When it comes to manufacturing, China suffers a reputation problem. A recent survey conducted by German market research firm Statista asked consumers how high they expect the quality of products to be, based on where they were manufactured. Ranking first out of the 50 countries included in the survey was Germany. Second to last, ahead of only Iran, was China (see Fig 1).

At least according to respondents outside the country, the ‘made in China’ stamp is synonymous with cheap, poorly assembled and flimsy products. The only bright spot in the survey was that people at least associated the country with decent value for money.

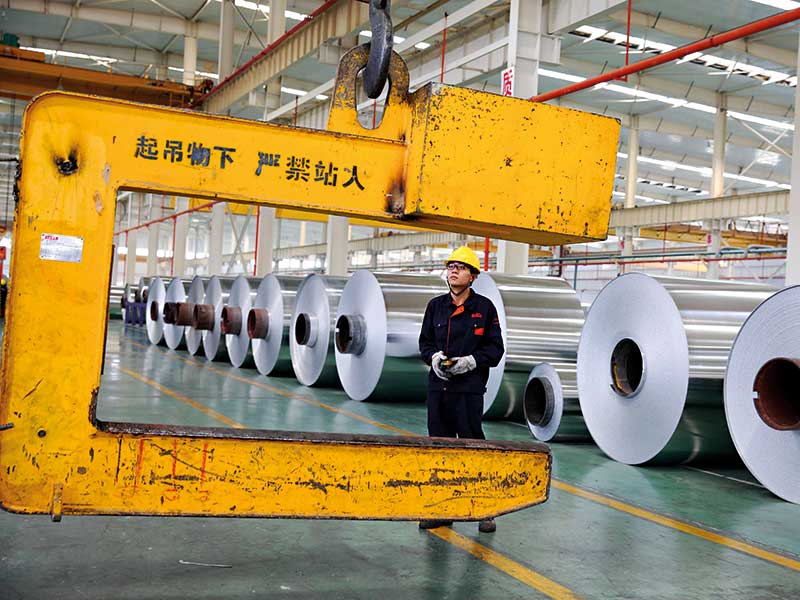

The story of China’s economic development over the past 40 years is both well documented and widely known. Thanks to low labour costs, the increasing ease of doing business globally and large amounts of state investment, China’s GDP, population and almost every other economic measurement you can think of posted overwhelming growth. However, while once regarded as the world’s factory, China can no longer maintain the level of manufacturing growth its government has become accustomed to. The particular industries it once excelled in, such as steel and concrete, are shrinking in importance when compared with the emerging fields of robotics, renewable energy and other hi-tech pursuits.

Many Chinese companies operating in these fields are dependent on parts and systems produced elsewhere. When one combines this reliance with the perception that Chinese products are simply not as good as their western counterparts, the future of China’s emerging technology sector seems bleak.

What came from this need to compete with the rest of the world was Made in China 2025, a comprehensive government plan designed to rejuvenate and reinforce the country’s hi-tech manufacturers. The programme intends to get the country to a point where it is not just a world leader in building these products, but where it is also designing and manufacturing them from the ground up.

In the two years since Made in China 2025 was announced, results of the plan have begun to emerge. However, as hi-tech manufacturers increase, international firms and bodies are growing critical of how the policy is affecting global markets. Though China’s plan is effectively still in its earliest stages, a battle for technological supremacy is emerging.

Made in China

Announced in May 2015, Made in China 2025 is designed to be a sweeping and substantial overhaul of China’s manufacturing sector. The motivation behind the initiative was a desire to help Chinese manufacturers escape rising pressure from both ends of the global market.

On the one hand, China’s low cost manufacturing sector looks set for greater competition from countries like India and the Philippines: according to Euromonitor, the average hourly wage in China’s manufacturing sector tripled between 2005 and 2016, making it far harder to compete solely on price. On the other hand, many of China’s industries lag behind their western competitors in terms of ingenuity, and are often reliant on parts designed and built overseas. Combined with the perceived lack of quality in Chinese-built products, the Chinese Government has focused on making sure the country’s products improve in quality, are more innovative, and are built using a greater proportion of locally sourced components.

