Evidence for the use of plant-based psychoactive drugs can be found in texts spanning hundreds, if not thousands, of years. In book IX of Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus’s scouts eat what is described as the fruit of the lotus and experience not just a release from all their troubles, but a strong desire to remain where they are, absconding from all sense of duty on their return home from Troy. Over 2,000 years later, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, in which he documented his opium addiction following a bout of toothache while studying at Oxford, said of the drug, that it took him to a place where “the hopes which blossom in the paths of life” are “reconciled with the peace which is in the grave.” Since the ripe seed pod of the opium poppy “resembles the pod of the true lotus” according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, it is possible that both the people of ancient Mesopotamia and De Quincey were experiencing the effects of the same narcotic.

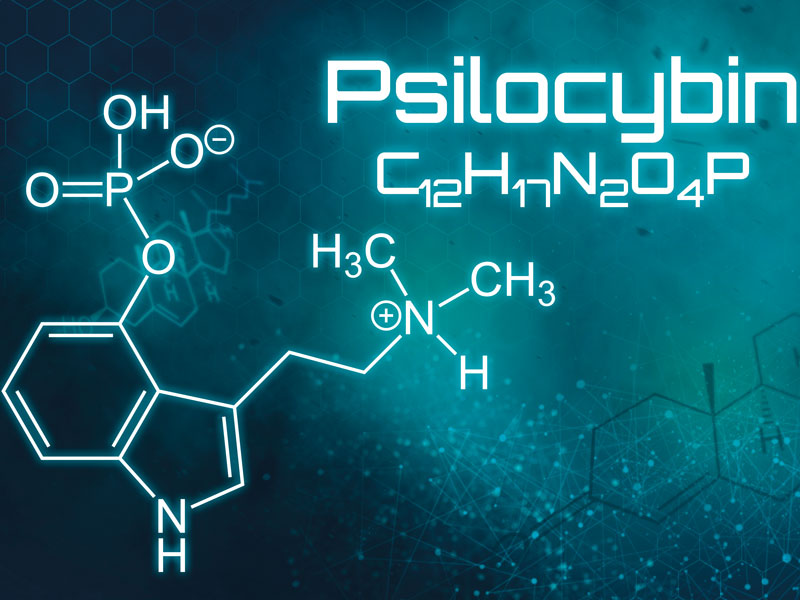

In 1970, President Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act, which labelled psychedelic drugs such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and Psilocybin (both of which can be derived from fungi) as Schedule I, which defines them as having ‘no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse’. Opium remains a Schedule II drug, the difference being that while still being highly prone to abuse it does have accepted medical uses. The act brought to an end a leading component of the counterculture movement of the 1960s and effectively closed the door on the psychedelic research that started with LSD in the 1940s and 1950s. The revival for research into the uses of those illicit Schedule I drugs began two decades later and it is only now that we are looking seriously at the potential for the regulation of administering psychedelics for the treatment of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Psychedelics are set to have a major impact on neuroscience and psychiatry in the coming years

In the past few years, clinical trials, such as those that have taken place at Imperial College London, and that involve testing the effects of synthetic forms of Psilocybin, MDMA and LSD, have increased in number as interest from scientists and investors alike has taken hold. What was once considered a scourge on society and what Nixon described as “public enemy number one” is now enjoying something of a renaissance in the field of psychiatry.

In April 2019, Imperial College London opened the world’s first Centre for Psychedelic Research. The centre is led by Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, who said of the opening: “This new Centre represents a watershed moment for psychedelic science; symbolic of its now mainstream recognition. Psychedelics are set to have a major impact on neuroscience and psychiatry in the coming years.”

Buying back in

The vaccine heroes of the global pandemic, AstraZeneca and Pfizer, among others within Big Pharma, were once more heavily invested in neuropharmacology, helping to bring antipsychotics to the market, which, coincidentally or not, coincided with the first revival of scientific interest in psychedelics in the 1990s.

Large pharmaceuticals may have shied away from central nervous system (CNS) drugs in the past, but according to a report by S&P Global referencing CB Insights, investment in CNS has been on the rise in the last decade: “The second fiscal quarter of 2019 saw $321m in funding toward mental health and wellness companies, a quarterly record for the therapeutic area.” I wonder whether the renewed interest in psychedelics will provide an investment path back into this broad area. Dr. Kaitin, a professor at Tufts University, is quoted in the report, saying: “A better drug for depression or psychosis, or the first real drug to treat Alzheimer’s, that’s going to be a mega, mega blockbuster.” The findings of clinical trials exploring the use of Psilocybin as an effective treatment for major depressive disorders (MDD) suggest that we might be quite close to this.

A research article titled The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010) by Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Pike and Kessler has estimated the economic burden of MDD in 2010 at $210.5bn, up from $173.2bn in 2005. This gives some indication of the effect of the 2008 global financial crisis, though of course this is difficult to quantify and one can only imagine what the global pandemic has done for our collective mental health. With MDD estimated to affect over 300 million people worldwide, it might be considered a pandemic within a pandemic. A report on the findings of a randomised clinical trial by Davis, Barrett and May entitled Effects of Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy on Major Depressive Disorder states that: “current pharmacotherapies for depression have variable efficacy and unwanted adverse effects. Novel antidepressants with rapid and sustained effects on mood and cognition could represent a breakthrough in the treatment of depression.”

I’m tempted to conclude that maybe the ancient Mesopotamians were on to something, though perhaps it would be wise to exercise caution. After all, De Quincey suffered with addiction for the rest of his life and Odysseus’s scouts had to be dragged back to their boats. But my concerns are less about regulation or abuse, and more about the mechanisms by which our brain chemistry is altered. As Kaitin said: “the crux of all this is, we don’t have an understanding of the basic mechanism… of a lot of diseases…there are no good models.” This is why continued research and renewed interest and investment from Big Pharma is so important, but I’m quietly optimistic that these new therapeutic drugs could be the mega blockbuster that MDD sufferers are looking for.