions this year, constituting 2.8 percent of the total volume of US shares traded. With this widened scope, Mitrade is determined to elevate its offerings even further – Mitrade ensures traders have access to an extensive portfolio of assets, enabling them to diversify their investments and leverage a broader range of market movements.

We are committed to giving traders the edge they need in the fast-paced financial markets

Hassan Haidar, Head of Dealing at Mitrade, conveys his enthusiasm for the ongoing initiatives in launching new products, saying, “Mitrade is an all-in-one trading platform, crafted for traders of all levels, designed for ease of use and flexibility. We are committed to giving traders the edge they need in the fast-paced financial markets. This broadened range of CFD products, combined with our intuitive trading platform, underscores our steadfast promise to offer our clients diversification and flexibility.”

He goes on to express gratitude, saying, “I want to take this opportunity to extend a heartfelt thank you to all our users who have supported Mitrade on this incredible journey. Your feedback and support have been instrumental in shaping our platform into what it is today. We remain dedicated to continuously improving and innovating to meet your evolving needs. Your trust and loyalty are the driving forces behind our continuous efforts to enhance your trading experience. We look forward to many more milestones together.”

Low spreads and zero commission

In the world of financial markets, traders aim to maximise profits by leveraging advantages. Low spreads and zero commission fees are two critical elements that, when combined, create an environment empowering traders by reducing costs and increasing potential gains. Low spreads are pivotal because they directly influence the trades’ breakeven point and potential profitability. A narrow spread means lower initiation costs and a smaller movement required in the trader’s favour to turn a profit. This is especially vital for day traders and scalpers, for whom even small price movements can significantly impact profitability.

Mitrade’s offering of low spreads enhances the trading experience for their users, making them a competitive choice for traders seeking cost-effective solutions. Zero commissions on trades revolutionise online trading by removing the conventional fee structure associated with buying and selling financial instruments, benefiting traders of all levels. This reduction in trading costs is particularly advantageous for frequent traders and those with smaller capital. It also levels the playing field for beginners or those with limited funds, enabling them to learn and experiment without the worry of excessive expenses. Additionally, the absence of commission fees allows for more calculated risk management and encourages a dynamic trading approach.

This model promotes greater portfolio diversification, spreading risk and potentially enhancing overall success. For traders employing longer-term strategies, it allows them to hold positions without the pressure of ongoing fees. This transparency builds trust between traders and their chosen brokerage, eliminating potential conflicts of interest. In essence, zero commissions on trades provide a substantial advantage, streamlining trading for greater accessibility, efficiency, and transparency, while also giving brokerages a competitive edge in the market.

Revolutionising trading

With a focus on speed and efficiency, Mitrade has seamlessly integrated TradingView, a platform trusted by over 550 million users, into its trading interface. This integration brings a powerful set of tools to traders’ fingertips. They can now easily perform technical analysis, which involves studying historical price charts and patterns to make informed decisions about future price movements. This is a crucial aspect of trading, as it helps traders identify potential entry and exit points for their trades.

In addition, Mitrade’s comprehensive platform is bolstered by a suite of educational resources and analytical tools with an AI feature. One of the product highlights was MitradeGPT; an integrated version of ChatGPT and FXStreet news insights into the platform, making Mitrade the first in the CFD world to have this kind of feature. With MitradeGPT, users are able to access real-time insights, personalised guidance and a quick summary to navigate the complexities of financial markets – filtering out the noise from the bustling news environment. These recent product updates aim to equip traders with the knowledge and insights needed to make informed trading decisions. It encompasses market analysis, live webinars, tutorials, and a range of other resources designed to enhance traders’ skills and understanding of the financial markets.

Effective risk management is a cornerstone of successful trading, particularly in volatile market conditions. In any trading platform, when market fluctuations are swift, there’s a potential for losses to exceed your account balance rapidly, potentially resulting in a negative balance following a forced liquidation. To mitigate this risk, Mitrade offers a valuable feature known as negative balance protection.

This safeguard ensures that even if losses temporarily surpass your account balance, the platform will promptly reset it to zero. This feature provides traders with an extra layer of security and confidence, enabling them to navigate the markets with greater peace of mind. It underscores the platform’s commitment to creating a safe and supportive trading environment for all users.

All-in-one educational resource

This year, Mitrade has also revealed the expansion of Mitrade Academy’s educational resources in 10 languages. This launch shows Mitrade’s dedication to helping traders worldwide by giving them easy-to-understand learning materials in their native languages. By offering an extensive range of educational content, including tutorials and trading guides, in languages such as English, Spanish, Thai, Vietnamese, and more, Mitrade aims to break down language barriers and foster a more inclusive and informed trading community. Mitrade welcomes both existing and new clients to explore our all-in-one trading platform and discover how easy it is to manage multiple investments on a single platform. The company’s steadfast dedication to innovation, user-centricity, and educational empowerment distinguishes it as a leader in the trading industry.

Comprehensive trader support

Mitrade’s 24/5 multilingual local customer service is a testament to their commitment to providing tailored and accessible support to traders worldwide. With a team proficient in various languages, they ensure that assistance is available whenever traders need it, from Monday to Friday.

