Cracks in the system

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank in America and Swiss giant Credit Suisse raised the spectre that has haunted regulators ever since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008: Just how safe are the world’s banking giants and the global financial system?

As the evidence has shown in the months since, they are not as safe as we all thought. In the bigger picture the global financial system is under stress and in some regions is in turmoil, partly because of post-Covid inflation.

“Financial stability risks have increased rapidly as the resilience of the global financial system has been tested by higher inflation and fragmentation risks,” warned the International Monetary Fund in its latest Global Financial Stability Report issued in April 2023.

Some of the most vulnerable banks are in the smaller emerging economies where debt is high and the ability to repay is in decline. But overall the IMF sees a more desperate banking environment triggered by rising geo-political risks, unsustainable levels of debt, rising inflation and interest rates, and tighter money. Meantime it was a close-run thing, far closer than anybody was prepared to admit in those fraught few days of March. As Swiss Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter conceded in Washington in April, the lightning-quick, forced takeover of Credit Suisse by rival UBS “had helped to avoid a national crisis.”

And that’s just in Switzerland. The president of Switzerland’s central bank, Thomas Jordan, said the takeover had prevented Credit Suisse from becoming “the first domino in a systemic crisis.”

A systemic crisis! The immediate aftermath of the collapse of Credit Suisse and SVB revealed cracks in the system that must be rapidly repaired. As the news of the problems with the two banks broke, tremors ran through the entire finance sectors of Europe, the UK and the US. There were signs of distress through much of the financial sector in America, where two others banks collapsed in a classic example of contagion.

It’s not so much the failure of one bank that worries regulators; it’s the risk of contagion. It may seem unlikely that the failure of a second-tier bank like SVB on the other side of the world would further destabilise Credit Suisse, but that’s exactly what happened. Spooked by events in Silicon Valley, more depositors pulled their funds from the Swiss giant and accelerated its demise.

Although the Swiss authorities get full marks for moving quickly and decisively, their observations are not exactly reassuring given the enormous time and effort invested in the supposed avoidance of another banking crisis like 2008. In the US ordinary depositors were so jittery that the US Fed was clearly worried about other runs. “It appeared that contagion from SVB’s failure could be far-reaching and cause damage to the broader banking system,” the Fed’s Michael Barr, vice-chairman of supervision, told the House of Representatives. “The prospect of uninsured depositors not being able to access their funds could prompt depositors to question the overall safety and soundness of US commercial banks.”

Reckless behaviour?

As we shall see, both banks somehow slipped the leash of responsible risk-averse management that regulators imposed on them in the wake of 2008 but in the meantime the inevitable question is: have the global giants returned to the reckless behaviour that precipitated the financial crisis?

Shortly after the Credit Suisse panic, French and German authorities reportedly raided five giant banks over potential money laundering and tax evasion on behalf of wealthy clients, highly illegal activities that had brought down the wrath of regulators following the post-2008 revelations of egregious behaviour.

The question has special significance because the reforms put in place over the last 15 years were supposed to render banking shocks a thing of the past. With the Bank of International Settlements in Basle drawing up the principles and details of the reforms, national regulators had ordered a whole swathe of measures that among others separated investment from deposit banking, boosted capital ratios and liquidity, sheeted home responsibility onto specific senior executives, eliminated sky-high undeserved bonuses and, above all, ensured a tottering institution could collapse without triggering a house of cards, as happened in 2008. In short, no bank could be allowed to become ‘too big to fail.’

Simultaneously, regulators subjected the giant institutions – the systemically important institutions (G-Sibs) to much closer scrutiny that was, it should be said, often resented by the bankers themselves.

Yet in spite of all this regulation 49-year-old Silicon Valley Bank failed in just 24 hours after what the US Federal Reserve described as “a devastating and unexpected run by its uninsured depositors” while once-mighty Credit Suisse was bundled into USB, its supposed rival, with indecent haste before it failed. It turned out Swiss regulators had been worried about the viability of Credit Suisse for a while. Of these failures, Credit Suisse was by far the most disturbing.

