In a world where government budget surpluses are as rare as four-leaf clovers, Paraguay has been a bastion of stability, producing nine consecutive years of budget surpluses over the past 12 years. After its first budget deficit in a decade, in 2012, the newly elected government passed a fiscal ‘golden rule’ law in 2013, limiting budget deficits to no more than 1.5 percent of GDP. Since then, the government has been struggling to meet this newly self-imposed rule as the necessities of political compromises are colliding with a stagnant domestic consumption.

When economic growth slows down, the temptation is high to adopt corrective measures that can be expensive for a sovereign’s budget. The outcome of the current debate in the country of whether the government should loosen its fiscal policy to push consumption, while the economy is still expected to grow between 3.5 percent and four percent by the end of 2015, will be paramount for the long-term development of the country.

Over the past 600 years, when a sovereign’s debt was becoming too big and unbearable, only two options came invariably to the table: defaulting or declaring war

Paraguay has managed to build the foundations of its current growth story on the success of its private sector, not just agriculture, but also services and industries, while maintaining strict macro-economic ratios: budgets equilibrium, growing foreign reserves and low external debt levels. The legacy of the past 12 years of economic orthodoxy needs to be treated with care, even in the wake of a growing economic crisis within neighbouring Brazil and Argentina.

Much can be learnt from other countries, most of them ‘developed’, where a trend of burying an inconvenient ‘debt’ truth is gathering pace. For that small South American country which is searching for its own long-term recipe for economic stability, current western world budget experiences demonstrate the pitfalls that can seriously restrict governments’ management and governance when fiscal orthodoxy is abandoned altogether.

Paying debts

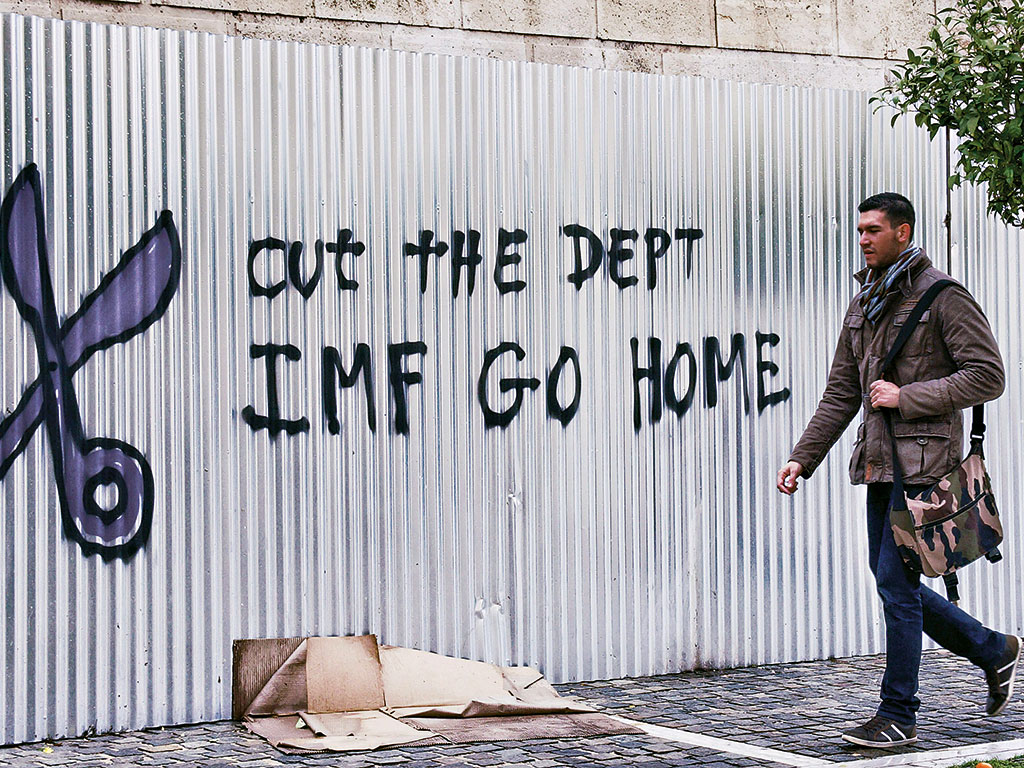

After years of twists and turns, the Greek tragedy is slowly coming to an end, and the question of weather sovereign debt needs to be repaid or not, needs a definitive answer. After more than five years of delaying the inevitable by, on the one hand, not taking necessary structural reforms to reduce public spending, and on the other hand, throwing more liquidity into a solvency problem, all that has been achieved is the doubling of the problem. Greece’s public debt that used to stand at 130 percent of GDP in 2010 is on course to reach close to 200 percent of GDP by the end of the year through a combination of rising debt and shrinking economy. The cake is now very large and the latest decision in early July to potentially provide additional life lines of up to $95bn is only going to make the indigestion worse, whichever final decision is taken. Death by a thousand cuts is never a good way to go.