This localised approach means that traders can communicate in their preferred language, facilitating clearer and more effective resolutions to their queries or concerns. This personalised service not only fosters a stronger sense of trust and reliability but also reflects Mitrade’s dedication to creating a global trading environment that feels truly welcoming and inclusive for all.

With COP28 just around the corner, sustainability is undoubtedly front of mind for most organisations. The aviation industry is making extensive efforts to address the current climate challenge, reduce its carbon footprint and create more sustainable air travel options.

But how can airlines realistically reduce their environmental footprint? While we know that a plane will never be more sustainable than a train or an electric vehicle, Wizz Air is on a mission to become a pioneer in sustainable aviation and has already delivered on a number of important milestones in terms of its sustainability strategy.

Pioneering sustainable aviation

Wizz Air proudly holds the title of the most sustainable low-cost airline according to the World Finance Sustainability Awards, with the lowest carbon emissions intensity in Europe, if not the world.

In the fiscal year 2023, we achieved an impressive 53.8 grams of CO2 per passenger per kilometre, marking an 11 percent reduction compared to the previous fiscal year. This achievement is the lowest emissions intensity ever reported by Wizz Air in a single fiscal year. We are not just setting records; we are setting industry standards and leading by example.

One of the key drivers behind our sustainability success is our commitment to continuous fleet renewal and focus on technology and innovation available here and now. The latest Airbus A321neo aircraft we operate is significantly more fuel-efficient than previous generation aircraft. Wizz Air boasts one of the youngest fleets globally, with an average age of four years, well below the average fleet age of its major competitors, which is around 10 years. Not only does this benefit our environmental efforts by reducing emissions intensity, but it also enhances the passenger experience with quieter and more comfortable flights.

We also believe that consumer sentiment is changing – passengers are choosing low-cost airlines over traditional network carriers, who are unable to meet the same efficiencies or achieve the same carbon emission reduction results. Switching to fly with Wizz Air can reduce a passenger’s CO2 emissions by almost 50 percent compared to flying with legacy carriers.

Future fuel

One of the cornerstones of Wizz Air’s sustainability strategy is the integration of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). While we are working with Airbus on their zero-emissions hydrogen aircraft, which is 20–25 years away from now, we see SAF as a bridge between the present and a more sustainable aviation future, on top of fleet renewal and investments in operational efficiency. Although SAF holds immense potential to reduce carbon emissions by up to 80 percent over the fuel’s life cycle compared to using fossil jet fuel, we acknowledge the challenges it poses. Biofuels and e-fuels, while promising, have a limited supply, making them expensive and difficult to obtain.

Nevertheless, Wizz Air is actively addressing these challenges. We have forged partnerships and invested in SAF, both securing volumes for the mandates that are coming in 2025 in Europe and trying to help new technologies come to life.

We have four agreements in place with the world’s leading SAF producers, including Neste and OMV. We also made our first equity investment of £5m into Firefly, a UK-based biofuel company developing the technology to produce SAF from sewage sludge, and participated in a $50m investment in CleanJoule, a US-based company making biofuel from renewable agricultural residues and other waste biomass. These strategic alliances will not only help us secure a stable supply of SAF, but also drive innovation in this crucial area of sustainable aviation.

A brighter air travel outlook

There has been an upturn in passenger numbers following the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry is recovering and people are flying again. It is clear, now more than ever, that the path to a more sustainable aviation industry involves investing in new technologies and embracing innovation. While Wizz Air has given the freedom to travel to more and more people, it has also proven that growth and sustainability can be achieved simultaneously.

By investing in the latest technologies, embracing SAF, and working collaboratively with partners, regulators, and stakeholders, we are leading the charge towards more sustainable air travel. We support legislative initiatives that mandate SAF use and encourage governments to invest in its production to ensure appropriate supply for the demand that is foreseen. In that regard, the European Union is a standard setter in terms of global climate policy, and we welcome such regulatory approaches.

With our holistic approach to sustainability and continued focus on resource efficiency, we are confident we can contribute to the communities we serve and the planet whilst also lowering our cost structure, strengthening the trust of our customers, and improving access to capital over the long run.

Boardrooms have the innate power to change the future not only of companies but the overall economy. When it comes to fully utilising their power, diversity of opinion is the cornerstone of a successful, powerful board. For a board to have a holistic viewpoint, it is vital that under-represented parties are heard. In fact, the configuration of the board of directors has been a vital research topic in the corporate governance realm for many decades now. During the last few years, the literature in the corporate governance field explicitly stresses the importance of gender diversity in the boardroom.

Several jurisdictions have enacted gender quota legislations to mandate the appointment of female directors on corporate boards. Gender legislation endeavours to address the ethical aspect that female directors have been significantly under-represented despite equal competence. Indeed, the Norwegian government was a pioneer in this field since it was the first to establish a 40 percent female quota in 2003. There now seems to be a widespread recognition among both company boards and stakeholders in relation to the benefits that derive from diversity, especially with respect to gender.

Shockingly, in 1983, based on the 10-year growth rate of the ranks of women directors, Elgart forecast that it could take about 200 years for women to attain equal representation in top corporate boardrooms. While the corporate world grapples with the imperative of fostering gender diversity, one bank emerges as a beacon of progress: the Bank of Cyprus. At our bank, the balanced participation of women and men in the decision-making process is imperative to the fundamental principles of democracy and human rights. Its advanced initiatives in championing board gender diversity set a laudable benchmark in the corporate governance sphere. A closer examination reveals the nuanced strategies and deep-rooted ethos that make the bank a trailblazer.