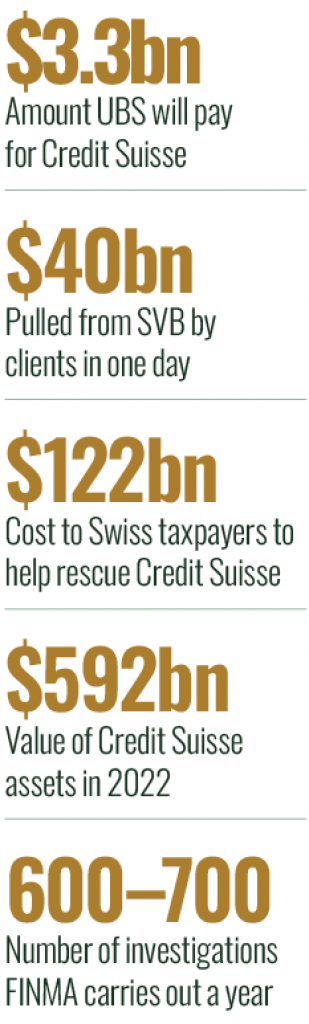

Founded in 1856 to finance Swiss railroads, it could claim 2022 revenues of nearly $17bn and assets of $592bn. It was Switzerland’s second-biggest bank and until about a year ago it had been considered impregnable. Troublesome, but still impregnable. The Swiss banking system has always prided itself on its robustness, reliability and high reputation. The main regulator FINMA is one of the most respected anywhere. Yet the Swiss government had to stump up $122bn in a hurry to underpin the rescue of Credit Suisse. That’s also against the new rules because the failure of even a G-Sib is not supposed to cost taxpayers anything.

Meantime in the US there was no question of a takeover of SVB, even at the point of a gun. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which is charged with maintaining stability and confidence in the financial system, followed the book or, as central bankers say, the ‘hierarchy.’ The FDIC quickly guaranteed all the insured deposits of SVB and Signature Bank, another federally supervised institution that went under because of a run on deposits in the wake of the general nervousness. Senior management was cleared out overnight, something the US Fed has no compunction about doing, and troubleshooting regulators moved in to sort out the mess.

Most importantly, the Fed headed off the nightmare of further runs on other banks by guaranteeing as much liquidity as they might need for up to a year. Meantime equity and other liability holders in SVB lost their investments, as the post-2008 hierarchy requires.

Speculation and repercussions

The repercussions from these failures, different though they are, are many. In the case of a genuinely global institution like Credit Suisse with activities in the US, Europe, Middle-East and elsewhere, they are of course much greater. In fact, they will run on for years. Already there is speculation about the ability of UBS, with total assets of $1.1trn and revenues of $34.6bn, to absorb its rival, partly because of the dubious nature of the latter’s assets. In theory the takeover creates an institution with $5trn in assets, but nobody is yet sure how much the assets of Credit Suisse will have to be written down.

The red ink is already spilling. The investments of Credit Suisse shareholders have taken a hit and FINMA will value its tier-one bonds at exactly nothing. Stockholders have taken a bath, also following the post-2008 rules to the letter. UBS will pay $3.3bn for Credit Suisse, a pittance compared with its pre-failure value.

So what happened that wasn’t supposed to happen? To take the US first, reading between the lines the US Fed was surprised by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Called before the House of Representatives’ Committee on Financial Services, Supervisor Barr explained that the bank was fatally wounded because of management’s failure to handle liquidity risk, which is incidentally its biggest responsibility, and that the run did the rest. Subsequent media reports say that management was focused too much on growth rather than stability and that, when internal stress tests revealed problems, they were ignored.