Made in China 2025 also draws significant inspiration from Germany’s Industrie 4.0 and the US’ Industrial Internet strategies. The vision for the future is a manufacturing sector that is far more automated and connected through the Internet of Things than it is today. While automation in itself is not particularly new, connecting various automated manufacturing processes in a way that allows greater efficiency and lower costs is only now becoming more feasible. With this, the information and programs that underlie manufacturing processes are just as important as physical hardware. In this sense, China has a long way to go; whereas Germany averages more than 300 industrial robots per 10,000 industry employees, China only averages 19.

Once regarded as the world’s factory, China can no

longer maintain the level of manufacturing growth its government has become accustomed to

While these policies will be applied to the steel, aluminium and cement industries China has been traditionally competitive in, these sectors are gradually falling in both importance and potential for future growth compared with other sectors. To make sure China ends up designing the future as well as building it, Made in China 2025 emphasised 10 industries as particularly important priorities. These sectors include robotics, aerospace, new energy systems, electric vehicles and medical products.

Jost Wübbeke is Head of Programme Economy and Technology at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) and author of a recent report looking at the consequences Made in China 2025 may have on industrial countries. “The industries that are covered [in Made in China 2025] are mainly hi-tech industries, and the Chinese Government is saying that these will decide the future competitiveness of enterprises and countries”, Wübbeke told World Finance. “Some of these industries are not as important now as they are likely to become in the future, such as electric vehicles, wind turbines and photovoltaic systems. The Chinese Government perceives these industries as the perfect opportunity to leapfrog technologically and boost its international competitive positioning.”

Another aim is to discourage reliance on international markets. As part of the plan, the domestic content of core components and materials used in manufacturing is anticipated to grow to 40 percent by 2020, and 70 percent by 2025. It is also targeting the creation of a number of manufacturing and innovation centres. The plan has a tremendously broad scope; while the initial plan aims for 2025, extensions have resulted in even more ambitious targets set as far forwards as 2049 – the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China.

To reach these goals, the government is committing substantial funds. Two recently established funds in China – the National Investment Fund for the Advanced Manufacturing Industry and the National Integrated Circuit Fund – have received RMB 20bn ($2.9bn) and RMB 139bn ($20.1bn) respectively.

The plans in place are not just limited to direct funding from the government, but include a variety of initiatives that see state investment working in cooperation with private investment. “Their aim is indeed to build up these national champions and provide the perfect environment for them”, Wübbeke said. “You need to see it in context with other policies, which have been there before and are also running in parallel, but Made in China 2025 is indeed China’s most comprehensive strategy to upgrade its industry.”

Short-term gains

Given China’s role in the global economy and the sheer amount of money being poured into the project, the Made in China 2025 policy has the potential to transform not just the country’s economy, but the world’s business landscape. In the short term at least, there may be a significant number of opportunities for foreign companies.

In order to catch up with the rest of the world, Wübbeke said China is going to have to purchase a lot of components: “Smart manufacturing is a core component of the Made in China 2025 strategy, and it’s mostly foreign enterprises from Japan and Germany providing the smart manufacturing components and the machines behind it. So in the short term, it’s quite a big opportunity for foreign companies.”

Given China’s role in the global economy, the Made in China 2025 policy has the potential to transform the world’s business landscape

However, in the long term, the picture looks very different. With China aspiring to become both more independent from other nations’ hi-tech manufacturing fields and a leader in its own right, foreign companies could lose a customer and gain a competitor.

“It’s another matter if this strategy will turn out as intended, but the intention of the Chinese Government is to replace foreign technology”, explained Wübbeke. “To these things, Europe should not be naïve; the goals of technology substitution are obvious, and so are the instruments for implementing these goals.”

Naturally, the Made in China 2025 plan has been on the receiving end of strong criticism. In March, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China released a scathing report on the plan, describing it as a “large-scale import substitution plan aimed at nationalising key industries” that would “severely [curtail] the position of foreign business”. The report also suggested companies might be forced to hand over key technologies in order to secure near-term market access.