The historical foundations of the Bank of Cyprus provide a lens though which one can comprehend its unwavering commitment to gender diversity. Founded in 1899, the bank has not just been a silent spectator but an active participant in the socio-economic metamorphoses unfolding within and beyond the borders of the jurisdiction. In tandem with the societal changes, the bank illustrated a proactive consciousness toward the changing dynamics of gender roles. As women in Cyprus and abroad began to carve out spaces in the corporate world gaining visibility and prominence, the Bank of Cyprus acknowledged the imperative to reflect these changes within its organisational structure and leadership. To this end, the bank adopted policies and practices with the aim of promoting gender inclusivity at board level. This was not merely a symbolic nod to the trends of the time but a robust commitment to cultivating an organisation where, not only do women participate, they also lead.

Real data: An exceptional record

Quantitative data provides compelling evidence of the pioneering spirit of the Bank of Cyprus in the field of gender diversity at board level. In fact, official data – released in the 2022 Corporate Governance Report of the Bank of Cyprus – demonstrate that the board is comprised of 40 percent female representation. This progress is a culmination of years of meticulously planned strategies, manifesting the genuine commitment of the bank to gender equality. The empirical data of Bank of Cyprus provided in terms of gender equality tells a tale of unwavering, sustained commitment that has been nurtured and strengthened over time. The 40 percent female representation stands even stronger against the background of official data released on the subject; according to the 2020 OECD Analytical Databases on Individual Multinationals and their Affiliates (ADIMA) women are severely under-represented. Indeed, women in accordance with the ADIMA make up only 16 percent of board members in the top 500 MNEs.

The triumph of the Bank of Cyprus is not coincidental; it is the result of a gamut of calibrated strategies. Through meticulously crafted policies, recruitment strategies, and professional development programmes tailored for women, the bank has actively sought not only to accommodate, but also actively promote and celebrate female leadership within its ranks. In fact the bank sets explicit diversity goals, which strictly adhere to quantifiable targets with the aim to provide clear direction for its diversity mission. Additionally, in the process of candidate selection for board position nominations, the bank official considers in their suitability processes the impact of a nomination of a board member on gender diversity.

Behind the business rationale

The rationale behind the gender diversity commitment of the Bank of Cyprus is supported by a plethora of research and evidence that detail the correlation between gender diversity and business performance. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, one of the key issues of the board composition debate has been board diversity. Extensive research has indicated that gender diversity in the boardroom will lead to innovative ideas, increased competitiveness and performance, as well as better decision-making. Indeed, diverse teams contribute to a richer brainstorming ecosystem, crucial for banking in the current age of constant innovation.

The balanced participation of women and men in the decision-making process is imperative

Board quality and board diversity are interconnected since a diverse board are less prone to ‘groupthink,’ which has been defined as a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ striving for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.

It has also been suggested by bulk literature on the subject that the presence of female directors on corporate boards significantly contributes to the efficiency of corporate governance and increased corporate reputation.

Further to the link between gender diversity at board level and increased governance performance as well as innovation galore, there is evidence to suggest boosted financial returns are linked to gender diversity on the board. The McKinsey research showed that “companies in the top quartile representation of women in executive committees perform significantly better than companies with no women at the top.” In fact, in a 2013 report issued by Ernst and Young it was underlined how gender diversity can aid the improvement in company results in terms of better average growth and a higher return on equity.

The diversity journey

The path of gender diversity on the board is a perpetual one as societal change does not remain stagnant and societal dynamics are fluid. Plans on the horizon include intensified mentorship drives, partnerships with academic entities to sculpt the next generation of female financial leaders, and rigorous training sessions to eliminate unconscious biases in hiring and promotions.

While statistics provide a compelling story, the path of the bank in the journey to gender diversity is more profound. This is just a start. At Bank of Cyprus, we believe that financial institutions should continually search for new ways to use their expertise to further empower investors and promote gender diversity at all levels of leadership around the world.

The 40 percent board gender diversity of the Bank of Cyprus is a testament to the institution’s ability to introspect, evolve, and lead. Gender diversity is not regarded by the bank as a mere box-ticking exercise. On the contrary, it is an intrinsic part of its ethos, a commitment to reflecting the society it serves, and a strategic imperative to ensure sustainable growth.

In the vast landscape of global banking, where institutions grapple with the challenge of genuine gender inclusion, the bank shines brilliantly, offering lessons, inspirations, and a roadmap for others to emulate. As the world continues to champion gender equality, it is institutions like the Bank of Cyprus that will be remembered not just for their business acumen but for their role in reshaping gender inequalities.

Spanning Belgium, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic, KBC is a banking and insurance group with some 42,000 employees and 12 million clients. We offer a wide range of products and services such as investment funds and discretionary management for all types of clients: retail, private banking, and wealth clients, and we aim to cater for the varying needs of all. At the core of our day-to-day motivation lies our motto: ‘Everyone invested all the time.’

