Banking in 2016

Financial institutions around the world face both obstacles and opportunities. How banks respond to these will define how they perform going forwards

It is now eight years on from the 2008 financial crisis. That date has already gone down in banking history as one of the most significant shocks to the global system since the Wall Street Crash. The ramifications of the shock are still being felt, while at the same time, banks – the world over, although to varying degrees – have also made great strides to rectify some of the weaknesses the crisis exposed.

From a global slowdown to unprecedented policies on interest rates, to the global glut in oil, to increased regulation, there are all sorts of squeezes banks have been feeling in 2016. Some (such as increased regulations) are in and of themselves good, while others (such as squeezes on profit margins) are blessings in disguise, which will make the world financial system leaner. At the same time, technology is increasingly offering new opportunities for banking products and innovation around the world.

Costly regulation

Most significantly, the Basel III framework, devised by the Basel Committee in 2010, aims to enhance capital requirement rules as well as phase in new liquidity regulations alongside new macro-prudential instruments. There has been continued delay for these new requirements’ full implementation, with the current date now being March 31, 2019. However, these new requirements for banks are pressing ahead, and all will feel the effect of implementation.

These reforms have already started to be felt among major banks around the world. In the European Union these rules have manifested themselves as the Capital Requirements Regulation and the Capital Requirements Directive IV. At the same time, the continent has seen the creation of a banking union. According to Dr Andreas Dombret, a member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank, in a special paper for the LSE Financial Markets Group Paper Series, “the reforms have actually worked.

Only the leanest will survive, but the global banking sector will be all the better for it

They have played a considerable part in stabilising the banking sector. Between 2008 and 2014 European banks have shrunk their balance sheets by 20 percent and have increased their capital ratios by five percentage points from less than nine percent to around 14 percent, where the latter has been achieved through reduced volumes of risk-weighted assets as well as increases in own funds”. The result of this is European banks’ balance sheets have been reduced and refinancing has become more sustainable.

All these regulations and more, while for the greater macroeconomic good, have been felt by banks’ profit lines. Curtailment of certain activities, along with the costs regulation compliance brings, has obviously acted as a drag on banking profits. Europe in particular has had a tough year. This is something banks will have to – and can – adapt to. Only the leanest will survive, but the global banking sector will be all the better for it.

Peer pressures

Compounding this is another trend: the rise of negative interest rates policy. Following the 2008 financial crisis, central banks around the world slashed interest rates in an attempt to stimulate lending and reboot their economies. With interest rates around the world now at record lows, attempts by central banks to further stimulate economies have resulted in what was once unthinkable happening: negative interest rates.

Across the world, central banks have opted for this unorthodox policy. In January, Japan’s central bank opted to become the first major central bank to try negative interest rates, while the ECB, Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland all followed suit, to varying degrees. This has raised concerns about the profitability of banks within Europe. Whether or not such policies will continue – or perhaps even deepen – is a key question facing banks today. At the same time, US banks are facing the prospect of seeing their lending rates rise, as further Federal Reserve rate rises are expected.

Click to enlarge

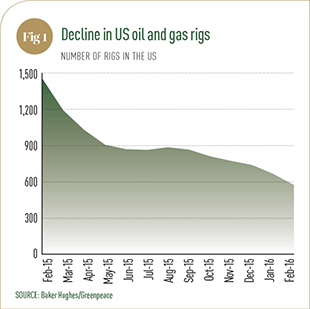

Click to enlargeOne issue that is likely to have an impact on banks is the fallout from the collapse in oil prices. Low prices have squeezed domestic US producers, who are laden with bank-financed debt. Having borrowed from banks at a time when the price of oil was high, two years of low oil prices have made many of these energy firms unprofitable. As a result, the loans lent to them by US banks have become increasingly unserviceable. As more shale (and some conventional) oil producing firms go bust (see Fig 1), those banks that lent generously to them in the era of low interest rates and high oil prices will feel a squeeze on their profit margins.

Moving over to China, banks in that region are also facing heavy pressure. A combination of low interest rates in the US and Europe pushing capital eastward, as well as China’s breakneck speed of growth, led to a huge build-up of corporate borrowing. Now the world’s second largest economy has slowed down, many of these loans have become non-performing. Financial stability is good in China at present, and looks unlikely to change any time soon, but banks in the country will have to factor in these losses moving forwards.

Full tech ahead

Banking is also set to face the challenges of so-called ‘disruption’ from Silicon Valley. Increasingly, a new generation of technology firms are looking towards building, improving and introducing new technologies to assist in finance. New technologies offer the possibilities of modifying and surpassing many banking roles and services that have been considered fundamental up until now: new payment technology offers to cut out middlemen, while high frequency trading has, and continues, to offer up the possibility of trading without any actual traders.

Now the world’s second largest economy has slowed down, many of these loans have become non-performing

This trader-less trading, through the use of algorithms, has created an untold number of benefits for financial institutions – increasing liquidity and efficiency among them – while also presenting challenges, such as volatility potentially leading to ‘flash crashes’. Being able to harness electronic trading’s power while balancing the risks will be a key aim of any bank going forward. The revolutionary new technology of blockchain – an open-ended yet encrypted electronic ledger – also offers new possibilities for maintaining transaction records with increased integrity and efficiency. Deloitte is decisively optimistic about the future prospects of blockchain: in a recent report it predicted that, by 2020, blockchain-based payment systems will have gained a significant transaction value.

Banks – of all stripes – collectively provide the essential infrastructure behind the functioning of the world economy. Therefore their good practice and endurance is vital to all. It is vital to ensure the banks of the world are making positive strides towards ensuring their best practice. World Finance’s Banking Awards 2016 list just some of the banks – and the people behind them – that have stood out in continuing to provide the good governance, practice and sustainability of the world’s financial system, while successfully navigating the various issues that have emerged in the system since 2008.