But why the run and why its immediate effect? It’s clear that the Fed is confused and a little shame-faced about it all. “SVB’s failure demands a thorough review of what happened including the Federal Reserve’s oversight of the bank,” said Barr. That review should become compulsory reading in the banking world because it will be a salutary lesson.

But it is already known that SVB had a concentrated business model and that its customers were mainly involved in the technology and venture capital sector, which is potentially immensely profitable but high-risk. Although the bank had been around for more than four decades, it had grown quickly in the last few years, tripling its assets in the three years up to 2022 at a time when the tech sector was booming. That should have triggered concerns. Some of the biggest failures on both sides of the Atlantic before 2008 were institutions that had grown rapidly, like Royal Bank of Scotland.

And then the pandemic intervened. To boost yield and profits, explains the Fed, SVB invested the proceeds of fast-growing deposits in longer-term securities with better rates, but it did so without having the essential expertise: “The bank did not effectively manage the interest rate risk of those securities or develop effective interest rate risk measurement tools, models, and metrics.”

Nor did the bank manage the risks inherent in its liabilities, the other side of the coin. Here senior executives fell into the classic trap – overseeing a mismatch of liabilities and assets. Or rather, some of them did. Subsequent media reports show there were serious misgivings among some staff about their boss’s decisions. The nub of SVB’s problems was that the technology sector which it served cannot normally rely on robust operating revenues and has to keep cash deposits in the bank to meet payroll and operational expenses. But those cash deposits can also be withdrawn at will and, in fact, often are.

Belatedly SVB realised it wasn’t sufficiently liquid and, on March 8, was forced to announce that it had realised a $1.8bn loss in a sale of securities but that it planned to raise capital the following week. That was a red alert to its clients and some of the smartest people in America took a close look at their bank’s balance sheet. “They did not like what they saw,” said Barr in the kind of candid assessment that is standard practice in the US.

In an alarming example of how precarious the position of a seemingly well-funded bank can be, the clients pulled more than $40bn from SVB in just one day, on March 9. Other depositors immediately followed suit and the very next day SVB failed. Within three days SVB had gone under because of the nightmare of every regulator and banker, an unstoppable run by depositors that recalled the events of the Great Crash of the 1930s when people lined up outside the doors of thousands of institutions to withdraw their cash.

Steady deterioration

While the demise of SVB is a case of incompetent management and, as the US Fed admits in so many words, supervisory failures, the story of Credit Suisse looks very much like an inept management aided and abetted by a regulator hamstrung by politicians. FINMA issued more than 100 red flags to the bank about its various failings during its steady deterioration, although the public knew nothing about them because the regulator is not permitted to release them, unlike in the US and UK.