KBC Asset Management acts as the group’s investment arm, working with 2.8 million retail and institutional investors, developing products for intra-group distribution and providing investment fund sales and advisory support.

Digital first with a human touch

We believe that investing is a healthy financial habit for everyone, and innovation allows us to keep clients feeling comfortable when investing and so keep them invested. We do this in a personalised yet efficient way – we are also embracing AI, which helps us to change the way we interact with our clients in all market segments. Our Solution Development team takes solutions from idea to launch and initiates changes and challenges to existing solutions to make sure they match our clients’ needs at all times. A talented team works together to ensure proper asset allocation in managed funds and portfolios. The Solution Support team offers clients direct investor support, providing personal, relevant, and up-to-date information, training, and after sales services, and it does this by putting digital channels first.

Making investing a healthy habit

We take every opportunity to introduce innovative solutions to fit our clients’ needs. Over the last 10 years, KBC Mobile – our award-winning mobile banking app – has evolved into an all-in-one platform that is now the gold standard. Our virtual assistant, ‘Kate,’ has been the logical next step in the digital client experience, helping clients navigate investment options on digital channels, where over half of KBC’s investment plans are now sold.

AI models help in stock picking and optimising fund portfolios

We also added a ‘turbo’ feature on our digital service: investing with your spare change. The principle is simple; each time a client pays with their debit card, KBC rounds up the amount to the nearest Euro and automatically invests it. The client invests their spare change and gains investment experience with no effort whatsoever. The ‘turbo’ can be accelerated by a factor of two or three, enabling the customer to put even more aside if they wish. They can also activate or deactivate the ‘turbo’ at any time in KBC Mobile.

Investment innovation

We have broadened our digital offer both for first time investors and customers who want to respond to the challenges of today and tomorrow.  Customers can invest in themes close to their heart via thematic investing in KBC Mobile, either periodically or as a lump sum.

Customers can invest in themes close to their heart via thematic investing in KBC Mobile, either periodically or as a lump sum.

This is done without any human assistance via personal portfolio advice by ‘Kate’ to keep clients feeling comfortable when investing. Our smart advisory engine, based on AI, screens portfolios held by private and wealth clients on a daily basis. It performs a detailed analysis of each portfolio based on different risk and return factors and proactively formulates personalised advice. It is an E2E process that also takes into account clients’ personal investment preferences.

By embracing AI in fund management, KBC can respond faster to market developments. AI models help in stock picking and optimising fund portfolios. This enables us to respond to market developments faster and more efficiently for our clients. Two of our funds are even managed by AI; a balanced fund whose asset allocation and asset classes are determined with the help of AI-controlled models, and an equity fund whose stock picking is done by AI.

Responsible investing for 31 years

Since our first launch in 1992, KBC has systematically strengthened its policy, considering society’s constantly changing expectations and growing insights. Credibility is a core value for us; therefore this is monitored by the Responsible Investing Advisory Board, which is completely independent of KBC and consists of leading academics from several universities.

We work hard every day to get – and keep – everyone invested by providing tools and products that make investing easy, personal, valuable, and reliable. Using the power of data, our key focuses are innovation and employee and client satisfaction. By focusing on digitisation and creating value for our customers in a sustainable way, investing truly is becoming accessible for everyone.

For over 30 years Postbank has worked with a clear strategic vision for the future and the sustainable growth of its business. The bank offers innovations for an excellent experience for its customers and employees, and it invests in a green future in line with its ESG strategy. The excellent consumer experience is an immutable part of the bank’s corporate policy.

Through the development and implementation of every high-tech solution and the provision of services with exceptional added value, the bank reaffirms its ambitions to be a key leader in the financial services market and its desire to be the bank that offers its customers innovative concepts and solutions combined with flexibility and efficiency. Postbank provides an excellent experience and personalised financial products and services to its current and future customers, combining the latest technologies with a tailored approach, and professional consultation.

Continued growth

Postbank will continue to grow and the acquisition of the Bulgarian branch of BNP Paribas Personal Finance in 2023 is another step towards expanding its market share and taking an even stronger and more stable position in the ‘big four’ of the banking sector. This acquisition allows Postbank not only to strengthen its position in the consumer lending segment, but also to enter into a promising and fast-growing market that Postbank is eager to further develop by offering many more products to both new and existing clients.

The bank has started replacing the vehicles from the company fleet with hybrid and electric ones

As a result of the deal, Postbank strengthens its leadership position in retail banking and now occupies second place in the consumer lending market, adding a new client base to its portfolio and acquiring a portfolio of over BGN960m (€491m) in consumer loans. It generates significant opportunities for cross-selling as well as implementing innovative digital solutions for client convenience. With the successful finalisation of the deal, a team of exceptional professionals with a proven level of expertise and strategic vision in banking joins the Postbank team.

A new brand revealed

With the first-of-its-kind conference ‘Retail Reload – powered by AI’, in November 2023, Postbank introduced its new brand, ‘PB Personal Finance by Postbank’, which officially became part of the leading financial institution in June 2023. The special event, organised in partnership with Mastercard Bulgaria, brought together over 250 representatives from leading companies. Alongside internationally renowned speakers, they discussed the latest trends and innovations in artificial intelligence in the retail business.

