How to fund the higher education of Americans is an enduring political question. There is a sense that the old system of loans and grants is no longer tenable, with mounting student debts. According to figures from the New York Federal Reserve, Americans owe $1.2trn in outstanding college loans, an increase of $78bn from just one year ago, while the cost of college has quadrupled in the past 35 years. It is of pressing concern that any US presidential candidate proposes a solution to funding the ever expanding number of prospective students and not too burdensome upon the tax-payer.

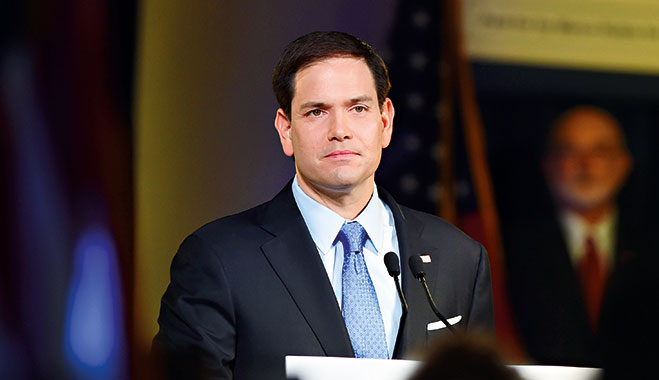

Bernie Sanders, the left-wing outsider Democrat candidate, predictably advocating a tax on the wealthy to fund college tuition – to Hillary Clinton, claiming she will try to make college as debt free as possible. Marco Rubio, generally seen as the more sensible of the smorgasbord of Republican candidates, has proposed an unorthodox idea to fund college tuition.

Certain university subjects that often do not lead to immediate or clear high paying jobs may go underfunded

Controversial plans

As Rubio outlined in a speech: “Let’s say you are a student who needs $10,000 to pay for your last year of school. Instead of taking this money out in the form of a loan, you could apply for a ‘Student Investment Plan’ from an approved and certified private investment group. In short, these investors would pay your $10,000 tuition in return for a percentage of your income for a set period of time after graduation – let’s say, for example, four percent a year for 10 years. This group would look at factors such as your major, the institution you’re attending, your record in school – and use this to make a determination about the likelihood of you finding a good job and paying them back.”

This is, however, shot through with problems. If investors are looking at students as equity, hedging for future returns on income, certain university subjects that often do not lead to immediate or clear high paying jobs may go underfunded. To the hard-nosed economist, perhaps this is a more efficient allocation of resources. Yet college is not only an economic decision, an ominous investment in ‘human capital’, but also a place where big ideas are explored and debated, even if they don’t result in any future monetary returns.

At the same time, those pursuing degrees in areas that do lead to high-paying jobs would find little benefit in the Student Investment Plan. A student expecting to earn a large salary would be reluctant to giving up such a sizeable amount – four percent according to Rubio – of their income, and would end up paying a much higher amount than their counterparts studying less profitable degrees. Indeed, in the 1970s a similar initiative was tried, with the results being that those who expected to earn higher amounts post-college not signing up to the plan.

Theory versus reality

The plan would create a complete mismatch. Those pursuing degrees in humanities subjects and not expecting to earn a high income anytime soon would not be attractive option to any investor, while the business or economics students hoping for a high paid career in finance would be. Yet for such students forsaking a future portion of their assumed high income would be far less attractive than taking on typical federal loans.

As William Deresiewicz, the author of numerous essays on US higher education noted, “Instead of individual investors investing in individual students and receiving a percentage of their individual future earnings, a better plan would involve everyone together investing in all students and receiving a percentage of their future collective earnings. Except we already have that plan: it’s called public funding of higher education – the investment part – followed by taxation of wager-earners – the return part. We just no longer invest as much as we should, which is why our return [in other words, the strength and productivity of our economy] is no longer as good as it should be.”