The feel-good news of this summer is that Greece has entered the final throes of its economic nightmare. The country’s beleaguered economy is finally showing signs of a turnaround, and a sense of optimism has tentatively returned. In 2017, the country witnessed three consecutive quarters of growth for the first time since 2006, while growth has surpassed expectations for several quarters. But most significantly, the start of this year saw a landmark decision from international creditors that the Greek Government has completed almost all of the necessary reforms, and is close to unlocking the final slice of bailout funding.

Despite evidence of a turnaround, the Greek unemployment rate remains above 20 percent and the costs of the crisis will be present for years to come

The decision puts an exit date in sight for the country’s painful string of bailout programmes. As World Finance goes to press, there is just €1bn ($1.23bn) of bailout funds that have yet to be transferred, out of the €266bn ($328bn) total in emergency funding that had been allocated over the course of all three of its international bailouts. If all goes to plan, the transfer will constitute the last disbursement of the fourth and final tranche of Greece’s third and final bailout programme, with August 2018 earmarked as the date when Greece will be free to fend for itself.

All parties hope that this will foreshadow a smooth return to the markets, signifying a resolute end to a drawn-out crisis. Indeed, throughout this saga, this moment has always been touted as the overarching goal.

But as the bailout exit date – or ‘Grexit’, as it’s inevitably been dubbed – gets closer, the country will have to prepare for life without regular chunks of low cost finance from its ‘troika’ of lenders, and will have to rely instead on financial markets. For a successful transition into post-bailout life, it will need to persuade the markets that its bonds are a viable investment and its businesses are worthy of international capital.

Breaking the chains

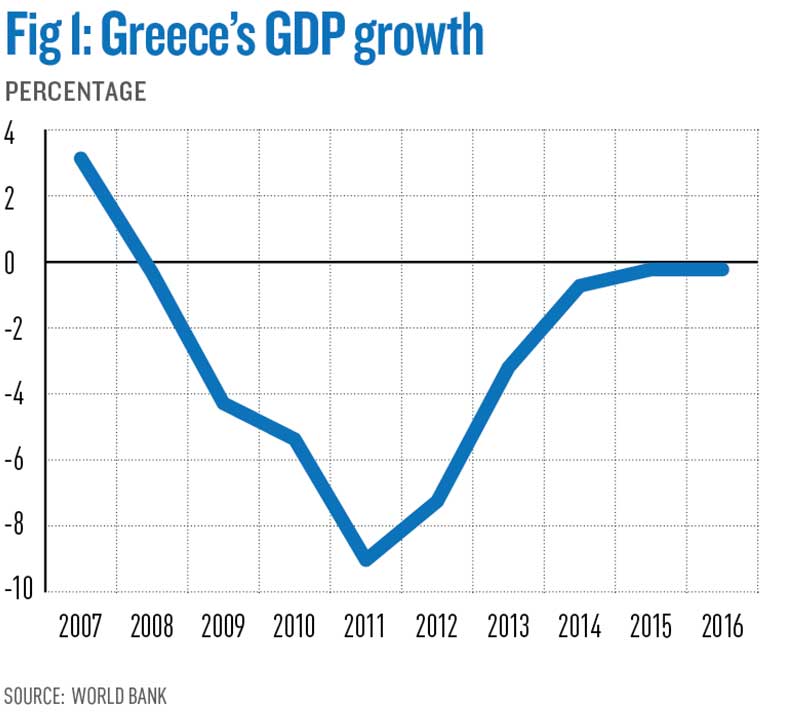

Merriment at the prospect of a bailout exit will be subdued for Greeks, whose economic fortunes were the biggest casualty of the euro crisis (see Fig 1). Despite evidence of a turnaround, the unemployment rate remains above 20 percent (see Fig 2) and the costs of the crisis will be present for years to come. Under its bailout arrangements, the government has pledged to run a budget surplus of three percent for 20 years, and a further bout of cuts to public services are yet to kick in. “There is a sense of relief that the economy has moved to some recovery. But, in itself, this is hardly a cause for celebration,” George Pagoulatos, a senior advisor to former Greek Prime Minister Lucas Papademos, told World Finance.

What’s more, as the date for Grexit approaches, the exact form it will take is far from clear, and there remains the pivotal question of whether European creditors will totally relinquish their grip on reform efforts and let Greece govern itself. Both the IMF and EU creditors are reluctant to let this happen, fearing that the Greek Government will roll back measures, including pension cuts and other efforts to improve productivity.

However, the Greek Prime Minister Alex Tsipras has promised a “clean” exit from the bailout process, suggesting that the country will be able to break free entirely from any conditions attached to loans from international creditors, and determine its own economic policy. But such rhetoric may stray from reality in this case: the prospect of returning to markets will be far from simple, as will the question of breaking free from the dominance of international creditors on matters of economic policy.