The addition of the new brand, ‘PB Personal Finance’, is not only part of Postbank’s strategic development as a systemically important bank, offering innovations and personalised financial solutions for the convenience of its customers, but also of great importance for Eurobank Group as it expands its operations into significant regional markets. Just a few months later, Postbank reported excellent results and solidified its leading position in the consumer lending market by offering financial products to more than 1.2 million customers and providing BGN6.9bn (€3.5bn) in loans to households. Under the new brand ‘PB Personal Finance by Postbank’, clients will continue to receive a variety of attractive products and fast services in order to fully meet their expectations and high demands. The creative approach and innovative ideas are deeply embedded in the values of both companies and this is the key to a new understanding of banking that is shared and will integrate into a new ‘Beyond Banking’ concept, providing more value and benefits to clients.

On the road to success

In 2023, the financial institution received over 20 prestigious national and international awards for its innovative products, services, and corporate social responsibility. Postbank received the highest global accolade, Top Employer for 2023, from the international independent Top Employers Institute. Following on from these outstanding results, the financial institution won the award for successful digital transformation in the Bank of the Year awards of the Bank of the Year Association.

Postbank has received a Baa3 long-term deposit rating with a positive outlook by the international rating agency Moody’s Investors Service. At the same time, the rating agency has assigned a Baa2 long-term rating for Counterparty Risk Ratings (CRR) to Postbank. The robust capitalisation, strong recurring profitability, and growing deposit base of Postbank have been thoroughly evaluated and reflected in Moody’s report. The agency highlights that the bank’s strong profitability also supports its ability to generate sufficient capital internally.

Such an assessment from a global agency like Moody’s is recognition of the effectiveness of the bank’s work, the high standards it maintains in its operations, and the even higher goals set and achieved together with its team. Postbank are delighted that its efforts have been recognised at the international level, which once again emphasises and supports the progress it is making towards a vision of being a systemic bank in the market, with a strong presence, strictly following a strategy of sustainable development and setting trends in the country’s banking sector.

Green ideas

Traditionally, the banking sector is engaged with the financing of activities, which are directly or indirectly related to the development of other spheres of the economy, with banks being key participants in the ‘green transformation.’ Postbank’s strategy is focused on sustainable financing through priority support for activities with low or net-zero footprints, including credits for renewable energy sources, as well as for energy efficiency. Over the past few years, the bank has taken significant steps and implemented valuable initiatives to demonstrate its readiness to play a key role in the transition to a low-carbon and sustainable economy on the way to achieving long-term national and global goals.

Postbank introduced a special ‘Eco Auto Loan’ for financing fully electric or plug-in hybrid cars under preferential terms for its customers and a green business loan, intended for companies with projects for improving the environment.

Postbank is steadily transitioning towards renewable energy sources

Regulators expect the bank to support the implementation of the Green Deal by introducing various incentives and requirements for its clients. At the same time, prudential requirements for assessing and managing the environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks to which it is exposed are tightening. This calls for flexibility and innovation and new approaches and ways of doing business. The good news is that Postbank is already working on this.

Green light for new opportunities

The bank’s ESG strategy is being developed in two directions – the first relates to the internal processes and everything the organisation does, while the second addresses the clients and what they do with the funds the bank lends them. For 11 years Postbank has been internally tracking three indicators – the carbon footprint of the energy consumed, the amount of water used and the volume of paper used, and thanks to the efforts made, a significant reduction has been achieved in all three indicators. Thanks to the photovoltaic power station in the head office, Postbank is steadily transitioning towards renewable energy sources. This photovoltaic power station has a total installed capacity of 388kWp and its operation could save around 173 tons of coal annually, with close to 205 tons of CO2 emissions avoided.

The introduction of environmentally friendly, recyclable materials in the improved bank premises, the installation of LED lighting, as well as the introduction of the latest generation of more efficient and environmentally friendly air conditioning systems, are just some of the sustainable actions taken by Postbank on the road to a green economy. The bank has started replacing the vehicles from the company fleet with hybrid and electric ones and has also built an installation for the required power supply on the territory of the head office.

Postbank will continue to transform and innovate, demonstrating its modern signature among financial institutions in Bulgaria and a rich portfolio of innovative financial solutions for the exceptional convenience of its customers and over 3,000 satisfied employees.

In August 2019, Greg Webb joined Travelport as Chief Executive Officer. The travel technology company, which powers bookings for hundreds of thousands of travel suppliers worldwide, had recently been taken private and was about to undergo a tremendous digital transformation with the intention of solving some of the biggest problems in travel retailing.

But then, in March 2020, the pandemic hit, and the global travel industry went from all-time highs to a low of only five percent of expected volumes overnight. While travel initially ground to a halt, the pandemic eventually amplified and accelerated the need for the industry to get modern. Webb used this time to streamline Travelport’s operations, doubling down on the company’s investment in technology to ensure its next-generation platform, Travelport+, was ready when travellers were.

A next-generation platform

Travelport+ is the only modern retailing platform built for travel agencies. It connects buyers (traditional travel agencies, online booking apps, corporate travel management companies, and more) and sellers of travel (airlines, hotels, trains, car rental companies, etc) through a single, independent marketplace. Similar to Amazon, Travelport+ eliminates back-end complexities that cause long, mind-numbing searches for the perfect hotel room or make it difficult to shop and compare flights or car rentals.