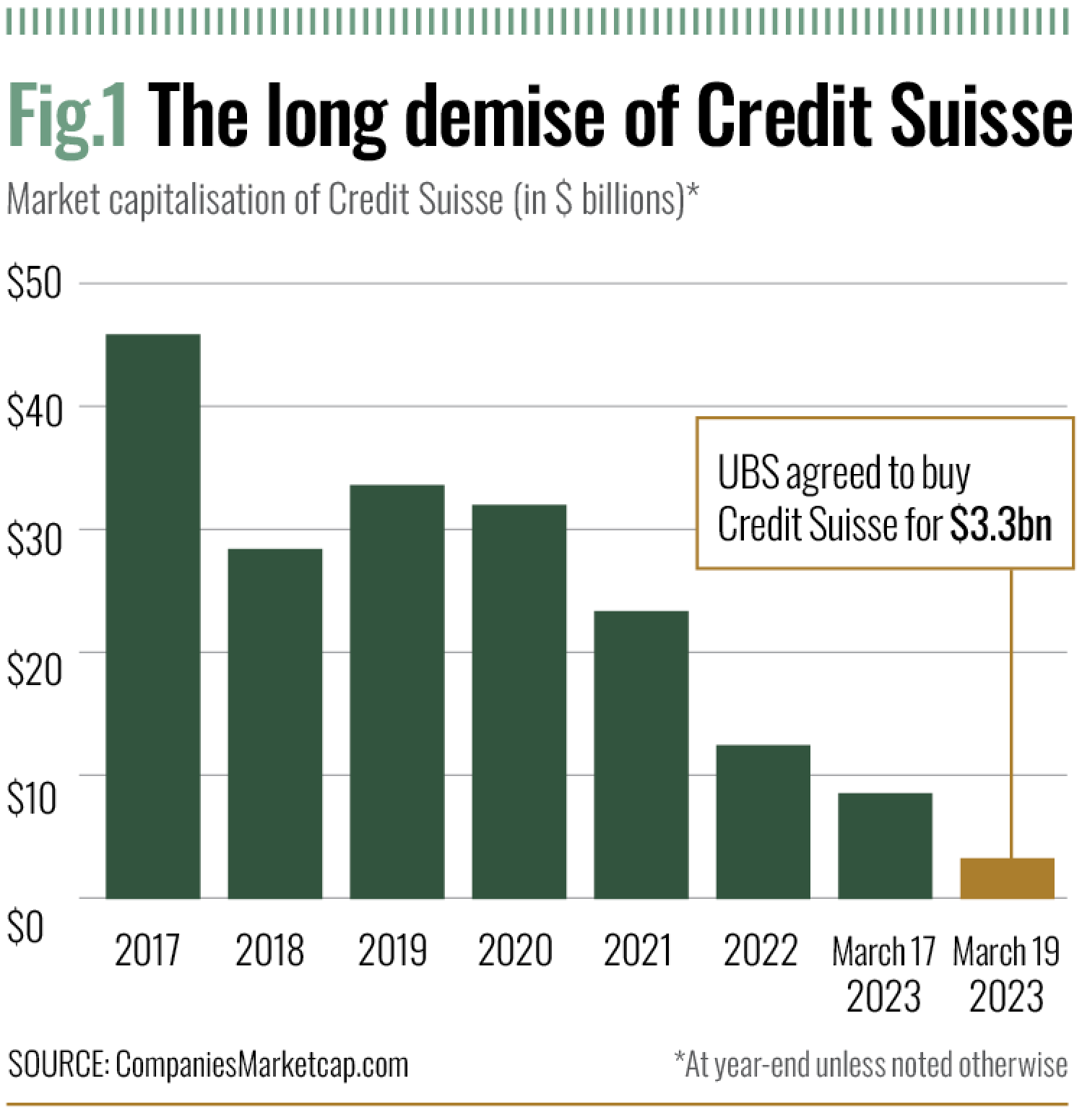

In a textbook example of how a munificently rewarded C-suite made one blunder after another, Credit Suisse was on the way down as early as 2021, largely because of $10bn in losses of client funds that had been invested in the massively indebted British supply chain financer, Greensill Capital, and $5.5bn invested in US hedge fund Archegos Capital Management.

Both failed in 2021 in an illustration of how interconnected the global finance sector is. Although several other lenders lost heavily in these collapses, Credit Suisse had taken the biggest plunge and suffered the most. These mistakes were “unacceptable,” confessed the bank’s former CEO Thomas Gottstein at the time. At the time of writing it was considered unlikely that Credit Suisse would recover much of its capital in Greensill and probably none in Archegos.

These catastrophes followed several years in which Credit Suisse plunged recklessly into investment banking, a notoriously fickle activity that had brought down US institutions in 2008 such as Lehman Brothers. Wealthy clients took fright at these huge write-downs and fled with their money, the share price declined and the bank’s credibility, surely any institution’s prime asset, collapsed. “The finger of blame points to the bank’s leadership,” concludes an analysis in Swiss Info, a publication of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation.