Keeping it clean

When it comes to a return to the markets, the initial signs are good. Eurostat forecasts project growth of 2.5 percent for both this year and the next. Meanwhile, the country’s embattled banks have begun to return to bond markets, with the National Bank of Greece turning to international credit markets in October for the first time in three years.

Improved investor sentiment is reflected in the continued decline in government bond yields, with the yield on benchmark 10-year bonds dropping to an eight-year low at the end of 2017. Yields have since remained low – if not stable – during the first part of this year, sitting at 4.4 percent as World Finance goes to press. In January, S&P Global Ratings raised its sovereign credit grade, while Fitch lifted its rating in February.

As post-bailout life approaches, Greece has moved to test bond markets. In order to convince markets that it will survive without bailout funding, the government has set out to build up a cash buffer and has plans to raise as much as €19bn ($23bn) in total through three bond sales before the cut-off date in August. In July of last year, it successfully entered bond markets for the first time since 2014. In February, it tapped bond markets for €3bn ($3.7bn) in seven-year bonds in an issuance that ended up being oversubscribed and achieving a 3.75 percent yield.

The IMF, which has until recently been issuing dystopian visions of Greek’s economic future, published a 192-page report late last year that stated: “The Greek economy has remained more resilient than expected in a difficult environment: fiscal targets have been widely outperformed, and game-changing structural reforms – in areas such as tax administration, the business environment, energy, privatisation and public administration – have been launched.”

Adding shine to the numbers

But a closer look will show that the prospect of a completely clean exit remains quixotic. For one, there is also a notable political spin to the language used surrounding the crisis: at this point in time, it is in many people’s interest to paint Greece as a success story. Speaking to World Finance, Dimitri Vayanos, Professor of Finance at the London School of Economics and editor of a book on Greek reform, observed: “[The Greek Government wants] to give something to the voters. The European governance wants to sell Greece as a success story. They want to be able to say that they have effectively applied an adjustment programme and as a result Greece has returned to growth. Both the European Government and the Greek Government have the same incentive to paint it this way.”

The effort to add shine to the situation is also reflected in growth figures by Eurostat. “Based on the current projections, Greece is forecast to grow the slowest out of all eurozone countries in 2017 – save Italy, which is very close,” Vayanos explained. Growth figures for 2017 depict growth in Greece at 1.6 percent, while the eurozone as a whole has grown by an average of 2.2 percent. Projections for the following years remain below the eurozone average. Vayanos notes that this is discouraging because, with unemployment at 20 percent and significant amounts of idle capital, the economy is already running far below full capacity and should be capable of more rapid growth than its peers. “There is a lot of room for growth just by getting the economy back to full capacity,” he said.

Several key figures, including Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras, have argued that a return to the markets will be messy without a ‘precautionary credit line’

In addition, several key figures, including Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras, have argued that a return to the markets will be messy without a ‘precautionary credit line’ from European creditors, which would act as a halfway house between a fourth bailout and a clean exit. This would enable the government to access more funds from European creditors in the case of a negative shock, with the goal of creating a buffer that would quell any market fears over the

fragility of recovery.

However, this scenario is unpopular with the Greek Government owing to the fact that it is likely to come with certain conditions attached, and this would disrupt any realistic chance of a ‘clean’ exit. Greek Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos has railed against the idea, arguing that there will be no need for a credit line when the country already has a cash buffer for the same purpose. “It would be stupid to have two buffers… No serious person would suggest both,” he said in a recent statement. “There may be stronger monitoring, as was the case in Portugal and Cyprus, but we will have much more freedom and we need to let the society know how we intend to use it.”

As clean as possible

In order to exit safely, there must be some confidence that the current recovery can be sustained, but there is no guarantee that this will be the case. In addition to its vast sovereign debt levels, which are approaching 200 percent of GDP, the Greek economy remains dogged by structural issues, a weak banking system, a drought of investment and the hangover effects of a painful depression. Deep scars have been left behind by more than eight years of flagging domestic demand, and the slump has triggered a punishing brain drain that has seen many of the most skilled members of the workforce seeking employment abroad. The exodus has been worst among the young, who for some time endured a youth unemployment rate of over 50 percent, though this has since dropped to around 42 percent.

The good news is that the budget deficit has now been reversed, after reform efforts acted to cut spending and improve tax revenue collection, and the trade deficit has been eliminated thanks to reduced consumption and a rise in tourism. But at the same time, productivity-enhancing reforms are yet to fulfil their promise, which is causing potential foreign investors to hold back. Vayanos explained: “There has been some progress. But much more needs to be done, and the growth prospects still aren’t good.”

