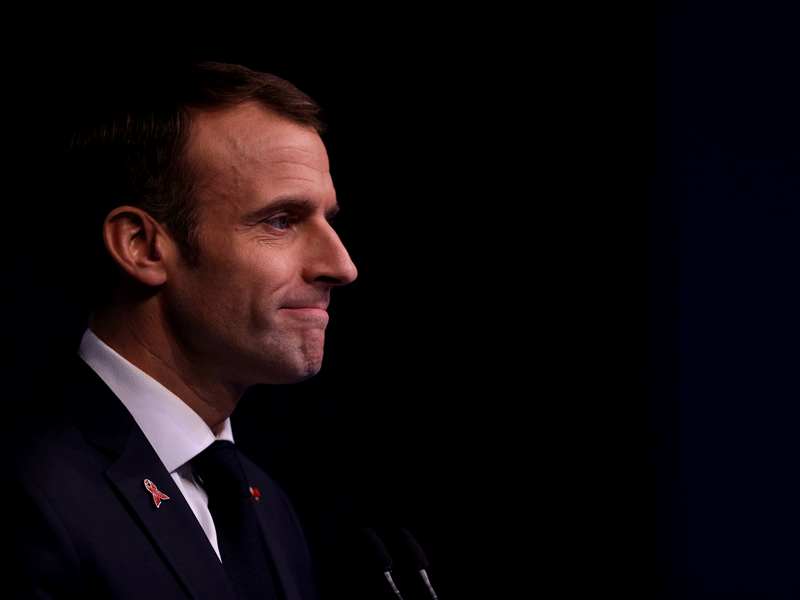

On December 2, French President Emmanuel Macron landed in Paris following the G20 summit in Buenos Aires contemplating the declaration of a state of emergency. Earlier that same day, flames engulfed the Avenue des Champs-Élysées as 36,000 disgruntled citizens took to the streets of central Paris.

Critics claim the tax will disproportionally hit those on low incomes living in rural areas

Heading straight to Avenue Kléber from the airport, a chorus of cheers and boos greeted the president as he observed the damage. Overturned cars, smashed shop windows and destroyed ATMs demonstrated the extent of the anger that has gripped the nation. For three weeks, the ‘gilets jaunes’ (yellow vests) have peacefully protested against Macron’s proposed fuel tax. The first weekend of December, however, saw the clashes turn violent: at least 412 arrests were made, while 263 people were injured and three others killed.

Shopkeepers had prepared for a fruitful weekend following the switch-on of the Champs-Élysées’s iconic Christmas lights, but were forced to close their doors as a battle between police and protestors ensued in the French capital.

Touted as the ‘president of the rich’, Macron’s pro-business reforms have been criticised by students and those on the political left as favouring the wealthy over the poor. During his brief presidential reign, protests and scandals have been a common occurrence. With a commanding majority in the National Assembly, opposition to En Marche! has taken to the streets.

The price of diesel, the most commonly used fuel in French vehicles, has risen 23 percent over the last 12 months. The fuel tax is part of an ambitious plan for France to become carbon neutral by 2050. The plan includes detailed commitments to end coal power by 2022, cease French oil and gas production by 2040 and a proposed ban on the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2040.

Critics claim the tax will disproportionally hit those on low incomes living in rural areas, who have no choice but to drive to work. With fuel prices at their highest level since the early 2000s, a proposed increase of 6.5 cents on diesel and 2.9 cents on petrol effective from January 1, 2019, was the tipping point.

Macron insisted he would never make a U-turn on policy because of street protests in an attempt to distance himself from former presidents. However, on this occasion, the substantial response has forced Macron to rethink his strategy. On December 4, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe announced the suspension of the tax for six months.

Growing inequality

Along with other developed or developing nations, income inequality has skyrocketed in France. With an estimated 8.8 million people living in poverty, the bottom 20 percent of the population earn almost five times less than the top 20 percent. “The problem for Macron is that this has moved so quickly from being a protest against fuel taxes to becoming a whole catalogue of social and economic grievances,” says James Shields, Professor of French Politics at the University of Warwick.

Unemployment has consistently stood above nine percent – one of the highest rates of any EU member state. Macron has pledged to cut this to seven percent within five years. One of the president’s first reforms was to make it easier for businesses to hire and fire staff.

Parisian technician Idir Ghanes told the Guardian: “We have low salaries and pay too much tax and the combination is creating more and more poverty. On the other side, there are government ministers and the president with their fabulous salaries.” He added: “I just want a fairer distribution of wealth in France. I’m unemployed; it’s harder and harder to find a job and, even when you find this famous job, the salaries are so low you find you’re in the same situation as before, if not worse.”

Macron’s anti-populist En Marche! movement, described as “neither left or right”, pledged to unite a divided nation following the 2017 presidential election. Elected as the country’s youngest ever president, Macron was seen as a slick operator, a Europhile who embraced tolerance and internationalism. What French citizens have found instead, is a lofty arrogance and an unwillingness to hear criticism of his reform agenda.“Opposition to Macron is partly about policy but also largely about style,” Shields explains.

Out of touch

As the former economy minister under his predecessor Francois Hollande, economic reforms became a key aspect of Macron’s 2017 presidential campaign. Having afforded an estimated €40bn ($44bn) in tax breaks during the last government, Macron pledged to continue reducing taxes when in office – corporation tax, for instance, will gradually be reduced to 25 percent.

France is famed for having one of the world’s largest public sectors, where 56.5 percent of GDP is allocated to public spending. A key manifesto pledge was to cut that spending by €60bn. When it was announced that €25bn worth of savings would result in the loss of 120,000 public sector jobs over the next five years, a one-day nationwide strike – involving millions of public sector workers and supported by all nine of the country’s public sector unions – represented the first sign of discontent.

GDP growth has remained steady in France since the 2009 financial crash, though the rate has rarely exceeded two percent. However, months of rail strikes earlier in the year caused growth to slump to 0.2 percent during the first two quarters of 2018. In September, it was announced that France would show a deficit of 2.8 percent next year, compared to 2.6 percent this year, due to slowing growth and Macron’s changing tax regime.

The ‘gilet jaunes’ – a reference to the high-visibility yellow clothing worn by protestors – is a grass-roots movement attributed to the French working-class. It has encompassed a wide range of participants: both the left and right have joined forces in their opposition. Surveys have revealed the vast majority of French citizens support the protests, while Macron’s approval rating has hit rock bottom, standing at just 26 percent.

Shields believes Macron has responded too slowly to this crisis, giving time for the protests to gain momentum and, crucially, for French public opinion to solidify in support of the protesters.His promise upon election, to use his five years in office to ensure that none of those who felt driven to vote for the extremes will have cause to do so again, is looking rather fragile.