Events rapidly took a turn for the worse. Swiss authorities moved in a new management team in October 2022 and tried to steady the ship, principally by tidying up the troublesome investment bank business. “The bank will build on its leading wealth management and Swiss Bank franchises,” it promised in a return to its roots. FINMA approved of this spring clean – “a step in the right direction towards risk reduction,” said the chairwoman of the board, Marlene Amstead, at the time.

But it was too little much too late. In the same month the bank experienced a run on client funds of unprecedented proportions even by world standards. In the fourth quarter outflows hit the gigantic sum of nearly $155bn and, although Credit Suisse managed to scrape through once again, the writing was on the wall (see Fig 1).

Going or gone

The two events have brought to the fore the issue of ‘too big to fail’ that concerns systemically important institutions. One of the most important consequences of the reforms following the financial crisis, it’s an international standard with two parts. Either the bank is a ‘going concern’ and can be somehow rescued or it’s a ‘gone concern’ and is heading for a decent burial. Adopted around the world, the standard defines a ‘going’ bank as one that has sufficient capital to cover losses from current business while a ‘gone’ bank requires it to have sufficient capital that allows it to be restructured or liquidated.

In terms of the viability of the giant, global institutions the takeover of Credit Suisse is the first real-life test of the ‘gone’ part of ‘too big to fail.’ It is a case study that has aroused intense interest around the world and there is not a single banking authority anywhere that is not following it. So far FINMA’s Amstead believes Switzerland did the right thing in what was a collective solution involving taxpayer’s money, government, regulators and central bank, and the acquiescence of UBS.

Having helped Credit Suisse ride through earlier crises, FINMA was now faced with the even more difficult issue of how to shut it down. There were four options, she explained. The bank could be allowed to fail in what is known as ‘resolution,’ a declaration of bankruptcy with what would have been interminable legal and other issues, a temporary takeover by the state that would hopefully lead to reforms and an eventual buyer, and the forced takeover that was finally adopted.

But ultimately, there’s no escaping from the fact that Credit Suisse was not allowed to fail because of the high risk that it might trigger a financial crisis. So does that mean that the entire architecture of ‘too big to fail’ will have to be rebuilt in the light of the debacle?

Regulatory failures

Regulators always have to share some of the blame in a bank failure and, to be fair, they are usually willing to acknowledge their responsibility. In the run-up to the Great Financial Crisis, for instance, the Bank of England pursued a policy of trust in management dubbed ‘regulation-lite’ that was rapidly abandoned in the ensuing carnage.

In the case of SVB, its supervision had been moved to a new team after the bank was classified as a higher-risk ‘large and foreign banking organisation,’ a category reserved for institutions with assets of $100bn–$250bn. That’s still a few steps below the most heavily supervised category of a G-Sib, but any institution with up to a quarter trillion dollars of assets must be regarded as significant.

Almost immediately the new team became worried about the competence of management and issued a rating of ‘deficient-1’ for its enterprise-wide governance and controls. As late as November 2022, supervisors sat down with the management and warned them about emerging risks, particularly in terms of interest rates and liquidity, in which lurk some of the most recognised dangers for a bank’s overall integrity. They also expressed their concerns about the impact of rising interest rates on the financial condition of SVB as well as other banks.

But the supervisors certainly did not expect it to fail, or so fast. The relationship between banks and regulators can be a tense one. While it is important to remember that most banks abide by the rules and are anxious to comply with supervisors’ recommendations, some have to be brought to judgement. In most instances of recalcitrant banks the regulators get their way because they can unleash their big weapon – enforcement through court procedures. In Switzerland, FINMA conducts an average 40 enforcement proceedings a year, most of which never see the light of day. Apart from actual enforcement, FINMA carries out 600–700 investigations a year, which require its investigators to knock on doors the equivalent of two or three times a day “to clarify possible violations,” as FINMA puts it. Faced with the evidence, in nine out of 10 cases the bank takes corrective measures, but the big problem arises when they refuse to do so, as did Credit Suisse.

