When Manmohan Singh was inaugurated as Prime Minister of India in 2004, the world expected him to oversee a period of rapid transformation, fuelled by breath-taking economic growth. Here was a man renowned for his economic acumen, clean from the corruption that had beset many of his predecessors, and with previous experience of running the country’s finances. Coupled with the vast potential India had and hopes that Singh would shred much of the country’s labyrinthine bureaucracy, many observers predicted the country would position itself as a more democratic rival to China and as one of the economic powerhouses of the world.

Fast-forward 10 years, however, and the impending departure of Singh is being greeted with many of the same calls for reform that were heard before his selection. While India has moved forward, the lacklustre pace at which it has happened has led to Singh being dubbed a disappointment of a leader who struggled to implement any meaningful change.

Now, as India heads to the polls once again, many people are hoping that voters will select a government with serious ambitions to radically overhaul the country’s economy. The signs are, if state elections are anything to go by, that Singh’s incumbent Congress Party could take a hefty drubbing at the hands of the right-leaning, pro-business, Hindu nationalist the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

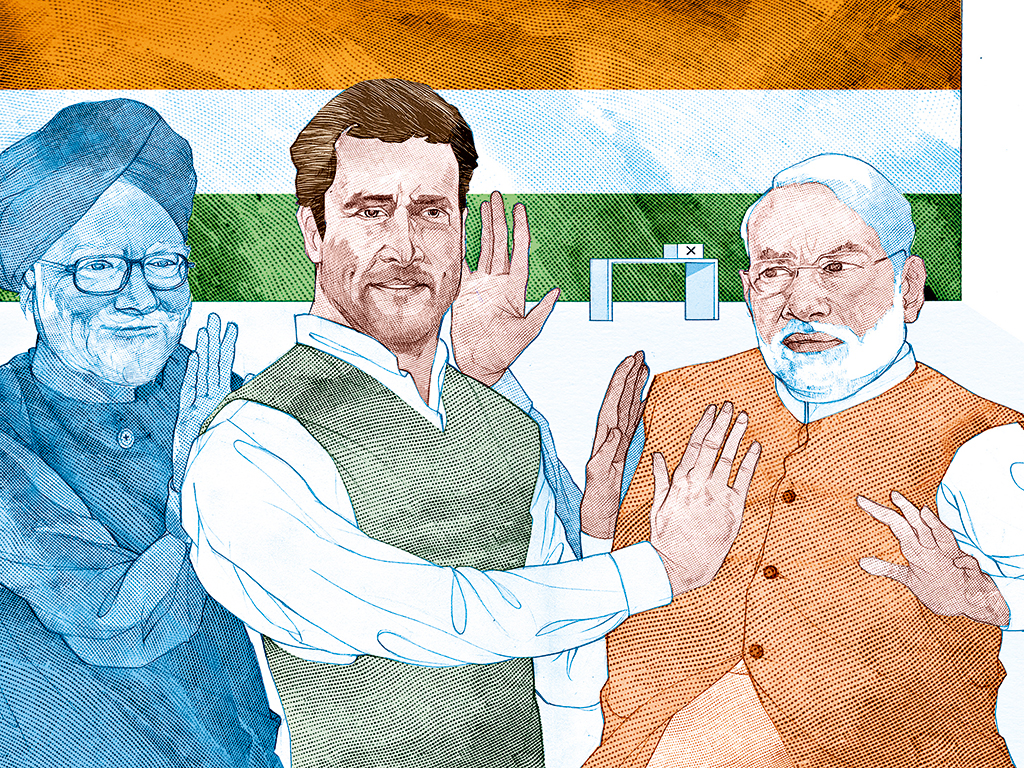

Recent opinion polls also suggest that the BJP, led by the charismatic Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi, are set to emerge as the country’s biggest party in May’s general election. However, the announcement of Singh’s intention to step down after the election has been seen as a sign that Congress know they need to do something radical to remain in power. Singh’s appointment of the young and dashing Rahul Gandhi, who just so happens to be a member of the prestigious Gandhi family that has dominated Indian politics since independence, suggests that Congress are looking to install some youthful vigour into the party.

The great-grandson of the country’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the 43-year-old Gandhi is known for his reticence when it comes to interviews. As part of his election campaign, however, he has started to appear before the media, something that many observers feel he’d do better to avoid. An awkward television debate with confrontational interviewer Arnab Goswani saw Gandhi come across vague and evasive, and disappointed his legions of supporters who expected him to capture the general public’s imagination with a charismatic performance. Others have accused him of being superficial and heavily reliant on his family history.

Divisive option

Modi, on the other hand, has successfully positioned himself as the candidate most likely to get the economy powering forward. International investors seem keen for a Modi-led BJP government emerging from the election, and ratings agency Moody’s predicts that such an outcome would see the economy improve on the estimated five percent GDP growth seen last year. Legendary US investor Jim Rogers has also backed him, telling Indian daily The Economic Times he could “make a difference”. “I hope Narendrah Modi brings some positive change in India. People like him can make a difference, and there might be a big stock market rally. But, in the last few decades, no Indian politician has made things better. The Indian currency is not fully convertible, and it is very difficult for foreigners to invest in Indian financial markets.” CLSA chief strategist Chris Wood also described Modi’s emergence as a candidate “the Indian stock market’s greatest hope”.

Congress know they need to do something radical to remain in power

While the world of international business may be eager to see a Modi victory, many Indians are vehemently opposed to the prospect of such an outcome. A hugely divisive figure on social and religious issues, Modi has been accused of wilfully allowing violence in the aftermath of Hindu pilgrims being burnt alive by a Muslim mob in 2002. Not a popular figure with Congress, Singh has said that the potential election of Modi as Prime Minister “would be disastrous for India.”

Cutting red tape

India’s economy is expected to have expanded around five percent over the last six months, remaining flat after 2012’s figures. The problems facing any new government will be how to cut the country’s famously prohibitive bureaucracy while halting the overflowing levels of corruption throughout society. It is also hoped that more will be done to encourage foreign investment, as well as solving the problem of soaring inflation.

The priority of any new government is to stabilise the rupee, while also making it easier for businesses to grow. The country desperately needs to do something to encourage foreign investment, something that it has been reluctant to accept for many years. In order to do so, however, it must seriously crack down on the rampant corruption throughout the country’s political and business communities, such as favourable contracts being given to family members that have little or no experience on the relevant projects.

Slashing the red tape that binds and trips up businesses throughout India is also essential. Singh’s government has started to do this with its recent backing of the Indian Financial Code that will simplify financial law, but this is merely the first step in a much bigger journey towards a business-friendly legal system.

There is also an urgent need for India to invest in its infrastructure – as there has been for decades. For all the talk of grand, transformative schemes, little has actually been done to bring the country up to speed with the rest of the world.

While five percent GDP growth is nothing to be sniffed at, in the context of what is expected of an economy with such potential, it is somewhat disappointing. Years of dithering by Manmohan Singh’s government may not have lost India a decade, but the country has certainly missed a huge opportunity over the last ten years to establish itself as an economic superpower. It is not too late, however, for the world’s largest democracy to sit amongst the world’s largest economies.