After months of agonising back-and-forth negotiations, Italy and the European Commission have finally come to an agreement on the country’s non-performing loans (NPLs). The deal will help to ease market pressure on the financial sector by unloading €350bn of ‘bad’ loans, with a government guarantee to reduce the risk of doing so. Amounting to around 17 percent of Italy’s total loans, NPLs have hindered the ability of banks to generate capital and new credit, threatening the strength of Italy’s economy.

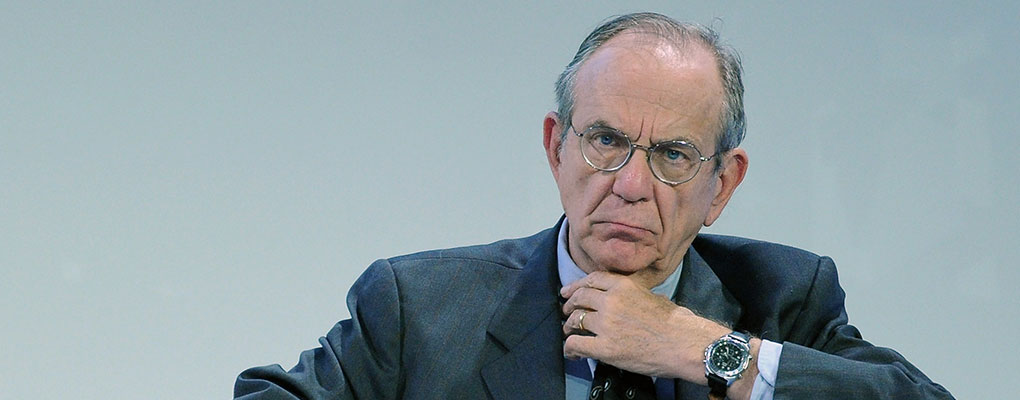

On 26 January, Italian Finance Minister, Pier Carlo Padoan, and Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner for Competition, held a meeting in Brussels to finalise the decision. Abiding by state aid laws, which prohibit favouritism or assistance that undermines competition, the deal introduced government guarantees that will facilitate the sale. The terms of the guarantees, which the banks can obtain by paying a fee to the government, are that they will only be provided for the safest loans. The guarantees also aim to incentivise investors to purchase the loan, with the government liable for the debt.

Bringing back profits

To prevent the guarantees from violating EU rules on state aid, Vestager insisted that the loans would be set no higher than market price. Furthermore, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance claimed that “this intervention will not create any burdens for our public finances”. The statement added, “The budget is neutral: in fact, the fees to be received are expected to be higher than costs and will therefore generate net revenues.”

After finally making the bad bank deal, there is renewed optimism between Italy and the European Commission. In an interview with Global Business, Padoan said, “This will bring back profits to banks. And as the economy grows more rapidly, this will reflect positively on banks, balance sheets and all of the economy.”

According to the Financial Times, Vestager commented, “Together with other reforms undertaken and planned by Italian authorities, it should further improve banks’ ability to lend to the real economy and drive economic growth.”

Their confidence in the deal isn’t unfounded: unloading these loans is essential in improving capital and economic growth. Before the deal was made, concerns over the bad loans hit capital markets, and the index of Italian banks was down nearly 25 percent since the start of the year. With the assistance of government guarantees, investors can rest assured that the debt will be sold at a higher price. The deal reduces the gap between what investors are willing to pay and what banks need to accumulate in order to avoid losses.

Too little, too late

However confident the Italian Finance Ministry and the European Commission are feeling, the deal isn’t without hurdles to be overcome. Filippo Alloatti, Senior Credit Analyst at Hermes, said, “The optimism part of my brain hopes this is the answer to some of the problems of Italian banks, but we have had false dawns in the past.”

The deal reduces the gap between what investors are willing to pay and what banks need to accumulate in order to avoid losses

Fabrizio Spagna, Managing Director at Axia Financial Research, said, “There are definitely advantages for the banks… but it is far from being the panacea for bad loans.”

One concern is that the deal doesn’t go far enough to allow the banks to recover. Previous efforts from those in Spain and Ireland forced banks to sell part or all of their bad loans at a set price to a government-backed bad bank, but Italy’s approach is more easy-going: the Wall Street Journal reported that a note from Citi analysts said, “The Italian scheme is a much lighter version, and as such it is likely to have a more muted impact on banks’ balance sheets.”

For instance, the government guarantee only covers the safest NPLs, and so analysts expect that the poorest-quality loans will remain largely unsold. If this is the case, this mechanism could later force banks to record sizable write-downs on their bad loan portfolios. Barclays’ analysts estimate that even with the guarantees, the six largest Italian banks could experience combined losses of between €6bn and €28bn.

Regardless of the speculation, Italy could not hold off on a decision any longer. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, other European countries, such as Spain, acted promptly, setting up bad banks to quickly remove soured loans from their balance sheets. Italy, however, felt that its banks were more robust and such measures were not necessary. Since then, NPLs have continued to pile up: according to research firm Imprese Lavoro, 75,000 firms went bust between 2009 and 2014, adding copious amounts of debt.

Changing landscape

The most common concern among analysts is not whether it’s the right approach, but whether it has been implemented too late. European countries that took action soon after the financial crisis were allowed more lenient economic policies in order to salvage their loans. In 2009, Ireland scooped bad credit off its banks’ balance sheets and into an asset management vehicle, and Spain followed suit in 2011, laying the foundations for stronger economic growth. Now the system in Europe has changed.

To prevent state aid that could effectively distort the market and competition, the European Commission is now taking a more severe approach: under new rules approved by the EU in 2013, shareholders and bondholders must bear the cost of bank failures before taxpayer money can be used in any rescue – including the creation of state-backed bad banks. Italy finds itself in a position that prohibits it from implementing the policies needed to recover the financial sector.

Last September, Padoan said, “Maybe this country realised a little late that something should have been done when European legislation still permitted it. The legislation on these things is much more restrictive since 2013, because of state aid rules.”