Top 5

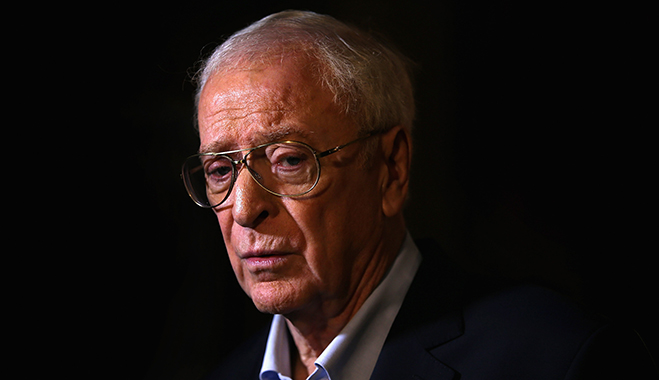

I have been a tax advisor now for 33 years. Our profession led a low-key, well-respected existence. In the last 18 months, this has changed and we have been repeatedly in the national press. The first revelations concerned the comedian, Jimmy Carr, and subsequently, such well-known names as members of Take That, Anne Robinson and Michael Caine have had their tax affairs publicised as allegedly being involved with tax avoidance schemes.

While artificial tax avoidance schemes are no longer viable for the majority, traditional tax planning has returned to the forefront. Sensible planning based on sound commercial principles is still possible to follow, while avoiding some of the serious tax pitfalls. As a result of the press attention, now tax planning is seen by many as anything from distasteful to immoral – or even worse. HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) has taken action to recoup lost tax and strengthen its armoury against companies who implement tax avoidance schemes. Some see that as a sensible reaction, while others view it as an unwarranted invasion of the rights of individuals.

Drawing the line

As far back as 1936, Lord Tomlin, in a case involving the Duke of Westminster, stated: “Every man is entitled if he can to order his affairs so that the tax…is less than it otherwise would be.” Many continue to regard this as a fundamental right. Tax avoidance – as opposed to evasion, which is a non-disclosure of income – is perfectly legal. However, the schemes which have been prevalent for the last few years have focussed on whether they should be permitted, particularly those which contain artificial elements.

Tax avoidance – as opposed to evasion, which is a non-disclosure of income – is perfectly legal

In the 1990s, a popular area of avoidance was National Insurance Contributions (NICs). Schemes were devised to pay salaries in gold bullion, platinum sponge and other commodities to take advantage of a then loophole that non-cash salary was subject to income tax but not NICs. These schemes were finally blocked by the late 1990s. However, that led to an unintended consequence. Perhaps the strangest unintended consequence I know about arose from two new experimental rules in the 1994 Caribbean Cup football tournament.

Grenada had a superior goal difference before a group match against Barbados, who needed to win by two goals to progress to the finals. However, the new rules resulted in both teams trying to score own goals in the final minutes of the match! In the tax world, the unintended consequence of solving the NIC issue was that Employee Benefit Trusts (EBT) were developed which would save not only NICs but also the income tax. A company would make payments to the trust, which would then lend the funds to the individuals. Loans are not an income so the recipients found themselves with cash, but not having suffered any form of tax. Subsequent changes to the law in 2005, 2007 and 2010 were effectively overcome by changes in the way in which EBTs were implemented, such as Employer Financed Retirement Benefits Schemes (EFRBS) taking the place of EBTs.

In another area, an unintended consequence arose when statutory tax relief for investments in British films was withdrawn in 2007. By then, some high earners had grown accustomed to deferring their income tax bills by making such investments. To satisfy their needs, new structures were developed for investments in films, computer technology, entertainment productions and media, artists and property development. The normal model has been for a client to invest cash of, say, £100,000 in an activity. The promoters would then facilitate borrowing for the client to gear this up to, say, £500,000 but the funds borrowed would never leave the control of the promoters, and would often go round in a circle to a company associated with the lender. That circularity has turned out to be a weakness when the strategies have been judged.

A short time after making the investment, accounts would be drawn up claiming a substantial loss because of the uncertain outcome of the investment or by claiming specific tax reliefs. The loss of, say, £450,000, would be available to offset “sideways” against the client’s other income. If he or she were a 40 percent taxpayer, the tax benefit would be £180,000, all for an outlay of £100,000 plus fees. Other forms of tax avoidance involve a client entering into two or more linked transactions. One is aimed at making a profit which is not taxable and another in creating a loss which can be offset sideways against another income. Taking the transactions together, there is no real loss, other than fees.

Tax avoidance has now been a vibrant ‘industry’ (as some call it) for many years, which has put a strain on the Exchequer. The Times reported that one tax scheme called Liberty attracted £1.2bn of sheltered income until it was stopped in 2008. Another scheme promoter, Icebreaker, allegedly attracted over £300m. OneE Tax was so successful that it appeared in the fast track lists in The Sunday Times in 2011 and 2012 as one of the 100 fastest-growing private companies in the UK. Taxpayers have grown used to the idea that they needn’t pay all the tax otherwise due. Their accountants and/or solicitors have received substantial referral commissions. The scheme providers and their barristers and other advisers have made large amounts of fee income.

Changes to the system

In the meantime, HMRC has dragged its feet over taking these schemes to the tribunal. It has been aware of them for several years because of the need for promoters to disclose them under the Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Schemes (DoTAS) rules. After disclosure however, all that HMRC has done in most cases is to issue standard letters asking for information and then leave it.

It can take HMRC three years or more before it starts a dialogue to consider the technical merits of a scheme. It normally takes six years or more to take a test case to the tribunal. During that period, the taxpayer will hold on to the funds he has saved by not paying the tax. Tax is only payable if and when HMRC win an appeal at the tribunal and, even then, there can be further deferral by appeals in the courts.

So what has changed? First, in 2013 a general anti-abuse rule was brought onto the statute books. This aims to counter tax schemes, which are seen to be against the intention of the law even if they have circumvented it in some way. It is early days yet, but I am not aware of any occasion where that rule has been invoked. This year, HMRC have been given a new weapon to issue notices to taxpayers who have been involved with a wide variety of schemes, demanding payment of the tax saved – irrespective of the technical merits of the schemes.

However, there is no mechanism for any independent appeal against the notices. When any of our clients receives one, we will commence a dialogue with HMRC to bring the outstanding issues to a head. If this is not done and HMRC has its hands on the tax, they will have no incentive to bring the case to the tribunal. We can also consider all the circumstances leading to a client implementing a scheme, including whether it might have been mis-sold.

On a separate tack, HMRC has been successful with some test cases before the tribunal. It has notched up four straight wins against schemes devised by one firm, NT Advisers. It has also won two tribunal cases against Icebreaker. Liberty will be before the tribunal in 2015. However, it is not all doom and gloom for taxpayers. HMRC have lost cases involving tax schemes against Glasgow Rangers, UBS and Deutsche Bank.

Taking all the negatives into account, anyone implementing tax avoidance schemes now will need to take risks and not be averse to the lengthy legal process. It needs to be remembered that HMRC will probably seek payment of the tax avoided up front. The taxpayer will then not have saved anything and will be due to pay fees in the hope that the scheme will be judged to be successful, in which case a tax repayment will then be due, but that is unlikely to be for many years.

It also needs to be considered that, more often than not, the judiciary is now sympathetic to HMRC and will look to find reasons to defeat schemes that are artificial. Very broadly, if a tax-geared plan involves artificial and/or un-commercial steps, then they will look at it very carefully and, at best, the outcome will be uncertain and probably expensive to obtain. For these reasons, such schemes are unlikely to have any mass appeal moving forward.

For further information visit mitaxpartners.com