“The worry that we have is that this unbalanced competition landscape that we face in China might be replicated in our home turf”, Chamber President Joerg Wuttke announced before the report’s release, Reuters reported. “Are you up to it to compete against state-sponsored companies in China, as well as globally?”

Chinese officials quickly denied the suggestion foreign firms would be treated unfairly. Miao Wei, Minister of Industry and Information Technology, said at the annual plenary session of the National People’s Congress after the report was released: “Foreign and Chinese enterprises will continue to be treated equally. We have never forced foreign companies to transfer technology.” While we are still very early in the transformation strategy, international pressure to alter the plan is growing.

Product of change

China’s focus on rejuvenating its manufacturing sector represents a significant turn in the country’s export history, but is also representative of the nation’s increasingly wealthy population. Frankie Leung, a Los Angeles-based attorney and specialist in Pacific trade, said that in the past, China’s policy of trade placed an emphasis on exports in order to gain foreign currency: “But now China’s own consumers are so numerous, and the market has become very sophisticated, they are trying to change the strategy. So this is a paradigm shift.”

3x

Increase in the average hourly wage in China’s manufacturing sector between 2005 and 2016

40%

The anticipated growth of Chinese materials being used in manufacturing by 2020

300

The number of industrial robots per 10,000 manufacturing employees in Germany

19

The number of industrial robots per 10,000 manufacturing employees in China

But local consumers are not the only priority. In terms of the traditional manufacturing industry, Leung said he sees south-east Asia and Latin America – where Chinese companies are generally more highly regarded – as being significant growth opportunities. However, he added that in general he is quite cynical about the multiyear plans the Chinese Government employs: “First of all, they haven’t done enough research to understand the real economy, and secondly they don’t have the heart in it. When they show that the results do not prove what they want to achieve, they either fake data to fit the propaganda, or abandon it very fast to move on and do something else. That’s my general approach [to their policies], and I think that, with that general approach, you can understand the dynamic behind any kind of social engineering measures put out by the government.”

But despite the emphasis on smart manufacturing, the transformation of China’s economy could just as easily take a different form. “If you talk to Chinese industrial [workers], they know that the fastest growing industry is in businesses like Tencent and Alibaba”, Leung said. “They have no products, they deal with soft stuff like information; it’s very much like a service industry.” Leung said he believes many Chinese Government officials still place a greater importance on physical products than these service exports. However, this is slowly beginning to change.

Leung also believes it will be harder in the future for international service industries to compete with homegrown competitors: “Take, for example, Uber. They tried to go into China, and they gave up. They sold to Didi, the Chinese counterpart. They have a licence fee arrangement over there with the Chinese because they know that, if you really have to go into the Chinese market, to have daily contact with the consumers, foreign interests and foreign business have a very distinct disadvantage.” Leung said he believes the better tactic will be the creation of partnerships and the leasing of technology to rivals already established in China.

Still, it’s impossible to deny that China is making progress in its manufacturing sector. There is perhaps no bigger symbol of the progress China has already made towards this goal than the Comac C919, a passenger aeroplane that took to the skies for the first time in May 2017. The one-hour test flight, though small, is a chip in the armour of the Boeing/Airbus duopoly that dominates the industry. The development of a passenger aeroplane – one of the most challenging machines to build – is a significant milestone in engineering and construction for any nation.

Despite this, the flight comes with some caveats: the plane is almost certainly less capable than its competitors, and is built using a significant portion of western-made components. However, the intent of Made in China 2025 is that, in just a few years, the C919 could be built entirely from Chinese designed and manufactured parts. “We used to believe that it was better to buy than to build, better to rent than to buy”, Chinese President Xi Jinping told workers at the plant that built the C919, The New York Times reported. “We need to spend more on researching and manufacturing our own airliners.”

It seems inevitable that more Chinese companies will grow their international footprint with the support of the government, perhaps eventually becoming as well known globally as Apple, Nike or Mercedes-Benz. While many countries push against China’s growing independence, there seems to be little that could be done to stop the country continuing to develop its manufacturing sector: the stigma attached to ‘made in China’, however, may not be so easy to shake off.