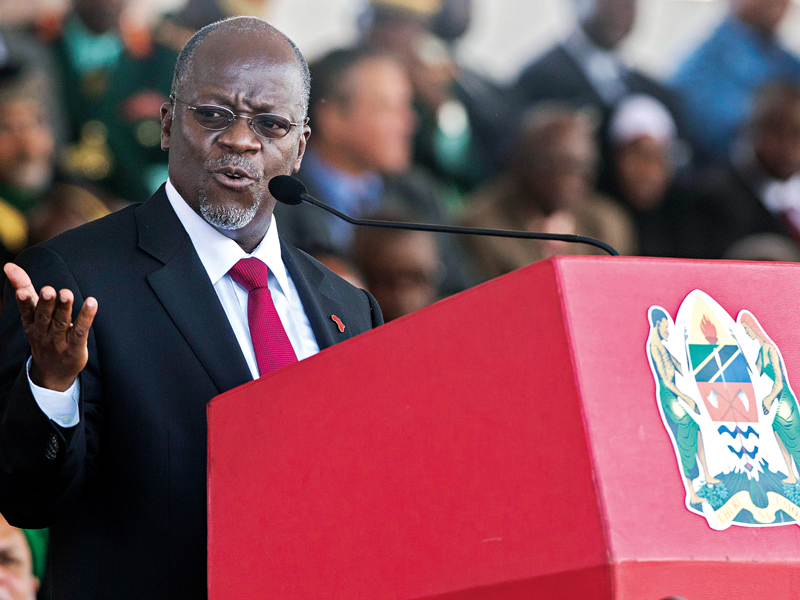

Ever since he was appointed Tanzania’s president in 2015, John Magufuli has pushed for much-needed industrialisation in the country. As the second-largest economy in the East African Community, Tanzania is often lauded for having huge untapped economic potential, but the country desperately needs to improve its transport links and increase its energy capacity if it is to boost commercial activity and unleash its potential. Magufuli has set himself a tight time frame in which to overhaul the country’s infrastructure, promising to have transformed Tanzania into a middle-income economy by 2025.

To achieve this ambitious goal, Magufuli is championing a number of major development projects. Between 2019 and 2020, the country plans to raise its total spending to $14.16bn, with the funds going towards improving the country’s infrastructure, while at the start of the year, the government revived the defunct Air Tanzania by injecting over $434m into the carrier’s fleet. Plans are also underway to construct another flyover for the Ubungo Interchange and to see the completion of the $14.2bn Tanzania Standard Gauge Railway, which will stretch 2,561km and connect the Dar es Salaam port to Rwanda and Burundi.

The Tanzanian Government has largely ignored the significant impact that the dam will have on the local area and the tourist industry

But the crowning jewel of these megaprojects is the planned construction of a 130m-high, 700m-long hydroelectric dam. According to the Tanzanian Government, the dam – which will be built in Stiegler’s Gorge in the Selous Game Reserve, an area renowned for its outstanding natural beauty – is projected to increase Tanzania’s total electricity capacity generation by 2,115MW. But the project is mired in controversy, with many fearing it could bankrupt the country.

A domino effect

As one of the last remaining great wildernesses in Africa, the Selous Game Reserve is home to some of the continent’s rarest animals, including the black rhinoceros and African wild dog. To build the dam, a 1,000sq km portion of the reserve will need to be stripped of vegetation. Shruti Suresh, Senior Wildlife Campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency, warns that this “will inundate a major part of the reserve and have a significant impact on the functioning of the Selous ecosystem”.

Unsurprisingly, news of the dam’s construction within the reserve’s borders has provoked international outrage. In a landmark move, UNESCO threatened to remove the Selous Reserve from its World Heritage List – something it has done only twice before. Meanwhile, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has condemned the project, calling it “fatally flawed” for its limited scope. “The current discussion is only focusing on the direct footprint of the dam and reservoir,” the IUCN said in a statement. “This is a dangerously narrow viewpoint as the impact will be much greater and far-reaching.”

According to independent research conducted by the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2017, the dam’s construction could have knock-on effects for the Rufiji-Mafia-Kilwa Marine Ramsar Site. Towns and communities in this area are dependent on the Rufiji River for fish; if the water supply to this area was to be diminished, the livelihoods of 200,000 people could be put at risk.

The dam is also likely to deliver a significant blow to Tanzania’s tourist industry: the majority of the one million tourists who visit Tanzania every year come for its wildlife safaris. It’s highly likely that, by destroying a huge expanse of the Selous Game Reserve and disrupting local wildlife, the region will see a dip in visitor numbers.