Scars have been left behind by more than eight years of flagging domestic demand. The slump has triggered a brain drain that has seen many skilled workers seeking employment abroad

Reforms of the labour market and product markets, as well as a large-scale privatisation scheme, are still in full swing. “On the labour market, there has been some progress. The labour market has become more flexible. Firing costs have decreased and disincentives for part-time work have gone down as well,” Vayanos said. However, labour costs remain far higher than those in neighbouring countries, which could be reducing the speed of recovery. “The other issue is that there are high barriers to entry. Privatisation is happening, but there is not massive interest from foreign investors. More needs to be done to open up product markets and oligopoly,” Vayanos continued.

The justice system is also another source for concern for investors, with years of crisis taking their toll on Greek institutions. “There have been some efforts to make it more effective, but progress has been slow,” said Vayanos.

The ever-distant promise

It would therefore seem that the prospects for Greece’s future hinge, to a large degree, on the prospect of debt relief, which has consistently been touted as the reward that would be granted upon the successful completion of bailout programmes. The worry is that, with sovereign debt so high, it may be impossible for Greece to attract enough foreign and capital investment to break out of its depressed state. Negotiations have now begun in the context of Eurogroup meetings, which in itself is a significant step given that discussions into the details of debt relief have remained purposely vague throughout the bailout process.

The boundaries of debt relief were laid out in ambiguous terms last June in a statement from the Eurogroup. Critically, it will consist of debt reprofiling rather than debt restructuring, meaning that while maturities may be changed, there will be no overall debt reduction. They are also likely to include the transfer profits built up by the European Central Bank from its holdings of Greek bonds. The agreement also states that gross financial needs should not exceed 15 percent of GDP in the medium-term, post-bailout phase, and subsequently should stay below 20 percent.

While there is broad agreement that the vast size of Greek debt is a dead weight that is holding back its economy, divergences in opinion emerge over the future prospects of the Greek economy. The debate centres on the topic of debt sustainability, and the extent to which the debt load can be sustained without stifling any hint of growth.

Out of the total €320bn ($394bn) in debt, HSBC estimates that 80 percent is owed to the eurozone, meaning any debt relief is predominantly a question for European creditors rather than private lenders. The IMF, which holds a much smaller proportion of Greek debt, has long held that the debt will be unsustainable without meaningful relief from eurozone lenders. In fact, last year the fund went as far as suggesting that Greek debt will become “explosive” after 2030.

European creditors, however, tend to disagree with the IMF as to how the future might pan out, predicting instead that Greece will be able to shoulder higher debt levels. This difference in opinion is derived in part from the fact that, from the point of view of European creditors, any outright cut in Greek debt would be politically unpalatable, despite being practically desirable. Ultimately, a compromise may be found in which debt relief is linked in some way to growth, so that debt payments would decrease if growth rates disappoint.

The Greek economy will remain under surveillance for many years – if not decades – to come

The question of whether there will be conditions attached will be a key part of discussions looking ahead. Crucial to this debate is European institutions’ distinct lack of trust in the Greek Government: many of them suspect that the government will roll back reform measures once conditionality is dropped. There have also been talks of a ‘no backtrack’ clause forming part of an agreement, which would make debt relief conditional on the basis of the government seeing out the reforms that have already begun. This would act to assuage fears from the EU’s side, such as the commitment to a further round of pension cuts in January 2019 and a reduction in the tax-free income threshold in 2020.

“The best thing that [Greece] can hope for is an upfront reprofiling of the debt that would clear the way for the next years and decades to remove the fear that they might not be able to service the debt,” said Pagoulatos. “The less optimal scenario is a gradual, step-by-step form of debt reprofiling that will maintain uncertainty.”

A long road ahead

In any case, the Greek economy will remain under surveillance, according to the framework of the European Stability Mechanism, for many years – if not decades – to come. Under EU rules, post-bailout countries such as Spain and Portugal are monitored on a biannual basis by the European Stability Mechanism until 75 percent of their loans are repaid. In Greece’s case, current projections suggest that it will remain under surveillance until 2060, with other more pessimistic commentators predicting this time period could stretch on till 2100. During this time, the European Stability Mechanism will continue to issue reviews and potential corrective actions.

Asked if a clean exit for Greece is a realistic prospect, Pagoulatos said: “Continuity is stronger than rupture in this case, in the sense that, whatever the form of the programme framework, Greece will continue to be an economy under very close surveillance.” Ultimately, Greece is exiting the bailout phase of its economic saga, but the moment will not spell the end of economic suffering, and is unlikely to mark a sudden cut-off point in its relationship with its creditors. The relationship will change with optimism in the air, but the prospect of a final exit from the crisis still lies far ahead.