One example that has been forgotten too fast and that should work to a certain extent, as a blueprint for future European (or other) debt crisis management, is the Icelandic case study. The country declared itself bankrupt in 2008 in the wake of the spreading global financial crisis. Immediately after, very tough measures to curb public spending were taken, in some cases cutting in half subsidies and salaries. Some two years later, the country was growing again (after a drop of 40 percent in its GDP) and three years after the beginning of the crisis, the country was able to return to the sovereign bond market with new 10-year bonds issued at less than six percent (much lower than some of Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain equivalent bonds at that time). An amazing success for a country that, at the peak of its financial bubble, had a financial system 15 times bigger than its economy.

There is no alternative in a zero interest rate, zero inflation environment, but to curb public spending when there is no more room to increase public revenues. One problem is the measure of such fiscal irresponsibility.

Almost all analysis of sovereign debt focuses on two key ratios: debt-to-GDP and fiscal deficit-to-GDP. The EU had decided in 1992 through the Maastricht Treaty, to set limits to these numbers, beyond which it would not be prudent to venture: 60 percent debt-to-GDP and no more than three percent budget deficit-to-GDP.

Ever since the financial crisis of 2007-08, governments in Europe have been struggling to get back within these parameters; indeed, very few have achieved reducing their public deficits (see Fig. 1), and none in southern Europe has achieved a meaningful reduction in its overall debt that would bring it back close to the 60 percent mark. However, the real magnitude of the problem is not properly caught by such ratios. Only a measure of the deficits compared to revenue can demonstrate the extent of the problem and reveal how little chance there is for a lot of countries to avoid a default in the near future.

In Greece, public deficits were between 15 percent and 23 percent of tax income, a situation that is clearly unsustainable as there is no more room for either tax increases or significant public spending cuts after six years of recession. The IMF, by asking for a debt restructuring that includes substantial ‘forgiving’ cuts, is highlighting this issue very clearly this issue.

That situation is widespread to varying degrees in Europe and needs immediate correction. There is only so much that a borrower can decide on his own until the lenders decide for him. That time has now come for Greece, but it will also come for other countries. France, Italy, Ireland, and so on, are not different cases; the spotlight is just not shining on them, as of yet.

The right track

What this means for Paraguay is that it needs to persist in its approach to reach full fiscal conservatism, reducing the weight of its fixed costs as a percentage of revenues, continue to combat tax evasion and keep its sight on percentages of budget surpluses or deficits against revenues and not GDP.

Managing state finances is much more about the flow than it is about the stock. When you can’t pay teachers or pensions at the end of the month, the size of your GDP matters not, only revenues do. Banks lend to companies and individuals based on their capacity to repay, or their cash flow, not based on their wealth. Why should this be different for sovereigns?

Only by measuring debt-to-public revenues and budget deficits-to-public revenues, one can truly assess the financial health of a sovereign state. Over the past 600 years, when a sovereign’s debt was becoming too big and unbearable, only two options came invariably to the table: defaulting or declaring war. Europe has worked very hard on its integration over the past 60 years to move away from the warpath, so if history were to repeat itself (and there is no reason to think otherwise) default seems unavoidable for some European countries.

European debt will not disappear by itself this time, as we have entered into a new prolonged period of low (or nil) inflation and very low growth where anything between one percent and two percent of growth would appear miraculous. Unless dramatic social changes occur in the EU, growth will be impaired by a lack of potential productivity gain. Combined with an ageing population, substantial growth will not come back for a long time and sovereign debt weight will only continue to increase.

A golden opportunity

Paraguay should observe very closely what is happening in Europe and in the US. Lessons can be learnt when a sovereign reaches a point of no-return, when the debt weight is such compared to its revenue potential that no political good intention can help anymore and brutal spending cuts, with their social implications, are the only way out, short of a default. Even if a third bailout is agreed for Greece, it is already too late for it to make a difference and default will occur anyhow within the next few months, as the room to manoeuvre for the Greek Government (irrespective of its political ideology) has completely disappeared.

The Paraguayan economy has been growing at an averaged five percent per year for the past 12 years within a fiscal conservatism that has allowed the country to see its credit rating being upgraded four times in the past five years. This converted into a new ability to raise sovereign debt on international markets that translated into $1.5bn raised over the past three years (first ever international bond issues). That newfound fame needs to be controlled and kept in line with the growth potential of the state revenues, especially in a country where the fiscal environment is so favourable.

Paraguay still enjoys a relatively clean sheet when it comes to fiscal policies. It should continue to protect it as its most precious asset, as it is eventually the key to long-term stability and development and without it, a government becomes powerless.