As FINMA makes clear, it is rare for institutions to defy, ignore or otherwise fail to respond to investigations and multiple rulings. Thus the case of Credit Suisse has raised an issue which Swiss authorities are debating behind closed doors. Clearly, no country can tolerate an institution that rides roughshod over the regulator and here Switzerland was unusually weak. The Bank of England, US Fed and many other central bankers have more freedom to tell it like it is, for instance by naming names. “As the events surrounding Credit Suisse show, our instruments reach their limits in extreme cases,” explains Amstead, who clearly wants to be handed more powers. “It is therefore worth considering an extension.”

But of course that’s up to the politicians and they have traditionally resisted handing FINMA the authority it needs. The authority cannot even impose a fine, something that happens routinely in France, UK and the US, among other countries. As we see, Switzerland’s politicians have shot themselves in the foot. Astonishingly, even after Credit Suisse had been tied into UBS, the country’s parliament voted after a long debate that, in so many words, it was the wrong thing to do.

Fit for purpose

On the bright side lessons are being learned. The Fed is in the middle of much soul-searching about the effectiveness and power of supervisors. Essentially, in a wide-ranging internal review it is asking whether the regulatory regime is fit for purpose. “Once risks are identified, can supervisors distinguish risks that pose a material threat to a bank’s safety and soundness? Do supervisors have the tools to mitigate threats to safety and soundness?” asks Supervisor Barr, who told the House of Representatives that “the failure of SVB illustrates the need to move forward with our work to improve the resilience of the banking system.”

In short, perhaps supervisors must get tough before it’s too late. Meantime though, the US Fed wants to apply the Basel III reforms to smaller banks like SVB, the idea being they have a bigger cushion for absorbing losses rather like the G-Sibs. And in another move that will be closely watched by the entire financial sector, the Fed plans a whole new panoply of stress tests that capture a much wider range of risks and uncovers channels for contagion. In itself, that is an admission that the current stress-testing technologies just don’t cut it.

The fear about contagion is that it is often irrational – in the modern banking system insured depositors get their money out – but fear spreads without reason. One little-known weakness in the post-2008 global banking system is the rise of fintech, the upstart sector that is determined to eat the big boys’ lunch. Nimbler, cheaper and often more customer-friendly, they have weakened the giants’ hold on the financial landscape. One result is that there are fewer banks in the US, to take just one jurisdiction. As US Fed governor Michelle Bowman explained recently, “de novo [new] bank formation has essentially stagnated for the past decade during a time when financial services have rapidly evolved.”

This matters because new banks are by definition smaller, more conservative and, surprisingly, often safer. The smallest banks often sail through a crisis while their bigger rivals struggle, explains Governor Bowman: “As we have seen over time, they often outperform larger banks during periods of stress like the pandemic and during the 2008 financial crisis.”

Also, they look after their customers better, notably small business, during hard times. If nothing else, that may precipitate a flight by depositors away from the giants. Looking ahead, current levels of bank capital probably won’t be seen as sufficient. They certainly weren’t in the run-up to the Great Financial Crisis, as regulators acknowledge, and the latest scare is prompting a rethink.

The consequences of inadequately capitalised banks run deep. For instance, the 2008 crisis with its banking failures triggered the deepest and longest recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. In America, the world’s wealthiest – and most banked – country, employment collapsed and took six years to recover; six million individuals and families lost their homes to foreclosures; and over 10 million people fell into poverty. The effects are still being felt today, as the research shows.

Although the return of the much-feared run on deposits is causing central banks concerns, on the bright side nobody is saying that the global banking sector is about to implode. “We’re in a very different place and I really don’t see this as the beginnings of a systemic financial crisis,” Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey said in a post-Credit Suisse debate.

No central banker would of course ever say anything different, but there’s no doubt that the tremors caused by the collapse of SVB and Credit Suisse have exposed cracks in the system that must now be repaired.