The company’s global presence brings a variety of cultures, opinions and ideas to the table daily

Consumers expect digital experiences to be intuitive, frictionless, and fast. Other businesses have pushed the boundaries of digital innovation, but the travel industry has lagged. According to research by Travelport, booking travel is often regarded as tedious as evaluating mortgage or car insurance options. In fact, on average, travellers visit 38 websites before they book a trip. The lack of price transparency, difficulty in comparison shopping and the feeling of hidden costs all further erode consumer trust.

Webb is keen to improve upon the lack of transparency in the travel industry and is a longtime advocate for greater industry collaboration. His focus on transparency extends to Travelport’s corporate culture as well, where he regularly prioritises all-company town hall meetings, direct weekly communication, and more.

Investment in technology

Travelport continues to evolve its modern retailing platform with enhanced tools and new solutions that are designed to be intuitive, frictionless and fast. Additionally, the company is always looking for new areas to expand into, and in March 2023, the company announced the acquisition of Deem, a leading corporate travel management platform. Deem shares a similar goal of modernising a complex industry, more specifically offering the corporate travel landscape a more customer-centric booking tool. Just five months after the acquisition, Travelport had fully integrated the Deem and Travelport+ platforms, allowing shared corporate travel customers to book and manage their work trips in the same way they would their personal trips. This means more self-service, intuitive recommendations, real-time updates and changes that can be made on the go.

Supportive and transparent leadership

Webb’s vision and strategic direction have been instrumental in driving Travelport’s growth. His passion for the travel industry and his commitment to excellence have made him an inspirational and respected leader in the sector. It has also made Travelport a company that continues to lead the industry.

The company takes pride in cultivating a diverse and inclusive workplace where employees are encouraged to think differently and try new things. Travelport is committed to equality, prioritising a work environment where all employees can confidently, and comfortably, share their opinions and challenge the norm. The company’s global presence brings a variety of cultures, opinions and ideas to the table daily, something Webb believes is vital to Travelport’s success.

Change is for the brave

Looking to the future, Travelport continues to be committed to simplifying the complexities of the travel industry by inventing new solutions where there currently are none. Webb and the Travelport team work with industry partners who share their passion for delivering exceptional experiences and creating best-in-class technological solutions. The company continues to invest in the latest advancements, such as cloud computing, data-driven intelligence, machine learning and AI capabilities. The result is a more efficient and personalised travel retailing experience, which will continue to drive the industry towards a bold new era.

As the digital movement takes the globe by storm and the influence of Gen Z grows stronger, there has been a fundamental shift in the preferences and choices of the average banking customer. Customers are prioritising convenience and untethered access to their essential services at all times and that is becoming a requirement rather than a choice. While the global banking industry was moving steadily towards digitalisation, the Covid-19 pandemic triggered a reality-shifting chain of events that catapulted developing technologies to the very top of the priority list for consideration.

It also compelled banks and financial institutions to invest heavily in developing reliable digital channels to retain and expand their customer base. Digital banks, or Neobanks, as they are also known, have several benefits over traditional banks, including full user-centricity, not to mention convenience, agility, and further-reaching financial inclusion, all at considerably lower costs than traditional banks.

The Covid-19 pandemic necessitated disruptive growth in the digital banking landscape, accelerating trends towards increased digital adoption, remote banking, contactless payments, and fintech innovation. Lockdowns and social distancing measures prompted a surge in demand for convenient and frictionless financial services, leading to the rapid adoption of digital banking solutions.

Financial institutions, including Neobanks, responded by enhancing their digital capabilities, focusing on digital onboarding, and collaborating with fintech companies to meet the evolving needs of consumers in a digital-first environment. This period also witnessed a heightened emphasis on security measures and an increased focus on financial wellness tools.

The changes brought about by the pandemic in the digital banking sector are expected to have a lasting impact. The shift towards digital channels is likely to endure, with consumers continuing to prioritise online and mobile banking for its convenience and efficiency. Remote work trends are expected to influence how individuals approach banking, fostering a preference for flexible, remote-friendly solutions.

Ongoing collaboration between traditional banks and banking technology providers is anticipated, driving sustained innovation in digital financial services. The emphasis on security, financial wellness, and broader digital transformation efforts within the financial industry are likely to persist, making digital banking a central and enduring aspect of the post-pandemic financial landscape.

What Neobanks can offer

Innovation is the hallmark of Neobanks, and there are new facets emerging every day, including cutting-edge technologies like AI and blockchain that are utilised to significantly improve customer experience and meet the demands of their daily lives. There is no doubt that the benefits of Neobanks far outweigh traditional banking when it comes to convenience, so much so that this is often the decisive factor in choosing one bank over its competition.

Another key appeal of Neobanks is the great reduction in costs to both the bank as well as the customer, featuring low and sometimes even zero fees for some basic services. This is very attractive to the cost-conscious customer and encourages them to browse more of the bank’s products and services and benefit from them. Agility is also a profound benefit of Neobanks, allowing for new technologies to easily integrate with the bank’s app at a fraction of the cost compared to traditional banks, with minimal service interruption.

