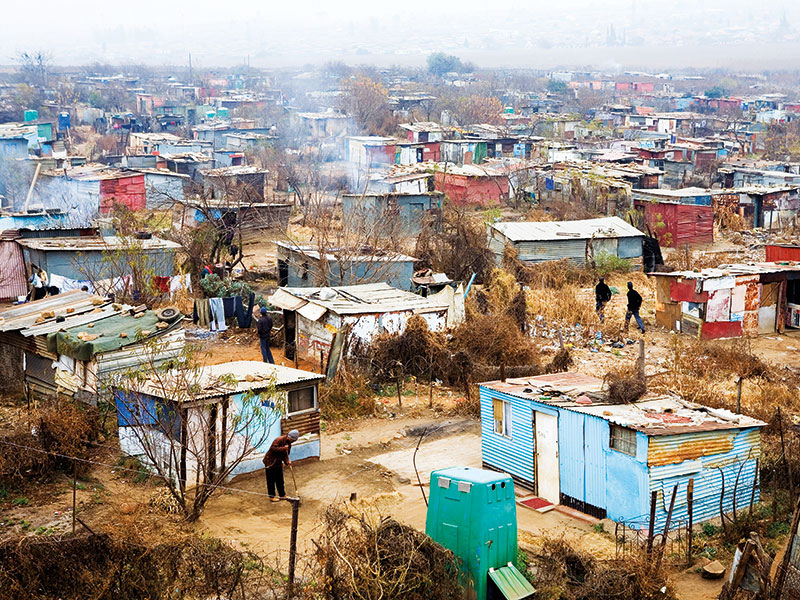

Unprecedented urbanisation has led to a serious shortage of affordable housing in cities around the world. In 2014, McKinsey & Company predicted that, if trends continued, as many as 1.6 billion people would live in substandard housing by 2025. African countries are among those currently grappling with this crisis – the continent’s housing deficit has not only been fuelled by urbanisation, but also by the growth of its vast population of young people.

Despite the problems facing the housing market, there is cause for optimism. Over the past decade, numerous developments have better equipped us to tackle this shortage: the rise of the sharing economy, for example, offers new solutions to the lack of affordable housing, while social media has empowered young people to voice their discontentment at being priced out of the market.

Governments have been slow to enact innovative housing policies unless forced to by crisis or dramatic change

Global warming, meanwhile, is driving the adoption of eco-friendly construction methods. Developments like this are set to have a significant impact on the industry and may even come to define the next decade of housing in Africa. For that to happen, though, the continent’s policymakers will have to be bolder and much more dynamic.

Shaky foundations

Housing policies in Africa are a hangover from the post-colonial era. Many of the major initiatives carried out on the continent were instigated by newly independent African nations and focused on mass housing – particularly for civil servants, who were usually the greatest contributors to the labour force and, therefore, the largest pool of voters. These policies reflected the conventional wisdom of the time, which suggested governments alone could stimulate demand and generate enough supply for housing.

Today, there is a constant battle between public sector intervention and private sector capacity. The right approach, as with most things, lies somewhere in the middle: public-private partnerships. The private sector neither has the will nor the incentive to take on affordable housing alone, and this is where the government must intervene. Governments, on the other hand, often lack the technical capacity or the systems to deliver affordable housing – areas in which the private sector excels.

Fortunately, there are signs that government policy in Africa is starting to catch up with this reality. The Big Four Action Plan – Kenya’s guiding social and economic development policy – has launched an ambitious affordable housing programme, bringing together both the private and public sectors. Equally, Morocco’s social housing programme has reported tremendous success, making it a key reference point for future study, while newly enacted tenant protection laws in Nigeria seem to be making good progress.

Unfortunately, governments have been slow to enact innovative policies unless forced to by crisis or dramatic change. Consequently, the push for more affordable housing will most likely have to come from elsewhere.

A global problem

This policy gap cannot and should not be construed as a problem unique to the Global South. The 2008 financial crisis was triggered by the mismanagement of the housing market and the exorbitant price of US homes. Alarmingly, the same trends that caused the crisis are still prevalent today: according to The Economist, real house prices have risen by 15 percent globally since their post-recession low, taking them well past their pre-crisis peak. As a result, there is mounting resentment among Millennials who are unable to get on the property ladder as easily as their parents did.