But the Tanzanian Government has largely ignored the significant impact the dam will have on the local area and the tourist industry. Usually, impact assessments help governments and developers to steer clear of heavy indirect costs – in fact, impact assessments are required under national law. However, in the case of the Stiegler’s Gorge project, none were carried out.

The closest the project got to a proper assessment was an analysis by the Consultancy Bureau of the University of Dar es Salaam, but experts in the industry consider this to be inadequate. This concern was highlighted by Joerg Hartmann, a consultant on hydropower sustainability, in his independent report on the dam’s feasibility. Hartmann wrote: “Compared to international good practice in hydropower, this is an unacceptably superficial level of information.”

Full steam ahead

Despite international bodies warning of unforeseen costs and even openly condemning the project, Tanzania is ploughing ahead. Magufuli maintains that it will become a linchpin of the country’s industrialisation. “Beginning today, this will indicate Tanzania is an independent country… and not a poor country,” he announced at the dam’s inauguration.

Yet Magufuli’s confidence has not appeased those who continue to question the project’s economic viability. Even without factoring in the indirect costs to tourism and local communities, the sum of money put aside for the project is considerable. In 2018, $307m was allocated for the dam’s construction, while the total cost of the dam is expected to reach $3.6bn, according to disgraced construction firm Odebrecht, which carried out the initial economic analysis.

Hartmann believes it could be even more than that, though, estimating that the project could cost the country closer to $9.85bn – almost triple what the Tanzanian Government has budgeted for. This would make it “the costliest investment in the history of Tanzania”, he wrote.

The government has promised that the dam will bring economic benefits – such as more employment opportunities – to the region, but this claim so far seems unsubstantiated. While Energy and Minerals Minister Medard Kalemani has announced the project will create 3,000 to 5,000 jobs, it is likely that many of these will simply go to the skilled engineers and labourers brought in by foreign construction companies, not to local citizens.

If the cost of construction overruns as much as Hartmann predicts, this will have wide-reaching implications for foreign direct investment in the country. The more indebted the Tanzanian Government becomes, the less willing investors will be to do business with the country, trapping the Tanzanian economy in a downward spiral rather than modernising it.

Bulldozing in

It could be argued that this is simply the price of industrialisation; there is no doubt that electrification would bring a much-needed economic boost to the country. Around 37 million Tanzanians have no access to mains electricity – a huge proportion in a country of 57 million. This hinders both its competitiveness and its attractiveness as an investment destination, with investors having long cited this lack of reliable power as one of the chief obstacles to doing business in Tanzania.

The new hydroelectric dam would change this, and could even help realise Magufuli’s ambition to boost the electrification rate to 90 percent by 2035. However, concerns have been raised over whether the dam will even be able to fulfil its core function: in his study, Hartmann uncovered that, without significant improvements to the country’s ageing power infrastructure, much of the energy generated by the dam would be unusable. “If Stiegler’s Gorge were to operate at full capacity, all other components of the Tanzanian grid would have to be approximately doubled to deliver the power to domestic consumers,” he wrote in his report.

What’s more, the dam might not even produce as much electricity as the government claims: its impressive 2,115MW figure comes from a feasibility study carried out more than 25 years ago. Since then, the river has shrunk by about 25 percent due to a number of severe droughts. With even its energy capacity being thrown into question, the dam looks increasingly like an unjustifiably expensive vanity project incapable of bringing the economic benefit the government promises.

Once one of Africa’s success stories, Tanzania is now in peril. Until recently, the country enjoyed relative political stability; each year, it attracted foreign direct investment worth an average of four percent of GDP. Now Magufuli is threatening to turn back the clock on decades of progress.

Nicknamed ‘the bulldozer’ for his forceful interventions, Magufuli has undermined Tanzania’s international standing throughout his tenure. In 2017, he accused Acacia, a London-listed mining company, of owing the country $190bn in unpaid taxes – a sum nearly four times Tanzania’s GDP. The company denies the allegation. Such bullish behaviour appears to have knocked investor confidence; the country has seen foreign direct investment more than halve since 2013 (see Fig 1).

He has also consistently undermined human rights in the country, with opposition politicians being shot and newspapers shut down. He recently drew widespread criticism for imprisoning the journalist Erick Kabendera as part of a concerted effort to limit press freedom. It has been made clear that critics of the dam will be silenced too. Kangi Lugola, the country’s minister for home affairs, said in a statement: “Those who are resisting the project will be jailed.”

The hydroelectric dam is an economic catastrophe waiting to happen. But it’s also a catastrophe of Magufuli’s own making; to back down now would be to admit defeat in his eyes. If the project does go ahead, the hydroelectric dam will indeed be part of Magufuli’s legacy, an homage to the relentless and single-minded way he drove the country – whether towards financial success or ruin remains to be seen.