The ICS BANKS award-winning digital banking platform is built from the ground up on an open backend structure and a rich catalogue of APIs to ensure it stays up to date with the latest technologies available, giving our clients the power to vigorously compete in today’s quick-paced market. Our powerful backend transactional system allows the bank to extend out-of-the-box retail and corporate products and services, enabling them to compete and grow their customer base beyond traditional banks.

Putting customers first

Today’s tech-savvy users have higher expectations from their banking providers, taking for granted everything from personalisation and security to cost-effectiveness and accessibility. With the growing trend of personalised banking and catered financial products, consumers are more inclined to go with the bank that best suits their situation and needs. Top of the list for consumers is a user-friendly experience via intuitive mobile apps and online platforms that simplify on-the-go banking transactions.

Another key draw is the transparency of the fee structure: small print is no longer an acceptable practice, and consumers are unwilling to make any commitments unless they know exactly where their money is going. Convenience and accessibility are also crucial, with consumers favouring Neobanks that provide features like mobile cheque depositing, online bill payments, 24/7 customer support, and most importantly, digital onboarding processes. This saves a lot of time – not to mention the excessive paperwork – required to open a bank account, making them the main driver in expanding financial inclusion. Some Neobanks go even further by incorporating social features, fostering a sense of community and shared financial experiences.

Security remains a top priority, with trust often placed in Neobanks that prioritise robust measures like two-factor authentication and advanced encryption. Ultimately, consumers seek assurances of reliability and stability, whilst considering factors such as the Neobank’s financial health, regulatory compliance, and history of dependable service. Neobanks that can meet these expectations are poised to attract and retain customers in a competitive market.

Neobanks encounter multifaceted challenges in the financial industry, and ICSFS, as a technology provider, offers tailored solutions to address these issues. ICSFS is a leading provider of modern banking and financial technology powered by a solid, agile, and digital banking platform as part of its DNA. Neobanks can form strategic partnerships with technology providers such as ICSFS to obtain expertise and solutions to navigate complex and evolving regulatory environments, improved security measures, revenue diversification, effective marketing, robust technology infrastructure, and leveraging data analytics technologies to enhance customer experiences.

The pressing need for robust cybersecurity measures is met through ICSFS, which delivers advanced security protocols, encryption methodologies, and regular security audits to safeguard Neobanks and build trust with customers. Privacy and security are also substantial concerns for Neobanks, with the increasing risk of data breaches and unauthorised access to sensitive information. To mitigate these security challenges, ICSFS has recently obtained the iSMS (Information Security Management System) ISO/IEC 27001 Standard Certification, addressing any possible vulnerabilities through periodic audits and adopting advanced technologies like biometrics for enhanced identity protection in addition to rigorous security protocols aimed at preventing cyber-attacks.

Furthermore, ICSFS supports Neobanks in their global expansion endeavours by developing solutions for cross-border services and compliance with international regulations, facilitating the seamless entry into new markets. In essence, the collaboration between Neobanks and technology providers like ICSFS plays a pivotal role in overcoming the dynamic challenges within the financial landscape. ICSFS is a one-stop-shop for Neobanks not only for its agile and future-proof technology platform, but also by offering a complete array of products and services that encompasses both retail and corporate banking services.

Enriching customer journeys

ICSFS launches innovative products that are constructed on a secured and agile integration on a single platform, such as ICS BANKS. This is a fully integrated end-to-end financial and banking software with many suites that future-proof business and financial activities, through a broad range of features and capabilities, with more agility and flexibility to enrich customers’ journey experience.

With the current digitisation storm and fast progress pace, ICSFS offers strong tools not just to make an impact, but also to be the leader. One of ICSFS’ strengths lies in its focus on the individual requirements and support for each of its clients.ICSFS offers agile and highly secure universal, digital, and Islamic core banking platforms with a multitude of modules and software products covering the entirety of banking activities from individual and retail banking to corporate, wholesale, agency and commercial banking, microfinance, finance leasing, investment and wealth management solutions. Its flagship banking solution, ICS BANKS, uses the latest industry-approved digital technologies to cover all of the banking business and offers a wide array of digital touchpoints to accommodate the fast-paced life of the banking consumer.

ICS BANKS banking software solution comes built in with a broad range of supporting products including powerful tools such as E-KYC and digital onboarding, blockchain technology, business intelligence, enterprise resource planning, document management system, management information systems, business processes management, payment systems, Islamic and conventional lending and trade finance, RegTech, credit facilities and risk management, investment and treasury, dynamic application and advice builder, in addition to a rich catalogue of open banking with APIs to ensure its flexibility for integration with the majority of available third-party fintech providers as part of its infrastructure, delivering high availability, scalability, low total cost of ownership (TCO), and impressive performance.ICSFS also aids Neobanks in achieving profitability by offering strategies for revenue diversification, minimising income leakage, assistance in expanding product portfolios, and optimising monetisation models. Recognising the reliance on technology, ICSFS offers scalable and secure infrastructure solutions, mitigating risks associated with system outages and cyber threats.