While a lack of affordable housing is a global problem, the challenge is especially pressing in Africa. The continent’s booming population is expected to almost double by 2030, surpassing 2.5 billion, according to the Brookings Institution. By 2050, the Mo Ibrahim Foundation expects more than half of the population to be under the age of 25.

Consequently, megacities such as Lagos, Cairo and Kinshasa – each of which already has a population of more than 10 million people – will continue to expand rapidly while other cities, such as Luanda and Johannesburg, will soon join their ranks. This population boom and rapid urbanisation is creating huge housing deficits: according to El-hadj M Bah, Issa Faye and Zekebweliwai F Geh’s open access book, Housing Market Dynamics in Africa, the continent’s housing backlog stood at roughly 51 million units in 2018. This is an urgent problem that African governments will soon be pressed to address. Over the next decade, numerous challenges could hasten government action.

Estate of mind

Housing has always been deeply political, but with the rise of technology – and its ability to coalesce people around a single idea – we can expect to see more social movements emerge in the coming years. It has already had a significant impact in the UK, with The Economist reporting that those who lived in areas with stagnant housing prices were more likely to vote ‘leave’ in the 2016 EU membership referendum.

The same was true of those who voted for the far-right National Rally party (then the National Front) in France in 2017. Housing prices have also added economic impetus to the protests in Hong Kong. Given the resentment of young people struggling to access real estate around the world, it is likely a global social movement or protests on housing will demand attention and action – Africa will not be exempt from this. Perhaps we are not so far away from a global #housing4all movement, after all.

Another trend starting to impact the housing sector is the emergence of the sharing economy. Platforms like Uber and Airbnb have demonstrated how technology can help us commoditise unused assets. There has been much talk of employing the rental model in Africa, and there is some merit to this idea: given the continent’s steep mortgage prices, it is more than likely that rental housing will remain a feature of the market. However, we may soon see some advancement in flexible living arrangements. In fact, shared spaces in which tenancy and ownership are not necessarily fixed-term are already beginning to take shape. The next decade will reveal just how sustainable this model is.

Already, the impact of human activity on our environment is becoming difficult to ignore – we’re seeing more heatwaves, flooding and uncontainable wildfires than ever before. These severe weather conditions have a direct impact on housing and how we develop infrastructure. While the housing industry has often toyed with the idea of using alternative building materials, the effect of climate change may force it – and government bodies – to accelerate the adoption of green innovations into building strategies.

It’s not just global warming we need to factor into our construction methods, though. The Ebola crisis that ravaged West Africa between 2013 and 2016 – and continues to rage through the Democratic Republic of the Congo – can also be viewed as a failure of housing policy. One of the reasons the contagion spread as quickly as it did is because of the density of housing in informal settlements. In the age of global epidemics, we will be compelled to consider how construction interplays with the environment beyond just the materials we use.

As safe as houses

Over the next decade, policymakers’ main challenge will be crafting a policy that not only addresses the aforementioned concerns, but also passes easily across African states. There have already been some positive steps in this direction. For example, the African Union Specialised Technical Committee on Public Service, Local Government, Urban Development and Decentralisation is pushing for a model law – an overarching legal and policy framework that all countries can adapt their national strategies to. This is informed by the recent conceptualisation of affordable housing as a human right.

Advocacy in the next decade is expected to be highly influential in pushing affordable housing to the top of the agenda. However, external forces – such as global warming, youth dissatisfaction, global crises and epidemics – may ultimately force African governments to reprioritise housing.

Technology could also play a pivotal role in alleviating the pressures that the housing sector faces. Africa has always tried to harness technology to leapfrog certain stages of economic development, and blockchain may help to transform the housing industry over the next decade, removing the need for intermediary players and streamlining the registration of property documents and other real estate processes. Smart contracts will be established entirely between the buyer and the seller (or, in this case, the renter and landlord) without requiring any human interaction.

The next 10 years will transform affordable housing in Africa. Admittedly, there is still much uncertainty – many things need to happen in order to drive change. Nonetheless, there are actions we can take today: investors, for instance, would do well to finance projects that benefit Africa’s youth, be it the construction of student housing, multipurpose buildings or rental homes. After all, Africa’s youth is its greatest resource – the best way to ensure a positive future is to invest in it.