A hybrid future

The future of digital banking is marked by transformative trends and technological advancements. Key directions include the continued integration of advanced technologies, contributing to enhanced automation, personalisation, and security within digital banking processes. Open banking ecosystems are anticipated to foster greater collaboration, allowing seamless sharing of financial data through open banking and promoting innovation. Personalised and contextual banking experiences, service offerings that are expanded beyond traditional banking, and a focus on comprehensive financial ecosystems are expected to define the landscape. AI is profoundly influencing digital banking across various domains, transforming customer experiences and operational efficiency. In the realm of personalisation, AI leverages customer data to provide highly tailored experiences, offering personalised recommendations, targeted marketing, and customised financial advice.

While the trend towards digital banking is notable, it is unlikely that all banks will transition to a digital-only model in the near future. Factors including the diverse customer preferences, varying regulatory landscapes, and geographic considerations contribute to the continued coexistence of traditional and digital banking. Furthermore, some individuals still value in-person interactions and physical branches, particularly in regions with specific demographic characteristics or limited adoption of digital services. Regulatory frameworks also play a role, with certain jurisdictions mandating the presence of physical branches or setting specific standards for banking services.

Additionally, the diverse banking needs of customers and the challenges associated with a complete digital transition, including technological investments and organisational changes, contribute to the persistence of traditional banking models. Many banks are adopting hybrid approaches, combining digital and physical elements to cater to a broad range of customer preferences and needs. While digital transformation is a key focus for many institutions, the transition to digital-only banking is likely to be a gradual and complex process, varying across regions and institutions.

Contract for differences (CFD) trading has become increasingly popular for individuals wishing to participate in the financial markets. With worldwide popularity came increased competition, which quickly led to CFD brokers looking for cutting-edge solutions that could win over larger audiences. This article explores the trends either already emerging in the market or having a high probability of being adopted by industry players in the near future.

Integrated trading ecosystems

It is becoming evident that MetaTrader platforms, which have played a major role in CFD trading for a long time, are seeing an increase in competitors as major CFD brokers develop their own platform solutions. The events of September 2022, when MetaTrader platforms were banned from Apple’s app store, showed how dangerous it might be for brokers to rely on an external service provider for their main product. Although the apps were restored in the app store after a six-month ban, the concerns stayed, pushing many brokers to develop their own platforms for trading.

The task provided ample opportunities for innovation and rethinking of how trading platforms should work and what they should include. As a result, an industry-wide trend of integrated trading ecosystems has been developing. Such systems include everything a trader needs seamlessly incorporated into one platform.

One example of such a system is OctaTrader, developed by the international CFD broker OctaFX. This platform aims to integrate everything a trader needs in one seamless space where expert analytics, deposits and withdrawals, and profile management options, are all at hand. OctaTrader allows users to trade without any extra logins or app switches, helping them save time, which is especially important in the fast-paced financial markets.

The OctaTrader platform is available for mobile users using iOS and Android devices, as well as for web traders. Some of the extensive web trading functionality includes charts, the most popular indicators, technical analysis tools, multiple timeframes, and much more. The platform also has a multilingual user interface.

Launching its own trading platform was a major step forward for OctaFX as it allowed the firm to provide its clients with a single, comprehensive, and consistent trading system, which makes trading quicker and more efficient. To further enhance the trading experience, OctaFX is developing a unique hub with every kind of expert analytical information, which will be available for clients within the trading platform.

Artificial intelligence

Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) can potentially change the CFD trading industry. AI algorithms can analyse vast amounts of data and identify patterns and trends that may not be apparent to human traders. They can therefore be used to develop strategies and optimise portfolio management.

Traders can significantly improve their performance with forecasts powered by machine learning algorithms that adapt to changing market conditions while incorporating historical data. AI can assist traders in managing risk, which is a crucial aspect of trading. By analysing market volatility, AI algorithms can help traders set ‘stop loss’ orders and adjust position sizes based on predefined risk parameters. Additionally, AI can monitor the market in real time and alert traders to potential risks or anomalies that may impact their positions.

Launching its own trading platform was a major step forward for OctaFX

Another way traders can use AI is automated trade execution based on predefined rules and parameters. By removing human emotions and biases from the trading process, AI can enhance trade efficiency and improve overall trading performance. Considering the above, an AI assistant or advisor can become integral to any trading ecosystem.

Blockchain technology

Initially popularised by cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, blockchain technology has gained significant attention due to its potential to transform traditional processes and even whole industries. One of the key advantages of blockchain technology in CFD trading is enhanced transparency. Blockchain provides a decentralised and immutable ledger that records all transactions and interactions between the broker and the trader involved in the trading process. This transparency allows traders to verify the authenticity and accuracy of trade data, ensuring fair trading conditions and enhancing trust between the parties.

Blockchain technology offers several security features that can mitigate some of the risks associated with CFD trading. The decentralised nature of blockchain makes it highly resistant to hacking and fraud attempts. Each transaction on the blockchain is cryptographically secured and linked to previous transactions, making it virtually impossible to alter or manipulate trade data. This ensures that traders’ funds and personal information are protected from unauthorised access.

The transparency of the blockchain can offer some comprehensive opportunities for auditing in CFD trading. Since every transaction is recorded and stored on the blockchain, auditors and regulators can easily access this information and use it to monitor and investigate any cases they find suspicious. Additionally, blockchain-powered smart contracts can automate compliance processes, such as Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) checks, making it easier for traders to adhere to regulatory obligations.

Potential challenges